|

The Three Little Pigs is one of the most iconic fairytales, instantly recognizable in any list. But where did it come from? In fact, the earliest known version of the story actually features not pigs, but pixies.

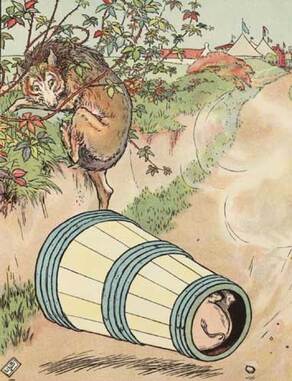

This story, Aarne-Thompson-Uther Type 124, resembles tales like "The Wolf and the Seven Young Kids" (ATU 123) and "Little Red Riding Hood" (ATU 333) where a predator tries to gain access to its prey's home through trickery or force. The listener identifies with a child like Red Riding Hood, or a domesticated animal like the goats or pigs. Sometimes the victim escapes with a clever trick. In other versions, he or she is gobbled up whole, and may or may not escape the wolf's belly. However, the three pigs are sort of latecomers. In 1853, an untitled story about a fox stalking a group of pixies was published in English forests and forest trees, historical, legendary, and descriptive. The story was also recorded in “The Folk-Lore of Devonshire” in Fraser's Magazine vol. 8 (1873). The pixies in the fox story live in an oddly domestic colony; two who dwell in wooden and stone houses are eaten. The fox, in search of prey, knocks at each door and calls "Let me in, let me in" before breaking the house open. However, a clever third pixie lives in an iron house which the fox can't break into. At the end, the fox finally captures the pixy in a box. However, the pixy uses a magical charm to trick him into switching places, and the fox dies. This is the earliest known version of the story. So how did we get to pigs? [Edit 3/23/21: J. F. Campbell's Popular Tales of the West Highlands, first published around 1860, mentions the pig story. "There is a long and tragic story which has been current amongst at least three generations of my own family regarding a lot of little pigs who had a wise mother, who told them where they were to build their houses, and how, so as to avoid the fox. Some of the little pigs would not follow their mother's counsel, and built houses of leaves, and the fox got in and said, "I will gallop, and I'll trample, and I'll knock down your house," and he ate the foolish, little, proud pigs; but the youngest was a wise little pig, and, after many adventures, she put an end to the wicked fox when she was almost vanquished, bidding him look into the caldron to see if the dinner was ready, and then tilting him in headforemost."] In 1877, Lippincott's Monthly Magazine featured William Owens' article "Folk-Lore of the Southern Negroes," including the story of "Tiny Pig." Seven pigs are hunted by a fox, who goes to each of their houses and asks entrance. The pigs each reply in rhyme, "No, no, Mr. Fox, by the beard on my chin! You may say what you will, but I'll not let you in." The fox proceeds to blow down each house and eat the occupant. Only the seventh one, Tiny Pig, has built a strong stone house, and the fox finds that he cannot blow it or tear it down. The fox attempts to enter through the chimney, but Tiny Pig has a fire waiting for him. In an odd note, Owens compares "Tiny Pig" to an Anglo-Saxon tale called "The Three Blue Pigs." He implies that this was the source for the African-American tale. He gives no source for this story, but it seems he expected his readers to recognize it. However, Thomas Frederick Crane, a collector of Italian tales, seemed baffled by the reference and wrote that he was unable to find the tale. The tale seems to have been strongly present in African-American folklore of the time. In addition to this appearance in Lippincott's Magazine, Nights with Uncle Remus: Myths and Legends of the Old Plantation by Joel Chandler Harris (1883) featured "The Story of the Pigs." Five build houses for themselves from "bresh," sticks, mud, planks, and rock. Brer Wolf sweet-talks and lures each one, coaxing them to open the doors of their respective homes. In this way, he devours them one by one. Only the Runt sees through his deception. In a scene reminiscent of both Red Riding Hood's dialogue with a disguised wolf, and the Seven Kids' protests that the wolf doesn't resemble their mother, Runt sees through each of Brer Wolf's claims that he's one of her siblings. Again, there is the ending with the chimney and the pig's waiting fire. A Harris story published later, "The Awful Fate of Mr. Wolf," told a similar narrative with Brer Rabbit as the protagonist. "The Three Goslings" appeared in Thomas Frederick Crane's Italian Popular Tales in 1885. This is another close variation on the story, but with geese rather than pigs. Here we find the wolf blowing down houses. Ultimately, the third gosling pours boiling water into the wolf's mouth to kill him, and then cuts open his stomach to free her sisters. (I'm not sure why the boiling water didn't hurt them.) Crane collected this from Tradizioni popolari veneziane raccolte by Dom. Giuseppe Bernoni, vol. 3 (c. 1875-77). He also included a story called "The Cock," which similarly featured a wolf blowing down animals' houses (in this case built of feathers). Our modern famous trio of pigs can be traced back to James Orchard Halliwell's Nursery Rhymes of England (1886). The tale was titled "The Story of the Three Little Pigs." Here is the final pig living in a brick house. Here are the rhyming couplets with the wolf calling out, "Little pig, little pig, let me come in" and huffing and puffing houses in. A few scenes, such as the wolf trying to lure out the pig and the pig duping him, are identical to scenes in the pixie story. As in the Italian stories, the wolf blows down the houses, and as in the African-American versions, the ending has the wolf's descent through the chimney. (However, the pig boils him and eats him, reminding one of the Italian gosling's boiling pot of water.) The British version featuring the pigs gained popularity through Joseph Jacobs' English Fairy Tales (1890), which cited Halliwell. Another version showed up in Andrew Lang's Green Fairy Book (1906). Some African and Middle-Eastern versions tell the same story with different animals, such as sheep or goats. In some areas, human main characters seem more popular, as in the Moroccan tale of Nciç (Scellés-Millie, Paraboles et contes d’Afrique du Nord, 1982). A sultan and his seven sons travel to Mecca, but one by one the sons lose courage and build houses - one with walls of honey, another with walls of date paste. The seventh and smallest son Nciç builds an iron house and faces off against a ghoul. The story of the fox and the pixies remains an outlier. It is the first known tale to introduce the now-familiar framework of the Three Little Pigs. However, it is also oddly rare. Pigs, fowl, goats, and humans all star in similar tales, but I've never encountered another version with pixies. And what exactly makes foxes a natural enemy of pixies? The 1873 article in Fraser's Magazine remarks that "There is a very curious connection between the pixies and the wild animals of the moor, especially with the fox, which features in many local stories. These turn frequently on a struggle in craft and cunning between the fox and the pixie." However, the only story cited is this one - not exactly a large sample size - and the author admits that the story of the pixies living in individual houses of iron, etc., is atypical. Meanwhile, in the other stories recorded in English Forests, pixies are "merry wicked sprites" who torment horses, lead humans astray in the woods, and steal babies. These are not cute winged fairies. They appear as "large bundles of rags," or occasionally tiny sprites dressed in filthy rags. Rather than being harmed by iron like some folkloric fae, they are miners and metalworkers. In one story, they are apparently immune to gunfire ("they were not to be harmed by weapon of 'middle earth'"). In the fox story, however, they are hapless creatures easily devoured by a woodland animal. The only pixy-ish thing they do is at the very end, when the final survivor uses an unspecified "charm" to entrap the fox. I believe the answer is lies in a confusion between similar words. The word "pixy" is close to "pig" - and that's before you get into related words like puck or pug. One variation is pigsies or pigseys. Pigsie is a Devonshire term for pixie. The story of the fox and the pixies is from Dartmoor, in Devon. The pixie version could have arisen through a misinterpretation of the animal pig (or piggie) as the supernatural creature pigsie. If it was originally about pigs, that would explain why similar tales frequently feature animal heroes, and the same tale was widespread with pig protagonists even on the other side of an ocean. It would also explain why the Dartmoor tale's pixies act so unpixylike and helpless, with only one mention of magic thrown in at the end almost as an afterthought. I can only think of a couple of versions of The Three Little Pigs which feature fairies as protagonists, and they are modern take-offs. In 1996, a book titled Feminist Fairy Tales by Barbara Walker featured a parody of the Three Little Pigs as "The Three Little Pinks." In this fable about girl power, a misogynistic gardener named Wolf comes at odds with three flower fairies who share the task of painting flowers pink. I found this parody less than impressive. But it's still intriguing in how it cycles - perhaps unknowingly - back to one of the earliest published versions of the tale. Oh, and there was an early 20th century version of "The Wolf and the Seven Young Kids" which featured a goblin and seven little breeze spirits. That was "The Gradual Fairy" by Alice Brown, published in 1911. I do wonder about the "Three Blue Pigs" tale mentioned by William Owens, which could potentially date back before the tale of the fox and the pixies. Perhaps it didn't survive. That would be a fascinating find, though. SOURCES

4 Comments

|

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed