|

You may have heard of Tom Thumb and Thumbelina, but have you ever heard of Svend Tomling?

Svend Tomling is the third oldest surviving thumbling tale, and is largely forgotten other than a few footnotes. Interestingly, its more famous predecessors, the Japanese Issun-Boshi and English Tom Thumb, are both fairly unique among thumbling tales. Issun-Boshi is one of the short stories and fairytales known as the Otogizōshi, written down mostly in the Muromachi period from 1392-1573. The exact date of Issun-Boshi's origin is unclear, but it's usually assigned to the 15th or 16th century. Japanese thumbling tales make up a unique subtype, with similarities to The Frog Prince. "Issun-boshi" is a romance in which a tiny, unassuming hero wins a princess for his bride, and then transforms into a handsome prince. The story still contains classic Thumbling motifs, and the story is surprisingly close to that of Tom Thumb all the way over in England. Issun-Boshi is born to an elderly couple who pray for a son; he uses a needle for a sword; he leaves home to serve an important nobleman. An oni, or demon, tries to swallow him, but Issun-Boshi escapes from his mouth alive. Tom Thumb is also of unclear original date, but at least we have dates for some important pieces of evidence. His name is mentioned in literature as early as 1579. A prose telling of the tale was printed in 1621, and a version in verse in 1630, although these are dated to the printing of the individual copy, not to the date of composition. The prose and metrical versions are very different, but hit most of the same beats. A childless couple turns to the wizard Merlin for help. Their son, who is born unusually quickly and of tiny size, wields a needle for a sword. He is swallowed in a mouthful of grass by a grazing cow, cries out from its belly, and is excreted. A giant tries to devour him. He is swallowed by a fish and discovered when someone catches it to cook it. He goes on to serve in King Arthur's court, then falls sick. Here the two editions diverge - the metrical version has him die of his illness and be grieved by the court, but the prose version has him recover when treated by the Pygmy King's personal physician, and go on to have other adventures including fighting fellow literary character Garagantua. Both of these stories are clearly thumbling stories, but they do not fit the usual map of Aarne-Thompson Type 700, a formulaic tale found consistently through Europe, Asia, the Middle East and North Africa. The Grimms were aware of this formula and actually published two thumbling stories. Their first was Thumbling's Travels, also a rather unusual example, but they later went back and added Daumesdick (Thumbthick, also translated as Thumbling), which better fit the pattern. A childless couple wishes for a son; he is only a thumb tall; he drives the plow by riding in the horse's ear, is sold as an oddity, escapes, has an encounter with robbers, is swallowed by animals, and finally returns home. Issun-Boshi, again, is part of a unique subtype. As for Tom Thumb, it's likely the subject of some literary embellishment, expanding a simpler traditional tale. Hints of the wider tradition peek through, like a scene where Tom returns home with a single penny and is welcomed by his parents. This is where many Type 700 stories end, but Tom Thumb instead keeps going. The traditional tale started really getting attention with the Grimms, but they were not the first ones to publish an example. The earliest surviving specimen is the Danish "Svend Tomling", or Svend Thumbling. Svend is a common men's name meaning "young man" or "young warrior," giving it the same generic feel as "Tom" in English. Both Svend Tomling and Tom Thumb essentially boil down to the same name of "Man Thumb," the way the name Jack Frost boils down to "Man Frost." Svend Tomling appears to have been the generic name for a thumbling in Denmark; it was also used for a Hop o' My Thumb type, which is an entirely different tale. The relevant version is a 1776 booklet by Hans Holck. It drew attention from the Danish historian Rasmus Nyerup, and from the Brothers Grimm. Nyerup, in particular, remembered reading or hearing the story as a child. The translation I've been working on is admittedly choppy, and I take responsibility if it's in error. "Svend Tomling" begins, as most thumbling stories do, with a childless couple. The wife goes to visit an enchantress and, upon instruction, eats two flowers. She then gives birth to Svend Tomling, who is born already clothed and carrying a sword. The section that follows is almost exactly the classic thumbling tale, with some unique details. Svend helps out on the farm by driving the plow, sitting in the horse's ear. A wealthy man witnesses this, purchases him from his parents, and carries Svend away (specifically, keeping him in his snuffbox). Svend escapes. Falling off their wagon, he lands on a pig's back and begins riding it like a horse. However, he is attacked by wild animals, and eventually the pig runs away. Lost in the middle of nowhere, Svend overhears two men plotting to rob the local deacon's house and asks to come along. He makes so much noise that he awakens the servants, and the thieves flee. There is a small divergence here, where the house owners think that Svend is a nisse (a Danish house spirit similar to the brownie) and leave out porridge for him. It doesn't take long before Svend is accidentally swallowed by a cow eating her hay. He calls out from inside her stomach to the milkmaid, who is frightened and thinks the cow is bewitched. Here's another divergence: people take this to mean that the cow can foretell the future, and flood to visit. This introduces a long monologue from a priest complaining about the peasants. Ultimately the cow is slaughtered. A sow eats the stomach in which Svend is still trapped, then poops him out. He falls into the water, where his own father happens to hear him crying out for help, and takes him home to recover. So far the plotline has been generally typical, but at this point, the story strikes out in its own direction. Svend announces that he wishes to take a wife. In particular, he wants to marry a woman three ells and three quarters tall. The length of an ell varied by country, but in Denmark, it was considered 25 inches. Svend Tomling is speaking of a wife who would be something like seven feet tall. His parents try to dissuade him, saying that he's far too small, and Svend grows frustrated. He begins bothering a "Troldqvinden" (a troll woman or witch) until she gets angry and transforms him into a goat. His horrified parents beg her to have mercy, and she relents and changes him into a well-grown man. The rest of the booklet (four pages out of the whole sixteen!) deals with Svend and his parents discussing his future, with questions of choosing an occupation and a bride, as he sets off into the world. Rasmus Nyerup took a pretty dim view of this story, remarking that great liberties had been taken with the folktale he remembered - particularly the priest's long speech about the problems with peasants, which has nothing to do with Svend Tomling. I suspect that the disproportionately long section on life advice is also original. The motif of eating two flowers and then giving birth to an unusual child is striking. This is exactly what happens in the story of King Lindworm (also Danish), where the resulting child is a lindworm and must be disenchanted. Also in Tatterhood (Norwegian), the queen who eats two flowers gives birth to a daughter, just as precocious as Svend, who rides out of the womb on a goat and carrying a spoon. Tom Thumb is usually listed as an influence on Hans Christian Andersen's Thumbelina. However, I think Svend Tomling might have been a stronger influence. If Rasmus Nyerup heard the story as a child, Andersen might have too. Both Svend Tomling and Thumbelina begin with a childless woman visiting a witch for help. Svend's mother eating flowers to conceive hearkens to Thumbelina being born from a flower. Both Svend and Thumbelina focus on the question of the character finding a fitting mate and a society that they fit into. Svend, like Thumbelina, is faced with incompatible mates, although for him these are ordinary human women, and for her, talking animals. Ultimately, otherworldly intervention transforms them to fit into their preferred society. Svend goes to a troll woman who makes him tall enough to seek a bride, while Thumbelina marries a flower fairy prince and gains wings like his. (Actually, Issun-Boshi did this too, getting a magical hammer from an oni and growing to average height.) Overall, Thumbelina has more in common with Svend Tomling and even Issun-Boshi than she does with Tom Thumb. The story itself is not all that great, but it does provide one of our earliest examples of the Thumbling story - and casts light on the others that followed. Sources

1 Comment

There's a lot of overlap between witches and fairies in older folklore, and the idea of a witch's voyage in an unusual vessel was a common one. According to A Discoverie of Witchcraft (1584), witches like to "saile in an egge shell, a cockle or muscle shell, through and under the tempestuous seas."

All throughout Europe ran the superstition that people should never leave eggshells unbroken. This is mentioned as early as the writings of Pliny the Elder: "There is no one, too, who does not dread being spell-bound by means of evil imprecations; and hence the practice, after eating eggs or snails, of immediately breaking the shells, or piercing them with the spoons." This suggests sympathetic magic, the possibility that someone might use something connected to you to curse you. In 1658, Sir Thomas Browne said that this custom was to prevent witches who might "draw or prick their names therein, and veneficiously mischief their persons." There were many superstitions of eggs being unlucky. Breaking eggshells over a child would deter witchcraft. Strings of blown eggshells were unlucky when hung inside a house. (Signs, Omens and Superstitions, 1918) Any egg taken aboard a ship would cause contrary winds, and some fishermen would not even call them by name, but referred to them as "roundabouts." The relevant thing here is the superstition that eggshells were witches' boats. This was all throughout Europe. Eggshells had to be crushed or poked full of holes, or otherwise either witches or fairies would set to sea in them and wreck ships. Along the same lines, a witch named Mother Gabley drowned sailors "by the boiling or rather labouring of certayn Eggs in a payle full of colde water." This could have been sympathetic magic, "raising a storm at sea by simulating one in a pail." (Folklore vol. 13, pg. 431). Another suggestion put forth in an issue of Notes and Queries was that "witches could use them, if whole, as boats in which to cross running streams." This could connect to the tradition that evil entities like vampires cannot cross running water. Eggshells were also for fairies, as I mentioned in a previous post. In the 1621 chapbook "The History of Tom Thumb," Tom brags that he can "saile in an egge-shel." According to Lady Wilde's Superstitions of Ireland (1887), "egg-shells are favourite retreats of the fairies, therefore the judicious eater should always break the shell after use, to prevent the fairy sprite from taking up his lodgment therein." In the Netherlands, it was said that when eggshells floated on the water, the alven or elves were riding in them. (Thorpe, Northern Mythology vol. 3. 1852.) In Russia, the smallest rusalki do the same thing (Songs of the Russian People.) Apparently these eggshell boats weren't confined to watery voyages, but could cross land too. In 1673, a teenaged girl named Anne Armstrong gave testimony accusing several women of witchcraft. She described one of them arriving at coven meetings "rideing upon wooden dishes and egg-shells, both in the rideinge house and in the close adjoyninge." (Publications of the Surtees Society, vol. 42) Back to Discoverie of Witchcraft - witches weren't just supposed to use eggshells, but cockleshells and sieves. In Cambrian Superstitions by William Howells (1831), a young man sees witches sailing across the river Tivy in cockle shells. A cockleshell has associations with the ocean but is also similar to an eggshell. On the other hand, it's also a word for a small, flimsy boat or for unsteadiness in general. In ancient Greece, "putting to sail in a sieve" was an idiom for undertaking an impossibly risky enterprise. In the comedy "Peace," by the Greek playwright Aristophenes (421 BC), it is said that Simonedes has "grown so old and sordid, he'd put to sea upon a sieve for money." The implication is that he has more greed than sense. In England, however, sailing in a sieve had implications of black magic. In "Newes from Scotland: Declaring the damnable Life of Doctor Fian" (1591), two hundred witches plotting to attack and drown the king "went by sea, each one in a riddle or sieve, and went in the same very substantially with flaggons of wine, making merry and drinking by the way." Macbeth also mentions this tradition. So: going to sea in a sieve was a saying for a risky undertaking. A cockleshell was a small, flimsy boat. Altogether, beings who ride in eggshells or sieves might seem tiny, foolish, or laughable. However, some people seem to have actually followed the superstition that witches or fairies setting to sea in eggshells was a genuine danger. But then, as a character remarks in The Round Table Club (1873), "What could witches not make a voyage in?" Witches and fairies (there's that overlap again) were also commonly said to ride on straw, bulrushes, ragwort, thorn, cabbage stalks, fern roots, rushes, and other types of grass. These unusual steeds would carry them through the air at great speeds - a tradition that's survived in modern depictions of witches on flying broomsticks. Ragwort in particular was called the "fairy horse" in Ireland. De Universo, a work by the 13th-century French bishop William of Auvergne, mentions magicians who believed that demons could create magical steeds from reeds or canes. In Discoverie of Witchcraft (again), the fairies "steal hempen stalks from the fields where they grow, to convert them into horses." Isobel Gowdie, on trial for witchcraft in 1662, said that when people saw bits of cornstraw flying above the road "in a whirlwind," it was actually witches traveling. She may have been inspired by the lightness of straw and the way chaff flew in the wind. (Goodare, J. Scottish Witches and Witch-Hunters). Today witches are often depicted riding on broomsticks. The broom was connected to wind, and therefore an appropriate tool for witches who controlled winds and storms. In Germany, people burned an old broom when they wanted wind, and sailors fighting a "contrary wind" would throw an old broom at another ship to make the wind change direction. (Hardwick, Traditions, Superstitions, and Folk-Lore, 1872, p. 117). And here we are back at the idea of sailors and storms at sea! That's the cover of a recent picture book retelling the fairytale with a Halloween theme. However, it reminded me of one of the first known mentions of Tom Thumb.

In Reginald Scot's 1584 work, the Discoverie of Witchcraft, he writes: “...they have so fraied us with bull beggers, spirits, witches . . . the puckle, Tom thombe, hob gobblin, Tom tumbler, boneles . . . and other such bugs, that we are afraid of our owne shadows.” What's Tom Thumb doing in a list of monsters? This baffled me for a long time, but then I looked at the first existing version of the story, "The History of Tom Thumbe," printed in 1621. A childless woman goes to Merlin for help. In this chapbook, Merlin is heavily associated with the occult, and is called (among other things) "a devil or spirit" who "consorts with Elves and Fairies." He tells the woman: Ere thrice the Moone her brightnes change A shapelesse child by wonder strange, Shall come abortive from thy wombe, No bigger then thy Husbands Thumbe: And as desire hath him begot, He shall have life, but substance not; No blood, nor bones in him shall grow, Not seen, but when he pleaseth so: His shapeless shadow shall be such, You'll heare him speak, but not him touch. The metrical version of 1630 is very similar, with some of the same phrasing. These descriptions indicate a Tom Thumb who is not entirely a physical being. Also notice that he doesn't have bones, and there's another demon on Scot's list named the Boneless. There's also a creature called the Tom Tumbler. Is this related to Tom Thumb, or is it just a readalike? On a close reading, the early versions of Tom Thumb contain many references to medieval European superstitions surrounding fairies, witches and demons. In addition to a close relationship with the fairies, Tom shows magical abilities in both of the 1621 and 1630 versions. For instance, he hangs pots and pans “upon a bright sun-beam” as a prank on his classmates. This motif occurs elsewhere in medieval legends. St. Goar of Treves miraculously hung his cape on a sunbeam, and St. Aicadrus did the same with his gloves. Later, Tom boasts that he can "creepe into a keyhole" and "saile in an egge-shel." Travel through keyholes was a common motif for witches, the devil, alps (nightmares), and other fairylike beings. Boating in an eggshell, too, was a popular witch/fairy pastime. Superstitious people would crush leftover eggshells so that these creatures couldn't set to sea in them. That's a post for another time, but eggshell-sailing witches appear even in Discoverie of Witchcraft - the same book that started this blog post. There are many mentions of Tom throughout the late 16th and early 17th centuries. I have a full list on my timeline page. In most of these brief mentions, Tom Thumb is simply a metaphor for something small. However, some give a hint of the story. In the shortened list here, seven works associate him with fairies and/or Robin Goodfellow. Five (possibly six) reference him being trapped in a pudding.

The Thumbling trapped inside food is a common motif which I've discussed before. While his mother is cooking, Tom falls into a pudding and gets boiled inside. In the prose version, the pudding shakes as if "the Devil and old Merlin" are trapped inside, until his mother believes it's bewitched. She hands it off to a passing tinker, who also thinks it must be the devil's work. Tom then breaks out of the pudding and runs home. "Dathera Dad," a Derbyshire tale published in 1895, consists of just this incident. The creature inside the pudding is "a little fairy child." Similarly, the Russian "Devil in the Dough Pan" has an evil spirit who is baked inside bread when a woman forgets to bless the dough. This was a common concept throughout Europe. In Scandinavia, peasant women made crosses on their dough to protect it from trolls (Thorpe 1851, pg. 275). The English did the same in order to "cross out" the witches, to "keep the devil from sitting on it," or to "let the devil out." Thomas Keightley's Fairy Mythology mentions a Somerset woman who would drew crosses on the cakes she baked, in order to stop the tiny, mischievous fairies from leaving footprints on them. The cross was also meant to make the bread rise faster. Perhaps there was a supernatural explanation of warding off evil spirits who might sit or step on the dough. This superstition was known in the 17th century, and perhaps as early as 1252, when King Henry III condemned bakers marking their bread with the sign of the cross. (Roud 2006) This could be connected to superstitions about demonic possession in the Early Middle Ages. Possession was often taken in a very literal, physical-minded way. Demons were depicted entering and leaving the victim's body via the mouth, or sometimes other orifices such as the ear. In his Dialogues, the late-6th-century pope St. Gregory the Great describes this case: "Upon a certain day, one of the Nuns of the same monastery, going into the garden, saw a lettice that liked her, and forgetting to bless it before with the sign of the cross, greedily did she eat it: whereupon she was suddenly possessed with the devil, fell down to the ground, and was pitifully tormented. Word in all haste was carried to [the bishop] Equitius, desiring him quickly to visit the afflicted woman, and to help her with his prayers: who so soon as he came into the garden, the devil that was entered began by her tongue, as it were, to excuse himself, saying: "What have I done? What have I done? I was sitting there upon the lettice, and she came and did eat me." But the man of God in great zeal commanded him to depart." In both the story of the possessed lettuce and the superstitions about crossed bread, the idea is the same. When someone forgot to bless their food - by either praying over it or physically marking it - they became susceptible to any entities which might lurk within. Is this why Tom Thumb appeared in A Discoverie of Witches? Did Scot have demonic food in mind when he included Tom Thumb in the list? Or might he have encountered a version of the story which mentioned sailing in an eggshell? Maybe not. Still, the oldest surviving versions of the story contain allusions not only to magic and fairies, but to demonic activity and witchcraft. Further Reading:

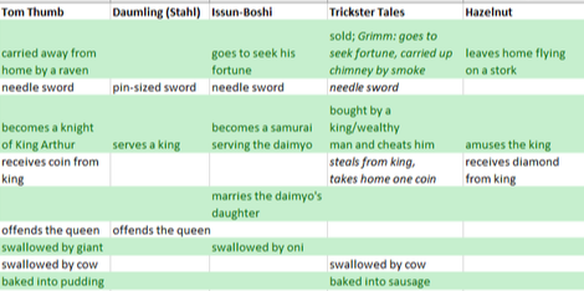

I've been thinking about how in several different tales, a Thumbling figure becomes a favored servant of a king.

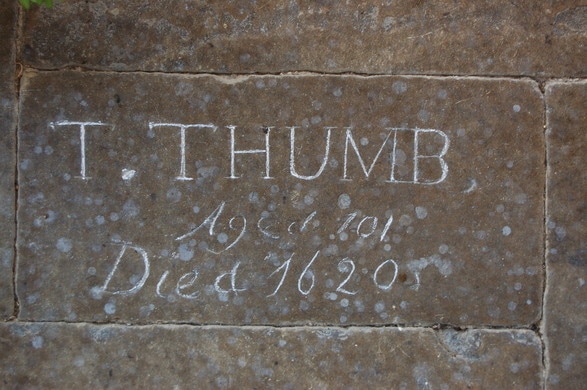

Tom Thumb becomes King Arthur's dwarf and one of his favored knights. (In later versions, he runs afoul of the queen.) Issun-boshi acts as a samurai for a daimyo, or feudal lord. The Hazel-nut Child, in a tale from the Armenian people of Romania, Transylvania and the Ukraine, makes his way to the palace of an African king. Like Tom Thumb carrying home a coin for his parents, the Hazel-nut Child brings home a diamond given to him by the king. Karoline Stahl (the same woman who wrote the first version of Snow White and Rose Red) wrote a story called Däumling. Daumling goes to live in the palace, where he serves the king and several times defends him from assassination attempts. The story was probably inspired by the British Tom Thumb. Both stories have an emphasis on the main character's clothing and needle- or pin-sized sword, as well as an evil queen. Sometimes the thumbling's encounter with the king isn't quite so pleasant. In numerous tales, the thumbling is out in the field with his father, when a rich man, sometimes a noble or king, sees him and asks to buy him. The thumbling sells himself and then runs away, cheating the rich man. In one version, Neghinitsa, the main character does not run away, but ends up working as a king's royal spy until his death. In other stories, like the German "Thumbling as Journeyman," or the Augur folktale "The Ear-like Boy," the Thumbling becomes a robber and a king is one of his victims. In a tale from Nepal (printed in German), the thumbling steals items from the king's palace and eventually wins the hand of one of the princesses. Also in "Thumbling as Journeyman," the little thief takes a single kreuzer, stolen from the king's treasury, to give to his parents back home. Here again is the same motif as Tom Thumb, where the tiny knight asks King Arthur for permission to take one small coin to his parents. In other stories, Thumbling marries the king's daughter - a common ending for fairytales. Issun-boshi marries the daimyo's daughter. In the Philippines, Little Shell and similar characters pursue the daughter of a chief. (See blog post.) In India, Der Angule completes many tasks for a king and finally marries the princess. Some retellings of Tom Thumb, such as Henry Fielding's play, have him woo a princess. I worked a little bit on a chart comparing some of these stories. I included the Grimms' Thumbling among "trickster tales." EDIT: Now with new and improved chart! Most editions of the Tom Thumb fairytale end with the king erecting a monument in memory of the pint-sized hero. Here lies Tom Thumb, King Arthur's knight, Who died by a spider's cruel bite. He was well known in Arthur's court, Where he afforded gallant sport; He rode a tilt and tournament, And on a mouse a-hunting went. Alive he filled the court with mirth; His death to sorrow soon gave birth. Wipe, wipe your eyes, and shake your head And cry,--Alas! Tom Thumb is dead! In fact, there is a real tomb for Tom Thumb. There was once a blue flagstone serving as his tombstone at the Lincoln Cathedral. According to a 1819 edition of the Quarterly review, the tradition was that Tom Thumb died at Lincoln, and "the country folks never failed to marvel at [the blue flagstone] when they came to church on the Assize Sunday; but during some of the modern repairs which have been inflicted on that venerable building, the flag-stone was displaced and lost, to the great discomfiture of the holiday visitants." (The Quarterly Review, 1819, p101). Here is more on the renovations, although it has no mention of the flagstone. What we do still have is a tombstone and a house for Tom Thumb, roughly twenty miles away, in Tattershall, Lincolnshire. "T. Thumb, Aged 101, Died 1620." Is there really someone buried under this marker? Could he be connected to the fairytale? The tombstone is located in the Holy Trinity Collegiate Church and can be found in the floor, near the font. The website of an affiliated church group notes that this Tom Thumb was "47 cm tall" or about 18.5 inches. An Atlas Obscura article cites rumors that he frequently visited London and was a favorite of the King. The date of 1620 is intriguing, because it puts this local legend of Tom Thumb right about the same time we have our first surviving textual mentions of the name - the grave is marked 1620, and the earliest known printing of Tom Thumb was in 1621. (See the Tom Thumb Timeline.) The grave is usually seen decorated with flowers and a poem. Here is an excellent shot from the Atlas Obscura article. Elizabeth Ashworth's blog has another photo, with a closer look at the poem, as well as more history on the church. The poem, by Celia Wilson, doesn't have much information besides this is Tom Thumb's grave, he'd probably have a lot of stories to tell. Then there is Tom Thumb's house, not far away. Most articles on the grave mention it as if it is the actual home of the buried T. Thumb. However, further research shows that it's not a house that anyone ever lived in. It's a decoration. It is located on the ridge of Lodge House, in the Marketplace. The Lodge House is itself a building of historical interest. According to Historic England; "On the roof ridge is a ceramic [14th century] louvre in the form of a gabled house, known as 'Tom Thumb's House'." On medieval buildings, a louvre or louver was a kind of turret or domed structure on the roof, which allowed in air and light but not rain. The Tattershall and Tattershall Thorpe Village Site, available through Wayback, informs us that "The tiny house was thought to keep evil spirits out of the main building. Tom Thumbs house changed from one side of the Market Place when Mr Wright sold his shop." Here's the Lodge House on Google Maps. Can you see Tom Thumb's house? Try looking at this photo from the Village Site. So: two traditions that Tom Thumb died somewhere around Lincoln. And one of them is dated around the same time as the first existing mentions of Tom Thumb.

If any of you readers go to Tattershall any time soon... you know what your homework is. England is swamped in folktales about tiny people – fairies, elves, brownies. However, they only have one thumbling tale that I've found. Most places have multiple variants of the thumbling tale. England is small, but even individual small regions of France and Spain have recorded more than one unique variant. Ireland has quite a few too. I know of two variants from Scotland, Tómas na h òrdaig and Comhaoise Ordaig. But in England, there’s only Tom Thumb. There are a couple of songs that hint at similar stories (see "I Had a Little Husband") but sadly, England's amount of recorded folklore is much lower than that of its neighbors. SurLaLune does list one tale from Derbyshire under Thumbling tales: Dathera Dad. This is a very short tale. A woman is cooking, when the pudding begins to shake and jump around. Frightened, she gives it to a passing tinker to get rid of it. It continues to shake, and finaly breaks apart to reveal a tiny fairy child who runs away crying, "Take me to my dathera dad." This initially seems like just another tale of a tiny fairy, not a type 700 tale. However, the incident is identical to Tom Thumb's adventure in a pudding. The pudding incident was also Tom Thumb's most famous and recognizable feat around the 1600s. He was frequently shown falling into the bowl. In the 1611 Coryat’s Crudities, ten years before the first known printed version of the tale, "Tom Thumbe is dumbe, untill the pudding creepe, in which he was intomb'd, then out doth peepe." In 1625, Ben Jonson’s masque, The Fortunate Isles, mentions "Thomas Thumb in a pudding fat." In 1653, the Lady Margaret Newcastle's "Pastimes of the Fairy Queen" mentioned Tom Thumb "who doth like peice of fat in pudding lye."

"Can I bear to see him from a Pudding mount the throne?" a character asks in the parodic play "Tragedy of Tragedies; Or the Life and Death of Tom Thumb the Great." This is not the same kind of pudding I eat. As an American, the puddings I know would splash rather than break! The original puddings were baked, steamed or boiled and were a primary dish in the everyday diet. They could be made of meat, blood, batter and other ingredients, and formed a solid mass that had to be sliced or broken, as in Dathera Dad. Sidney Oldall Addy theorizes that "dathera" comes from the Icelandic daðra, to wheedle. According to the English Dialect Dictionary, “dather” is to shiver, tremble, or shake with cold or age, and "dathered" can mean bewildered or withered. Dathera Dad is an example of the Runaway Pancake tale, but it's a little different. Most of these versions feature the food actually coming to life and running away; Dathera Dad is a tale of a supernatural being trapped inside the food. The most similar example on that page is a Russian tale called "The Devil in the Dough Pan." Once a woman was kneading bread, but had forgotten to say the blessing. So the demon, Potánka, ran up and sat down in it. Then she recollected she had kneaded the dough without saying the blessing, went up to it and crossed herself; and Potánka wanted to escape, but could not anyhow, because of the blessing. So she put the leavened dough through a strainer and threw it out into the street, with Potánka inside. The pigs turned him over and over, and he could not escape for three whole days. At last he tore his way out through a crack in the dough and scampered off without looking behind him. He ran up to his comrades, who asked him, " Where have you been, Potánka?" "May that woman be accursed!" he said. "Who?" "The one who was kneading her dough and had made it without saying the proper blessing; so I ran up and squatted in it. Then she laid hold of me and crossed herself, and after three livelong days I got out, the pigs poking me about and I unable to escape! Never again will I get into a woman's dough." It's interesting that in these cases the thing inside the food is a fairy or evil spirit. In the Metrical History of Tom Thumb the Little, there's a line regarding this scene: "But so it tumbled up and down, Within the liquor there, As if the devil had been boil'd." In the 1584 Discoverie of Witchcraft, "Tom thombe" is included among a list of monsters and demons. Come to think of it, The Gingerbread Man - probably the most famous version of the Runaway Pancake - has a lot in common with Tom Thumb. He's created after an elderly couple wishes for a child, and his story revolves around being eaten. More on Pudding Tom Thumb and Thumbelina are closely associated in pop culture, for obvious reasons. They've starred together in two direct-to-video movies. They appear as a couple in Shrek 2. I've also found mistaken statements that General Tom Thumb's wife used the stage name Thumbelina.

It's interesting to see how these crossovers treat the characters. The Adventures of Tom Thumb and Thumbelina was basically just a retelling of Thumbelina; despite getting first billing, Tom was barely the deuteragonist and bore no resemblance whatsoever to his original fairytale. Tom Thumb Meets Thumbelina seems like it took inspiration from both fairytales, but otherwise just kind of . . . does its own thing. In a Nutshell, by Susan Price, is a fairly short book published in 1983. It can be a little hard to find in libraries. The main characters, Thumb and Thumbling, are a pair of tiny fairies who anger King Oberon. As punishment, he takes away their powers and gives them to human families. However, the tiny man and woman decide to find each other and get back to Fairyland - which is a tall order for a couple of people only two inches tall. It's one of the most interesting mashup of thumbling tales I've read. Though Thumb is (like Tom Thumb) based in England, and his parents use that name once, his adventures of riding in a horse's ear and being used to fetch stolen goods for robbers are all Thumbling. Thumbling, given to a lonely woman in Denmark, is Thumbelina, and the quest and conclusion are strongly based on The Young Giant. The characters are unlikeable. They're supposed to be unlikeable, as fairies are played up as uncompassionate creatures, but it's still hard to get invested when they act as callous as they do. They only start to come around and grow into better people near the end. One touch I liked was how much we see the danger of their lives; Price does a pretty good job of making it feel like they are constantly threatened. Even their adopted parents could easily harm them, and overpower them by far. I don't think this book is going to be remembered as a classic or anything like that, but it was an interesting read, and I have it on my bookshelf now. Fairytales don't often give side characters names, but Tom's parents have occasionally received monikers. Occasionally.

In R.I.'s 1621 version, Tom's father is Old Thomas of the Mountain, a humble plowman who longs for a son. (His mother seems less involved; she goes along with it, but when she thinks Tom is lost, grieves for about a minute before getting over it.) In Tom Thumb's Folio: Or, a New Penny Play-Thing, for Little Giants (1810), Tom comes of nobler stock. His father is the more genteel-sounding Mr. Theophilus Thumb of Thumb Hall. Thumb is likewise used as a surname in Henry Fielding's parodic play. Here, Tom's father Gaffer Thumb comes back as a ghost. (Gaffer just means old man.) Charlotte Marie Yonge's History of Sir Thomas Thumb names his father Owen, but leaves his mother and crotchety old aunt unnamed. In Louisa Mary Barwell's Novel Adventures of Tom Thumb the Great (1838), Mrs. Thumb is related to the Fingers, a very old and respectable family. In Marianna Mayer's Adventures of Tom Thumb (2001), Tom's parents are Tim and Kate. In 1923, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle and the Detroit Free Magazine both printed a comic titled "Make-Believe," by Jane Corby. Here, Tom has a sister named Dotty. They set out for a picnic lunch in a carriage drawn by a mouse, with spools for wheels, but a cat sets upon them and then everything just gets progressively worse. In the Merrie Melodies short I Was a Teenaged Thumb (1963), the happy parents are "George Ebenezer Thumb and his wife Brunhilda." In the 1941 short Tom Thumb's Brother, his brother is named Peewee. In the 1958 film, Tom's parents are Jonathan and Anna, but this is really an adaptation of the Grimms' Thumbling. So in the majority, only Tom's father is named, and his name is some variation on Thomas, Sr. or Mr. Thumb. His mother has to wait for later adaptations to get a name. Interestingly, Tom's mother, unlike the mothers in other thumbling tales, isn't really as important as his father. In many thumbling tales, it's all about the mother's wish, her desire for companionship. The birth takes place independently of the father's involvement. The child is born in the kitchen, the mother's place of work, while the father is out and about farming; he may not even realize what's happened until his child brings him lunch in the field, and is puzzled to hear a voice calling him "Father." Sometimes, as in Thumbelina, there's no father at all. However, in the original Tom Thumb, the emphasis is on Old Thomas of the Mountain's wish for a son. The cases where they share a name emphasize this; although we see Old Thomas very little after the introduction, and we mainly see Tom interact with his mother when he falls into pudding or is eaten by a cow, he carries on his father's name. That can be Thomas or, more commonly, Thumb. Using Thumb as their real surname is an element of parody, but really does emphasize the theme of sons carrying on the family name and continuing the dynasty. I've noticed a tendency for some thumbling tales to mention the sun - often in roles that overlap. In two stories, the sun is a negative force. Also in two stories, it is somehow the reason why the thumbling is so small, and in a third, it's the reason why mice are so small. On the surface, there's an odd similarity between these tales from North America, Burma, and England, respectively. Upon a closer look, however, these stories all came from very different lines of reasoning. In the Anishinaabe narrative of "Little Brother Snares the Sun," the Sun offends a very small child by shrinking his favorite coat. In retaliation, the boy captures the Sun in a magical net made from his sister's hair. A mouse frees the sun, but in the process shrinks down to its current tiny size. In the Burmese tale "How Master Thumb Defeated the Sun," the Sun curses a pregnant woman so that her child is only the size of a finger. This child later goes to fight the Sun as a result. (Maung Htin Aung, who retold this story in English, theorized that this was a descendant of a solar myth.) So the Sun has the power to shrink things with its heat - something easily observed in the real world, but usually with the excessively high heat of a clothes dryer, not simple sunlight. Typically, the Sun is most familiar as a symbol of warmth and life, which causes plants to grow, but in these stories, it is a negative figure associated with heatstroke and drought. As Maung Htin Aung explains in the notes to Master Thumb,

Here, rain is an ally and the Sun is the enemy. Maung Htin Aung contrasts this with a version from Lower Burma, where Master Thumb is angry at the Sun but his followers are just kind of hanging out. In Lower Burma, the summer heat is not as intense.

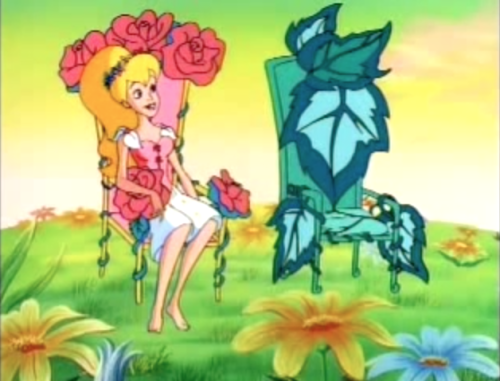

As for Little Brother, Richard L. Dieterle points out that Little Brother's coat is made from a snowbird's skin. The character is thus associated with snow, clouds and winter, the antithesis of the sun and its heat. However, here the Sun is still necessary. It's not as much of a character as the one in Master Thumb's version, just a force of nature. Trapping it leaves the world in darkness, and all will perish without it. Unlike the story of Master Thumb, here the animals (and thus the world itself), instead of helping the sun-catcher, endeavor to save the sun. So those two tales have similarities on the surface, but their internal logic goes a little differently. However, it's interesting that Master Thumb's small size is caused by the Sun. In the English Tom Thumb’s Folio, or, A new penny play-thing for little giants (1791), a solar eclipse "stinted [Tom's] growth." This is stated very casually, as if it's something to be expected from a solar eclipse. Is it because eclipses are times when crazy things happen and nature is turned on its head, or is it that the absence of the sun means that things (from crops to children) cannot grow and develop normally? The sun does actually promote vitamin D, which improves bone growth, so there is a physical, scientific reason. This is also a story written by an English writer. England is not sunny. Here, unlike Upper Burma, the Sun is a more positive figure, and its absence is a bad thing. There are superstitions, particularly in India and Latin America, that an eclipse can be harmful to pregnant mothers, causing children to be born with deformities like cleft lips or birthmarks. In Medieval Europe, the thought was that children conceived during an eclipse would have demons. That's just one retelling of Tom Thumb, but even in other tales, he may, like Little Brother, be a creature averse to the sun. The fairies with whom he was sometimes associated (as in Robin Goodfellow and Nymphidia) were nocturnal beings often depicted living underground. Like quite a few other thumblings, Tom rides a mouse, which also lives underground in the dark. Many thumblings are associated with mice - harnessing them to chariots, being compared to them for a size reference, or actually being mice, like "Hasan the Heroic Mouse-Child." In Norse myth, dwarves are subterranean creatures of shadow, and sunlight will turn them to stone. Dwarves are a step removed from thumblings, but of the same folkloric family. Despite the different lines of logic, the result is still that a few thumbling tales have a similar connection to the sun. Due to the great distance between them and the obviously different origins, it seems to be mere coincidence. Still, the similarities are intriguing. I’ve found quite a few reviews for The Adventures of Tom Thumb and Thumbelina, but none for this little 1997 gem from Golden Films. I finally watched it, and it was surprisingly bearable. It opens with a song, led by Thumbelina flying around on a bird and making the flowers open up in the morning. Accompanied by animals and fairies, as well as a pig playing the piano (???), the song is a stirring piece that really speaks to the beauty of nature and the meaning of life. “Hi dum diddle dee, hi dum dee dum” (repeat 500x). They play the same shot of the animals jumping down a hill at least 3 times. This is not the last time they will reuse animation. That said, I immediately prefer the art style to that used in The Adventures of Tom Thumb and Thumbelina in 2002. Thumbelina is an overworked ruler trying to keep the meadow organized while animals and fairies bicker. It reminds me a little of the Tinker Bell movies. There’s supposed to be a prince, but he was kidnapped when he was a baby (or not, we’ll get to that later). Mainly this just makes me wonder about Thumbelina’s backstory. She’s not a fairy, but they never say what she is. Her duties include dealing with three young delinquents with really annoying voices, and here we have our our kid appeal/comic relief team. Actually, I kind of grinned at some of the interactions here (“What makes you think it was fairies?” Cut to signed graffiti). The work’s getting to her, so she goes to ask advice from an old and inconsistently drawn tree named Oakley. In answer to her plea for advice, he decides to tell her her own backstory. Evidently, the Fairy Queen picked two children from noble families to reign as prince and princess of the meadow. And this just raises more questions. We still don’t know what Thumbelina is. And how did she pick these babies? What were their qualifications? So his advice on government is “wait for your prince to come and then live happily ever after.” I GUESS THAT SOLVES THE PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION. We cut to Tom Thumb, swinging from the curtains. He’s accompanied by a dog that resembles Max from the Little Mermaid, and does not talk. (Even though every single other animal seems to talk in this world, and humans have no trouble communicating with them. Are dogs the exception? Tom then flies around on a tiny motorcycle. I am not making this up. He heads into another room, where an Arthur-esque king and several knights are sitting around a round table. Gee, I wonder if the snobby guy with the nasal voice and the ugly pet bird could be evil. Turns out it’s the king’s son Mordred I mean Medwin, who wants to expand the Castle and open an IHOG (international house of gruel) at the expense of the Great Meadow. The king, however, values nature. Tom tries to give input, but they don’t hear him. He’s eating a snack in the kitchen, when the ugly bird (a raven named Edgar who says “Nevermore” all the time and sounds like a poor man’s Iago), corners a mouse. Tom runs over to defend her with a fork and they have a discussion about how he wants to be an important knight. He feels like he’s meant for more and pulls out a plot-relevant necklace and whoa, that matches Thumbelina’s necklace! What could this mean?!? Then they both get dumped into some batter by a cooking lady with a deep gravelly man’s voice. But it’s all good. Meanwhile, Medwin meets up with some thug and plots to kidnap the king. As usual, I’m baffled by how gleeful they are at the idea of being evil. Like, you can’t have subtlety in a cartoon. And if you were wondering when this film takes place, there’s an odd reference to the War of the Roses (”just like my father to fight over a bunch of flowers”). Thumbelina’s hiding in the bushes when suddenly the King comes riding along with Tom. Tom spots Thumbelina and they talk for a minute, when suddenly the King is kidnapped just offscreen. Tom races back to the castle and is ready to ride out to the rescue, but the knights tell him to stay put. Tom gets suspicious after Medwin and the bird, in public, at the top of their lungs, talk about getting things done their way now and cackle out hysterical evil laughter. Back in the meadow, the animals come running to tell Thumbelina about construction work ruining the meadow. She flies off on her bird to talk to the king. There’s a brief mention of taking away the teen delinquent fairies’ wings if they don’t shape up, which makes me wonder if Thumbelina is a wingless fairy. But she says at some point that Tom is not a fairy, implying that this isn’t the case. More on this later. She meets Medwin, and of course trying to persuade him to save the meadow doesn’t go well. She starts to leave on her bird. Tom’s swinging on curtains again (is this how he always gets around the castle?) and they crash into each other. She assumes Tom’s part of this construction project and gets mad at him. Tom doesn’t know what she’s ranting about, but then he overhears Medwin plotting. My notes at this point read simply, “Oh no,” because, without any preamble, there’s an abrupt cut to Medwin singing and dancing with construction workers and it’s the most bizarre, anachronistic piece of dinner theatre I’ve ever seen. They’re also reusing clips again. There’s also a mention of tearing down the meadow, which is confusing because it’s kind of flat. Tom Thumb arrives with Fiona in the now-fortified meadow. At first Thumbelina and the fairies think he’s a spy, but he explains the truth and lays out a plan to sabotage Medwin’s equipment. Thumbelina and the delinquents volunteer to help, and they all fly off. We cut to a party at night in the meadow. I guess they’ll do the sabotage later? “I think somebody spiked the nectar!” someone says in the background. WHAT? Romance incoming. Tom and Thumbelina start chatting, and mention that The writing is usually okay, aside from the songs, but there are some non sequiturs and oddly emphasized lines. “This might sound kinda weird but I feel kinda like I belong here.” “This may sound even weirder but I sort of feel the same way.” “I have some strange attachment to this meadow.” “Like, you know, like YOU belong here.” A song follows, and they declare their love for one another (that was quick), and … Whaaat’s he doing with his mouth? What follows is the most awkwardly animated kissing scene I’ve ever witnessed. On another note, Thumbelina’s outfit is weird. I thought those things on her shoulders were sleeves. They’re not. They’re just … sitting there, not attached to anything. We cut to Medwin hearing about the sabotage, and this is when I realize that the party was to celebrate the successful mission and we just skipped over the entire thing. Medwin plots to “catch flies with honey;” meanwhile Tom’s preparing to go back and stop Medwin once and for all. Medwin takes a frog hostage and plots to kidnap the fairies when they come to rescue. (I don’t think that’s what catching flies with honey means.) He tosses a turtle away when it tries to stop him, and it lands right in front of Thumbelina’s throne. Hearing the news, she and the delinquents rush off to save the frog. Medwin has completely immobilized the frog by tying his tongue to a piece of grass. (Wow, really?) However, in the process of freeing the trapped animal, Thumbelina and the fairies walk right onto a piece of flypaper. (I still don’t think that’s what catching flies with honey means.) Tom rescues them from Medwin’s birdcage. Medwin was monologuing as usual and mentioned where the king is being kept, so they go to search the dungeons. When they split up, Tom and Thumbelina make up a team and immediately find the king. Medwin has an army of Saxons coming in, so our heroes recruit all the fairies and animals to fight them off. Soldiers are reduced to running and screaming in terror by tiny creatures throwing nuts and water balloons. Oh, and there’s a skunk. And an angry bear. Actually, never mind, this is surprisingly effective, even though the delinquents still aren’t funny. They don’t hit a major roadblock until they realize that they can’t lift the key to the king’s cell. Anyway, it all works out. Tom gets knighted, but now his and Thumbelina’s duties must separate them. So sad. He decides to give her his necklace of plot relevance to remember him by. This summons the Fairy Queen! And it’s revealed that Tom is the long-lost prince of the meadow oh yes of course. Why can’t he remember his childhood? The narrator says he was a baby when he was kidnapped, but he looked like a young child, probably older than five. Anyway, Tom and Thumbelina can now be married and become king and queen (”that is, as long as it’s okay with you both,” the Queen says eloquently). And to reward the delinquents, she gives them new, better wings that look exactly like the old ones. Except all yellow. For his punishment, she shrinks Medwin and Edgar down to a tiny size and puts them in the model of the castle they were planning to build. And everyone lives happily ever after. There’s a weird mention of the two kingdoms becoming one, which doesn’t make much sense, as Thumbelina didn’t exactly make a marriage alliance with the king. So, a few notes. They never say what Tom and Thumbelina are, just that they’re from royal families and they are not fairies. We never see their parents, even in the flashbacks. It’s blurry, but the only people I can identify are a squirrel and a trio who seem to be the teen delinquents, the same age. The Fairy Queen displays the ability to shrink people, and fairies are known in real-world folklore as creatures who steal human babies and replace them with changelings. So my theory is that the Queen kidnapped two children from human royal families and shrunk them. She probably had good intentions, but she’s a fairy. Their morality doesn’t necessarily match up with ours in all the stories. As for animation: there are quite a few errors and reused footage, but what stood out to me was the inconsistencies in the tiny characters’ scale. In the first picture here, Thumbelina is smaller than a man’s eye. In the second, she’s about the size of a man’s foot. Not to mention this flawless bit with Medwin walking. And no, he’s not supposed to be shrinking in this scene. That little blue figure in the background is Tom.

|

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed