|

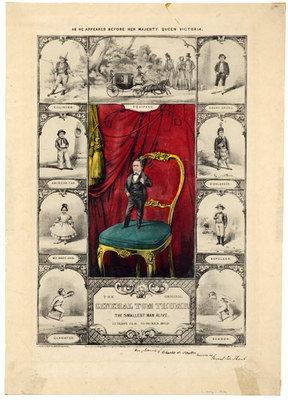

The tompouce (or tompoes) seems to essentially be a sandwich of puff pastry and thick cream, with pink icing glaze on top. The icing is turned orange for King’s Day, and sometimes it is topped with whipped cream. Tompoucen are usually served with coffee or tea or eaten at parties. The brittle puff pastry is notoriously hard to eat. It’s a Dutch and Belgian variant of the mille-feuille, a French dessert dating back to at least the 17th century, with worldwide variants. It’s more commonly called tompoes (or tomcat) in the Netherlands, and tompouce in Belgium. You may also hear of it under the name of custard slice or Napoleon. So why’s it on this website? The story goes that it was created by a baker from Amsterdam, who named it after a stage performer. This performer went by the name Tom Pouce (Tom Thumb). The English Wikipedia says this was Jan Hannema, (1839-1878), a Frisian dwarf who was 28 inches tall. He began performing at fairs when he was only seven and went by the stage name Admiral Tom Pouce. When he was a child, his brothers called him Lyts Tomke, the Frisian name for Thumbling. He also had a cigar named after him. However, other sources, including the Dutch and Polish Wikipedias, say that the performer in question was Charles Stratton, or General Tom Thumb (1838-1883). While performing in Europe, he used the French name General Tom Pouce, which would have then inspired the name of the pastry. Jan Hannema came along using the name after Stratton, and may have taken inspiration from him. Anyway, Tom Thumb or Tom Pouce had become a generic term for a little man or for anything miniature. The name was given to little carriages, a geranium, an American steam locomotive, and a type of women’s parasol in France. I think the parasol was named with Charles Stratton in mind, though.

I’m not sure whether size had anything to do with the tompouce’s name. It seems to be smaller than a mille-feuille—at least, it has only one layer as opposed to a mille-feuille’s two. As mentiond earlier, the pastry’s also known as a Napoleon in some places, when made with almond-flavored paste. It does seem significant that Napoleon is famous for being short, and Charles Stratton even played him a few times. However, the name may actually stem from napolitain, as in “from Naples.” The dessert definitely predates General Napoleon and there’s no obvious connection between the two. The Russian Napoleon is triangular in shape, with slightly more layers. This variant apparently does have connections to celebrating Napoleon’s defeat in 1812. Perhaps this was part of the corruption of “napolitain” to “Napoleon.” I'd need much more information to find out if any of these connections are real, and how the pastry was actually created. That information may be lost to time. However, this makes for another interesting bit of trivia on how the fairy tale leaves impressions on modern culture. And it puts the swallow cycle in a whole new light.

1 Comment

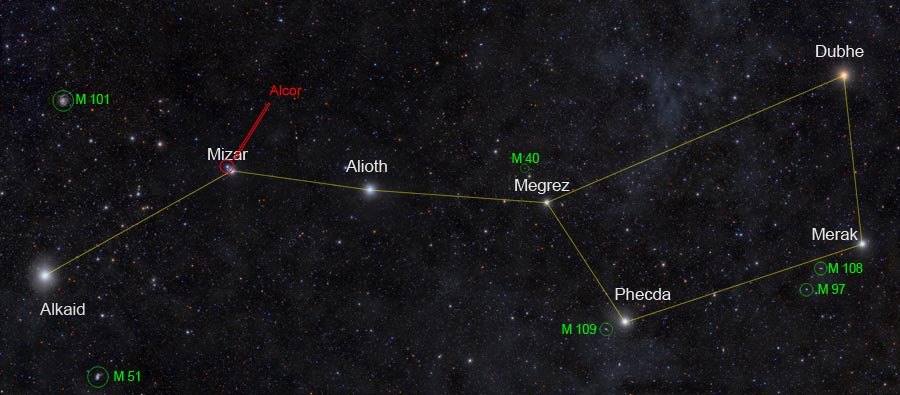

Tom Thumb is a star in the constellation of the Big Dipper. Specifically, Alcor, a barely-visible star right in the middle of the dipper’s handle, piggybacking on a star called Mizar. According to Le Petit Poucet et la Grande Ourse, or “Tom Thumb and the Great Bear,” by Gaston Paris, there's a little-heard-of tradition in Wallonia regarding this constellation. Here, its name is “Chaûr-Pôcè."

The idea is that the four stars on the right are the wheels of a cart, and the three in line on the left are horses. Sitting on the horse in the middle is tiny Alcor. This is the driver, Pôcè – or Poucet, i.e. Tom Thumb. (This is sourced from Grandgagnage’s etymological dictionary.) Apparently the tradition is that Poucet is hanging beneath the belly of the second horse, trying to reattach the harness. I’ve seen other sources refer to this constellation as a wain or wagon, and there was an Arabic tradition of calling Alcor and neighboring star Mizar the horse and rider, but this is the only time I’ve heard Tom Thumb in astronomy. Paris is basing all this in theories that all myths are connected and furthermore they all have astronomical ties. He links it further, by a few leaps, to the myth of baby Hermes stealing the oxen. This seems a bit much. (Like Tom Thumb being Tam Lin.) However, many variants of the Thumbling folktale do include him riding horses and donkeys (usually perched in an ear) or driving a plow pulled by horses or oxen. This, coupled with how hard it is to see Alcor, makes the name seem quite appropriate. We open on a man named Jonathan chopping wood. A voice from midair calls him, and turns out to belong to the Queen of the Forest, who asks Jonathan not to cut down the tree. He doesn’t believe her, but she talks him into agreeing, and says she’ll grant him three wishes. Then she vanishes, proving that she’s magical. He goes home for dinner and says grace before he eats. This is such a fifties movie. He keeps trying to tell his wife about the Queen of the Forest, but stops, complains about having cabbage for dinner, and wishes for sausage. Bing, there’s a sausage. He starts talking about how beautiful the Queen was; his annoyed wife wishes sausage was on his nose. Blah blah blah. This isn’t even Tale Type 700! Finally this blows over and they make up, and the wife gives us The Line: “Even if he were no bigger than my thumb.” Cut to outside. It’s dark. Owls watch as something rustles in the grass, heading slowly towards the tiny house. In the silence, someone’s whistling but we can’t see who. This is shot like a horror movie. Jonathan and Anna are asleep (in different beds. Such a fifties movie). 13 minutes in, we finally see Tom Thumb, dressed in a (normal-sized) fig leaf. I first saw this dubbed in Spanish, and with the low-quality video and annoying high-pitched voice, I thought he was a woman. It didn’t help that the leaf looks like a dress. Anyway, as Tom warms himself by a candle, he announces that he’s their son. He’s actually five and a half inches tall, so quite a bit bigger than a thumb. The overjoyed couple place the tiny adult man in a baby’s cradle and bid him goodnight. This was one thing that felt weird about the movie – Tom is a child, really, and everyone treats him as such, but he’s played by a grown man. Not that Russ Tamblyn was bad in the role. He has a very playful Peter Pan-like air, and he does some great acrobatics, but I still feel like having a child in the role might have been better for effect. Tom varies between being an obvious cutout and a doll. I should mention that this film won an Oscar for special effects. For its time, this was pretty good. Anyway, Tom is woken by his toys, who want to sing and dance for him. There’s a stereotypical Chinese doll named Con-Fu-Shon. I think there’s also a golliwog running around in the room, just so twenty-first-century viewers can feel sufficiently cringy. Also among Tom’s toys is an angry-looking bride doll (clearly a woman trying with her all not to blink), who’s the only one who doesn’t come alive. Then we get to the LONGEST DANCE SEQUENCE EVER. After five hours straight of Tom’s whimsical insanity, it’s morning. Tom and his father go out to the fields to work, and are spotted by two crooks who want to use Tom in their heist. Tom is naïve and trusting, but his father knows better and sends them on their way. On the way back, we encounter Woody, some random guy who’s in love with the Queen of the Forest. They can only be together if he kisses her and she becomes mortal, but they keep dancing around the subject and this is our excuse for a plot, people. Woody heads off and encounters Jonathan and Tom. He offers to take Tom to the upcoming local fair, and Jonathan agrees. WHY am I watching a random guy singing about STOP-MOTION-ANIMATED SHOES? I DON’T KNOW! Anyway, Woody and Tom run off to buy some shoes. The shoemaker gives Tom some miniature shoes off a keychain. However, in the midst of the dancing people, Tom nearly gets trampled, and grabs onto a balloon’s string and floats away. He floats right over the castle that the two crooks are trying to break into. (I call no way.) They shoot down his balloon with a slingshot and catch him. He thanks them for saving him, and they con him into helping them steal a bag of gold. They claim it’s for orphans. Then they send him off through the dark, scary swamp, with a single gold coin for his troubles. Fortunately, he’s rescued by the Queen of the Forest, who then has a argues with Woody. Finally Tom sneaks home, afraid of getting in trouble with his father. (Both of these scenes have the man yelling at Tom and the woman saying “Don’t yell at him.”) Along the way, Tom accidentally drops his coin into a batch of bread that his mother’s cooking up. Tom is sent off to bed, and the toys decide to bring out a doll called “The Yawning Man” to help him fall asleep. This, of course, involves singing. NOOOO Okay, okay. The soldiers are looking for whoever robbed the treasury, and stop by Jonathan and Anna’s house. Anna offers them some breakfast, but wouldn’t you know it, she gives them the bread containing the coin. The soldiers decide to arrest the couple. Tom and his toys hear the commotion and try to get out, but Tom can’t open the door. This was actually a pretty sad scene. Finally Tom gets out and finds Woody. Fortunately, Woody somehow knows where to find the thieves. They track them down to an abandoned castle, where we find the thieves counting “Two for you and two for me, three for you and three for me…” in a scene straight out of Maria como un Ajo. Meanwhile we’re continually cutting back to Jonathan and Anna, who are about to be sentenced. Their punishment is 24 lashes. And I guess that’s it. This seems a bit underwhelming to me, especially since they’re still playing the town lasher as a clumsy, goofy person who gets tangled in his own whip. He seems to have his hood on wrong. Tom plays tricks on the robbers for a few very long and repetitive minutes, and then Woody starts throwing punches and the fight commences. After that fight scene, presumably all of the participants have brain damage. So many head blows. I think everyone spent at least a few minutes unconscious except for Tom. The thieves finally figure out what’s going on and decide to escape on their horse, but Tom is hiding in its ear and directing it towards town. This looks way more uncomfortable for the horse than I’d envisioned it. Jonathan gets his shirt torn off so that he can be lashed, and he turns out to be pretty toned, at least in the back region. But just before they can whip him, the thieves come flying in on their horse and fall off, sending gold flying everywhere, and Tom shouts that they’re the culprits. They’re about to escape, but Woody catches up with them and punches them out. Hurray! The Queen of the Forest pops in, and Woody kisses her. They both vanish momentarily, and her gown and diamond crown transform to a peasant dress and flower wreath, which . . . I guess . . . means she’s mortal now . . . ? Anyway, they get married and everyone is standing around celebrating. Tom is the groom figurine on the cake, standing next to that bride doll from earlier. He kisses her on the cheek and she comes to life (or perhaps simply gives in to the crippling urge to blink). They dance around the cake and everyone sings. So . . . are kisses in this universe magical?

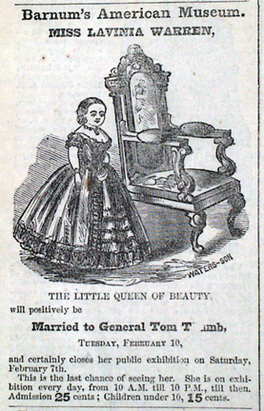

This movie left a lot unexplained, like how Tom actually came into being. It’s harmless, but doesn’t have much substance, and some of the elements (such as Con-Fu-Shon) haven’t aged well. Although Tamblyn’s acrobatics are excellent and the stop-motion effects are nice, it suffers from long musical sequences which completely halt the narrative for minutes on end. Storywise, it’s a fairly straightforward Thumbling retelling, but with far too much padding. The Woody/Forest Queen romance was unnecessary. Overall, it was an interesting watch - not great, but okay.  The extravagant wedding of Charles Stratton – known by the stage name General Tom Thumb – and Lavinia Warren was a diversion in the midst of the Civil War. The cause of their short stature is unknown, although they probably had a form of growth hormone deficiency. Both were recruited as performers by P. T. Barnum. The wedding made headlines all over the country. Newspapers reported vast crowds attending the miniature wedding and following the newlyweds’ carriage. Wedding photos and thousands of reception tickets were sold. On their honeymoon, they visited President Lincoln and had a reception at the White House. This was in 1863. In following years, Tom Thumb Weddings or miniature weddings became a popular activity. These pageants were clearly inspired by the Strattons’ wedding, and mimicked the spectacle of the perfect miniature wedding. The actors, children dressed up in adult wedding gear, were typically ten and under and sometimes as young as two. In some places, performances included more than 100 children playing the wedding party and guests. The vows were usually written comically. These plays served as fundraisers, entertainment, and/or a way to teach young children about etiquette. Old articles, as well as a script published by Baker's Plays in 1898, refer to Tom Thumb’s bride by the name Jennie June. The cause for using this name is unclear, but it shows up in quite a few other places. A song called “Little Jennie June” was printed in Album Melodies by Richard Ferber in 1892, and a character Jenny June appeared in a set of paper doll advertisements in 1876. In the 50's, one could buy a Jennie June china doll kit. In the case of the Tom Thumb Wedding skit, it’s possible that June is a reference to the tradition of June weddings. A couple of blushing brides were known as “Lillian Putian,” daughter of “Mr. and Mrs. Midget.” Other accounts described a double wedding with Fred Finger and Nellie or Milly May. However, it seemed more common, especially in later years, to use the performers’ real names. The practice seems to have peaked in the first half of the 20th century and fallen off in the 70’s and 80’s, but Tom Thumb Weddings still pop up now and then. At least one was performed in 2008. The name is the only thing connecting this practice to its origins in English folklore, but it makes for an interesting side to the study of the folktale type. Sources and pictures A news article on the phenomenon: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/melanie-benjamin/royal-wedding_b_850540.html

Images of General Tom Thumb and Lavinia Warren: http://www.brightbytes.com/collection/tomthumb.html An article on the Stratton wedding in 1863: http://www.nytimes.com/1863/02/11/news/loving-lilliputians-warren-thumbiana-marriage-general-tom-thumb-queen-beauty-who.html?pagewanted=all An invitation to a Tom Thumb wedding performance: http://www.aweddingtradition.com/tom_thumb_invitation.htm A brochure for the Tom Thumb Wedding play: http://digital.lib.uiowa.edu/cdm/ref/collection/tc/id/20862 Some pictures: http://search.tacomapubliclibrary.org/images/dt6n.asp?krequest=series+contains+A6009 A performance in 1991: http://www.nytimes.com/1991/06/16/news/tom-thumb-weddings-only-for-the-very-young.html Some more pictures: http://blog.kittanningonline.com/2011/05/tom-thumbs-wedding/ This picture is from Tattershall in Lincolnshire, England, where they boast of having Tom Thumb's house and grave. The famous T. Thumb here was about 18 inches tall. I wonder what the story was behind this.

There’s another story that he died at Lincoln and there was a blue flagstone (now lost) marking his grave in the Cathedral there. That's not too far away. As far as the folktale itself goes: the earliest mention I could find of Tom Thumb is in 1579. The earliest print version (1621) claims that “little Tom of Wales, as big as a miller’s thumb” is a very old tale, older than Tam Lin (which dates at least to 1549). Just for reference, Tattershall’s eighteen-inch-tall T. Thumb would have been born in 1519. Within the ballad, the most popular version of the tale - where Tom is a knight of King Arthur - there are no solid dates. Tom Thumb and Jack the Giant Slayer are both examples of later fairytales using the Arthurian mythos as a backdrop. The first existing mention of King Arthur dates to the year 830 and there are several theories as to who the character might have been originally based on. Henry Altemus' edition of "The History of Tom Thumb," puts Tom's year of birth in 516. The version that adds two chapters, when Tom Thumb stays in Fairyland for two hundred years before returning to serve King Edgar (the Peaceful, I think - King from 959 to 975), placing his year of birth and the reign of King Arthur somewhere in the 700's. There is one very different version, Tom Thumb’s Folio, or, A new penny play-thing for little giants, published in 1791. This one dates Tom’s birth to 1618, the year Sir Walter Raleigh died. It even gives us Tom’s birthday. In this version, a solar eclipse caused his small size, and there was a total eclipse on June 21. And he’s from Northumberland. (Ha ha ha.) There are warnings that a fairy knight named Tam Lin haunts a local forest. Ignoring these rumors, a daring young woman sets out to pick flowers there, only to come face-to-face with the knight himself. One thing leads to another, and when she becomes pregnant, Tam Lin explains that he is a prisoner of the fairies and only she can rescue him. As he changes through various monstrous forms, she must hold him tightly and never let go until he becomes himself again. So goes the Scottish ballad.

As I researched Tom Thumb, I happened across the theory that Tam Lin – a.k.a. Tamlane, Tomalin, etc. – is related to Tom Thumb, or even that he is Tom Thumb. This theory hinges on both being descended from an older Scandinavian character named Thumbling or Thaumlin. William Adolphus Wheeler promotes this theory in his 1866 work A Dictionary of the Noted Names of Fiction. It also pops up in Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable (1898), Palmer’s Folk-etymology (1882) and David Fitzgerald’s “Robin Goodfellow and Tom Thumb” (1885). Unfortunately, these authors seem to be reaching, and none of them ever seem to say where they got this idea. Reading Fitzgerald, one might think that you could definitively connect any folktale from any culture, as long it’s connected in some way to thumbs, fingers, hands, feet, short stature, short measure of time, the number five, the number seven, the name Thomas, the syllables Thumb, Tom, or Tam, or the letter T. If you define the giant Finn MacCool as a thumbling, I think we might be talking at cross purposes. The names may be similar, but that's because Tam, Tom and Thomas are everyman names (like Hans or Jack), nothints at a vast shared history. Characters from all sorts of wildly different stories share these names because they are generic. Furthermore, Thumbling and Tam Lin are not etymologically related at all. (Thumbling is Little Thumb, and Tam Lin is Thomas of the Waters.) So are there any sources that actually discuss Tam Lin’s size? Has some old reference to Tam Lin’s diminutive stature been lost, as the previously mentioned authors suggest? As described in nearly all versions of the ballad, he seems to be of normal stature. I found a couple of sources that, discussing the ballad, described him specifically as a dwarf. And there are a couple of versions that have him as a “wee, wee man.” One of these segues into the first verse of another ballad, appropriately titled “The Wee, Wee Man” (“the least that eer I saw”). This is presumably just because the two ballads got muddled up - in reality, this is common, unlike the nice, neat folktale family tree theory. In Nymphidia (1627), Michael Drayton uses Tomalin and Tom Thumb as a miniature fairy knight and page, respectively. This is more likely to be an example of someone using random stock fairy names than a hint at a lost tradition. He also mixes in Shakespeare’s Oberon and Titania, and Roman mythology’s Proserpine and Pluto. In the end, the stories of Tam Lin and Tom Thumb have no shared elements whatsoever. That is much more important than the similarity of the names. The earliest surviving print version of Tom Thumb was produced in 1621. In the foreword, the author specifically mentions a “Tom a Lin, the Devil’s supposed bastard” alongside other Toms – notably, all of normal size – before reasserting that he is writing about Tom Thumb (or “Little Tom of Wales”), supposedly the oldest of all. That doesn’t mean there isn’t an older oral tradition we can only guess at, where Tom and Tam have some long-forgotten connection. But often, the theory of the Great Grandpa of All Other Folktales Ever simply gets silly. In Murray’s Ballads and Songs of Scotland (1874), a connection is drawn between Tom Thumb, Tam Lin, and the Norse god Thor. I still don’t understand what on earth Thor has to do with Tam Lin, but the author does make a point that Thor plays a Thumbling-esque part in his encounters with giants – hiding in the finger of a glove, or running to escape a giant’s foot. I find that fascinating. (tam-nonlinear.tumblr.com/ and tam-lin.org/ were very helpful in researching this post.) A fair amount of thumbling tales mention marriage. However, I had thought that Tom Thumb was doomed to die young and childless. Most renditions of his story end this way, which is honestly a bit of a downer. However, it turns out a few authors have seen fit to set Tom up with a lady friend.

Princess Huncamunca in the play Tom Thumb by Henry Fielding (1730). The play would later be edited and expanded as The Tragedy of Tragedies, but the central idea was the satire and a huge, tangled love dodecahedron. Like most of the cast, Tom has multiple love interests; in his case, these are King Arthur’s wife Dollalolla, Arthur’s daughter Huncamunca, and the giantess queen Glumdalca. In 1733, it was re-adapted as The Opera of Operas; or Tom Thumb the Great, by Eliza Haywood and William Hatchett. This focused more on parodying opera tropes, so the the ridiculously tragic deaths are reversed and Tom marries Huncamunca. Tom Thumb and Hunca Munca were the names of Beatrix Potter’s pet mice and the stars of The Tale of Two Bad Mice. Grumbo’s daughter, in “Tom Thumb's folio, or, A new penny play-thing for little giants,” printed in 1791. This version dispensed plenty of details. Tom’s father was Theophilus Thumb and the family was from Northumberland (ha.ha.ha.). Tom was born in 1618 on the day of a solar eclipse (July 21?). In this story Tom defeats Grumbo, king of the giants, and becomes a major political force in the kingdom. (This is very different from the typical story where he functions solely as a knight and a sort of clown whose duties seem to boil down to performing for the king - he doesn't actually do much other than make a good appearance.) He marries Grumbo’s daughter, an unnamed giantess. They have twin boys named Gog and Magog, “nine hundred times” as big as Tom. Princess Poppet in “Harlequin and Tom Thumb, or Gog and Magog and Mother Goose’s Golden Goslings,” a pantomime performed in 1853. Here, Tom rescues King Arthur’s daughter Princess Poppet from the giant Grumbo. Arthur is reluctant to bless the marriage, but Mother Goose shows up and there’s a harlequinade and Tom and Poppet get married. Apparently the pantomime was fun, if somewhat incomprehensible to some critics. An unnamed bride in Extraordinary Nursery Rhymes and Tales: New Yet Old (1876) features retellings of fairy tales and nursery rhymes in verse. Here, with help from King Arthur and the fairies, Tom Thumb begins looking for a proper wife. At first he can’t find a girl of proper size, and then he meets twenty little fairylike beauties and can’t choose between them. However, he eventually ends up with one and is perfectly happy (the other girls serve as bridesmaids). His new wife has six babies per year, alternating between daughters and sons, and they need help from Arthur and Guinevere to feed them all. Queen Smilinda in The Lilliputian Magazine; or, Children's Repository (1770s) contains a story called "The Lilliputian History," detailing the life of a King Tom Thumb of Lilliputia. The story is original, but begins with King Thumb visiting the court of King Arthur in a clear nod to the British tale. Smilinda is the princess of a country called Yarthonia. They have a son, born in 1514, whose name is not given. The most common names in Tom Thumb weddings were Lillie Putian (with many variations) and Jennie June. |

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed