|

The asrai is a type of English water fairy. This species appears in a few fairytale collections and fantasy novels, but they were first popularized by Ruth Tongue's 1970 book, Forgotten Folk Tales of the English Counties.

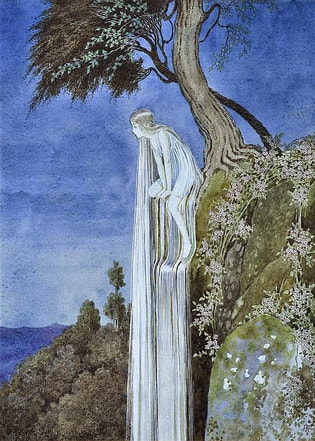

Tongue has been described as problematic. Although she's obscure today, her work inspired later authors and has found its way into all sorts of media. She was an amazing storyteller, and she was writing down traditions that had never been recorded before. Here's the problematic part: she made them up. She often built upon scraps of genuine folklore, but the greater part of her work is original. So where does this leave the asrai? In the tale that Tongue recalled from Shropshire and Cheshire, Asrai are peaceful fairy folk. Living deep beneath lakes, they emerge to see the moonlight once every hundred years. They will die if they ever come near sunlight. One night, a fisherman out in his boat happens to catch an Asrai in his net. He is entranced by her beauty and decides to take her home, even though she weeps and protests in a strange language. He covers her with some wet rushes. In the process, she touches his hand, leaving it icy cold for the rest of his life. He rows back as quickly as he can and reaches the shore just as the sun rises. When he picks up the rushes, he finds that the Asrai has melted away to nothing. Okay, so first off, for this book, Tongue had lost most of her notes in fires or moves and had to recreate the stories from memory. Whoops. Still, she manages to give two versions of this story. The first comes from "the Whitchurch Collection (Shropshire)." I found one Whitchurch Collection at the Whitchurch Heritage Center, but it dates from 2008. There's no way to tell what collection Tongue meant or where it might be now - let alone what was in the collection. For the second version, which is exactly the same with some different wording, Tongue says "From the author’s recollections of an account in local papers published between 1875 and 1912.” That is thirty-seven years' worth of newspapers. THIRTY-SEVEN YEARS. To accompany the tale, she provides quite a few anecdotes - a Welsh maid who calls full moons "Asrai nights," and various people who avoid deep water because of asrais. Again, her attributions are fragmentary and vague. One says simply "Correspondence, 13 September 1965 (destroyed by fire)." Going through English and Welsh tales, I found several stories of captured mermaids, but nothing about water fairies that melt. One water creature in Shropshire lore is the monstrous Jenny Greenteeth, but she couldn't be more different from the asrai. (Edit to add: Tongue's tale feels closer to the widespread English and Welsh tales where men take lake-dwelling fairies as brides, only to break some taboo and cause their wives to return to the water forever. Still, it remains unsettlingly unique.) There are plenty of spelling variants: asrey, ashray, azurai, and more. I searched the English Dialect Dictionary, the Oxford English Dictionary, and several books of dialects. The only word I found that was even somewhat close is askal, a water animal or newt, also spelled asker or asgill. Incidentally, Tongue's notes mention a person who thought "asrai" was a term for a newt. As of writing this, I am stumped. Every modern mention of the asrai goes back to Tongue. I have found one person's account of asrai that predates her book - in the works of Robert Buchanan. Buchanan published his poem "The Asrai" in The Saint Pauls Magazine, April, 1872. The brief verses described an ethereal race called the Asrai, "pale, yet fair" immortal beings living in darkness before the creation of sunlight. They are innocent and gentle, lacking human passions and pleasures, but also human vices. In 1875, the author R. E. Francillon wrote to Buchanan and asked him to submit a poem for Francillon's novel Streaked with Gold. The novel was to be published anonymously in the special 1875 Christmas issue of The Gentleman's Magazine, although the authors' identities were an open secret. Buchanan responded with "The Changeling: A Legend of the Moonlight." This poem, included as Chapter VI, has nothing to do with the rest of the book. It begins with a few verses very similar to its predecessor, explaining the Asrai, who are "cold . . . as the pale moonbeam." After the arrival of the sun, "the pallid Asrai faded away," going almost extinct, with only a few surviving in mountains and lakes. In their place, humanity begins to thrive. One Asrai mother envies the humans and wishes that her baby could live as one of them and gain his own soul. She leaves her home beneath the lake that night and enters a human house, where a woman and her newborn have just died in childbirth. The Asrai's spell causes her baby to inhabit the dead child's body, making him the titular Changeling. He grows up as a mortal man, while his mother invisibly watches over him. However, the human world corrupts him and he becomes cruel, lustful and violent. He eventually repents. Now an old man, he is known as the Abbot Paul and lives in a monastery by the lake where he was born. One night, his mother rises from the water and calls him. He dies and leaves his mortal form behind, freeing his Asrai self, but he has earned a soul and must move on to the afterlife. Mother and son are separated forever. I have no resources on what inspired Buchanan, except for a later mention of the poem by R. E. Francillon. In their correspondence, Buchanan provided the only clue to his inspirations by mentioning "the Bala Lake Tradition." There are a few stories about Lake Bala or Llyn Tegid in Wales, although I'm not sure which Buchanan meant. There is supposed to be a sunken city beneath its waters, and you can sometimes hear sounds or see its lights deep within. "The Changeling" also includes familiar motifs like the water fairy who lacks a soul. Tongue's asrai have webbed hands and feet and green hair. They are the size of twelve-year-old children. Buchanan's Asrai are pale, dressed in snowy white. They are invisible to humans, and seem more like spirits than mermaids. They don't melt. However, both are associated with moonlight and cold, live underwater, and avoid sunlight. They're also both associated with Wales and the Welsh border. Tongue's friend, the famous folklorist K. M. Briggs, took Buchanan's poems as evidence of an older tradition. However, although some elements of his poetry were inspired by fairytales, I have found no evidence that Buchanan ever said the asrai themselves were from folklore. It even seems like he developed the asrai between the first and second poems, since they have more ties to folklore in "The Changeling." Some of Tongue's stories do have a basis in tradition, but here, it's unclear. Her sources are impossible to track down. She throws out a few names, a few hints at newspaper articles and collections, but on closer inspection, they melt away just like the asrai. It's very easy to imagine her reading a book of poems and later remembering a few romantic details: delicate water sprites, greedy humans, a tragic ending. The asrai's haunting story catches the imagination. Almost fifty years after the publication of Forgotten Folk Tales, it's continually told and retold by different authors. A 2009 family event in Shropshire had a storytime segment featuring "north Shropshire’s very own mermaids, the Azrai." The asrai may not have been part of folklore before Ruth Tongue. Still, they're definitely part of folklore now. Update 6/7/2020: A fun little note - although Buchanan remains the oldest and only source for asrai, I have discovered an older story with a plot similar to Tongue's asrai tale. This tale comes from France. La Dame de la Font-Chancela was an otherworldly woman who would appear on moonlit nights by a fountain called Chancela. A local lord, seeing her beauty, snatched her up and tried to ride away with her on his horse. Instantly, she vanished from his arms, leaving him with a frozen feeling that put a stop to any lovemaking for more than a year. (Laisnel de la Salle, Croyances et Legendes du Centre de la France, 1875, p. 118) Update 1/1/24: Hey! Since this blog post, my essay "Melting in the Daylight: The Asrai’s emergence in modern myth" has appeared in Shima Journal. Read that essay for additional research and better context on the asrai mythos, including some must-read quotes from Robert Williams Buchanan's co-writer. Sources

3 Comments

I always heard the stories where King Arthur was taken to Avalon after his death, and was supposed to sleep until England needed him. However, there are also stories where he's still hanging around as a bird - either a raven or a chough. Choughs are recognizable by their red beaks and legs.

The tradition was mentioned as early as in Don Quixote. The first detailed examination was the 1903 book Popular Romances of the West of England. In this was gathered traditions of Arthur appearing as a raven, crow, or chough, particularly in Cornwall. There's a really good rundown of all this at "'But Arthur's Grave is Nowhere Seen': Twelfth-Century and Later Solutions to Arthur's Current Whereabouts." I first stumbled across this Arthurian tidbit in a story about a pixie who loses his laugh and regains it with the help of the chough King Arthur. You can find this tale as "The Adventures of a Piskey in Search of his Laugh" in North Cornwall Fairies and Legends by Enys Tregarthen (1906), or "The Pisky Who Lost His Laugh" in Traditional Cornish Stories and Rhymes. by Donald R. Raw (1971). "Nya-Nya Bulembu or the Moss-Green Princess" is a tale from Swaziland. I first found this story summarized in the picture book Finding Fairies: Secrets for Attracting Little People From Around the World. The story was intriguing, and I tracked down the original version in the 1908 book Fairy Tales from South Africa.

In the 1908 version, there is a Chief with two wives and a daughter by each one. He loves one daughter, Mapindane, and despises the other, Kitila. Wanting to humiliate Kitila, the chief has his hunters go out seeking a monster called the Nya-nya Bulembu, a hideous beast with a moss green hide. He sends his huntsmen to find such a creature. They find one living in a blue pool, but when they summon it with a chant, it turns out to be old and toothless with no moss on its hide. The second is equally unimpressive. Finally, they find a suitably terrifying beast in a green pool. They bring it home and skin it. When Kitila is wrapped in the skin, she cannot remove it and becomes indistinguishable from a normal Bulembu. She is left to live as a servant, abhorred by everyone for her monstrous appearance. However, one day she meets a fairy man who takes pity on her and gives her a carved stick. From then on, whenever she goes to bathe in the river, she is joined by the fairies, her monstrous skin comes off, and she becomes beautiful again for a little while. One day, a visiting prince sees her bathing and is stricken by her beauty. Even though she becomes hideous again when she leaves the water, he takes her as his wife. When she goes to bathe on the morning of their wedding, her Bulembu skin is finally stripped off once and for all. The couple lives happily ever after. The book is verrry dated. Although the foreword says that the tales are traditional, I was unsure whether I would find other versions of it. It turns out that Nyanyabulembu (plural dinyanyabulembu) is a Setswana word which translates as dragon. I also found the story "A Boy Goes After a Nyanyabulembu," performed by Sarah Dlamini, in the book The Uncoiling Python: South African Storyteller and Resistance. In this story, a king wants a Nyanyabulembu skin to make a coat for his child - not as a curse, but as a sign that this child is beloved and will one day be the next king. Only one boy is brave enough to go hunting the monster. Just like the huntsmen in the first story, he visits two blue pools, where he summons the monster with a short chant, but finds it unimpressive. At a third, green pool, he finds a strong, healthy monster. It chases him, and at the end of the chase the monster is killed, the boy is greatly rewarded, and the monster's skin is turned into a ceremonial cloak for the next king. In some places, there are parallels - most notably, the repetition of finding the monster in its pool and trying to find one suitably frightening. However, the intent of the hunt and the creation of the Nyanyabulembu cloak is completely different. One story is reminiscent of Cinderella and Beauty and the Beast. The other is the tale of a young man coming of age. EDIT 7/2/2018: I've found another version of the story! "The Ogre Scaly-Heart" (Nwambilutimhokora) features a beautiful young bride who, en route to her wedding, is forced to switch places with an ogre and wear a hideous monster skin. When she's alone, she takes off the skin and bathes in the river, and is joined by the ghosts of her relatives and servants. The truth is revealed when a child sees her and tells the intended husband. (The life of a South African tribe, vol 2, by Henri A. Junod.) And even more variants exist:

Sources

Pixar's next short, accompanying Incredibles II, looks like it'll bear some resemblances to the story of the Gingerbread Man. In this story, it's a dumpling that comes to life.

The Entertainment Weekly article |

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed