|

A few months ago I reviewed The Story of the Little Merman, a gender-swapped retelling of The Little Mermaid from 1909. I've come across a few modern parallels, but by far the best recent example is one from 2023: The Silent Prince, by C. J. Brightley. The delightfully cocky mer prince Kaerius falls for a human princess named Marin whom he saved from drowning, and seeks to become human so that he can officially meet and woo her. He quickly finds himself in the middle of a complicated political situation, all while learning to be a humbler person.

This is part of the Once Upon a Prince series, released by the indie publisher Spring Song Press, which is also run by Brightley. It includes twelve books, each by a different author, which retell popular fairy tales with a focus on the male leads and often a twist to the plot. The Silent Prince owes a fair amount to Disney. The "sea witch" role is filled by a giant kraken (although not as malevolent as Ursula) and Kaerius gives up his voice, not his tongue. However, there are also some elements from Andersen; Kaerius experiences pain from dancing in tight boots that he's not used to, and the story nods to the original story's themes of self-sacrifice. I've been on a kick of reading mermaid novels for quite a while now, and found true underwater settings fairly rare, probably because they're difficult to write well. It really requires a different mindset. It's easy for underwater worldbuilding to get cheesy with ocean puns, talking fish friends, and so on. But although the novel takes place 95% on land, Brightley's merfolk feel wild and alien in a way that I've rarely seen. This novel is at its best in the worldbuilding and the scenario of a merman adjusting to land. Plenty of mermaid stories feature the mermaid character being a fish out of water, but Brightley really sinks her teeth into it - for instance, we learn that licking someone's hand is a polite greeting among merfolk, while hugging is considered a show of great vulnerability because it exposes your throat. There's an element of realism in play, as seen by Kaerius experiencing numerous health concerns when he comes ashore after inhaling water. The way that Kaerius communicates is also refreshing. In a lot of retellings, the mermaid can't communicate with the prince at all. But Kaerius is used to sign language as part of normal merfolk life, so he just naturally signs to the humans he meets, and the princess and her guards gradually start to learn enough to understand him. There are a couple of letdowns. The ending felt rushed; after such an in-depth and colorful story, this was particularly disappointing. And although we spend a lot of time with Kaerius and his character development, we never really gain a deeper understanding of Princess Marin. Kaerius does realize that his initial impression of Marin was mere infatuation, and that he needs to actually get to know her as a person. This should be a good start! But then he gets to know her fairly easily, she turns out to be a kind and noble person, and... that's it. They have a sweet and straightforward romance. She's surprisingly chill about his strange habits and some reveals that should have been shocking; it feels like we never really get to see beyond the surface with her. We honestly get to see more of Kaerius's relationship with the human guard who hosts him. Overall, I'd class this as a solid retelling, fun and with a clean romance. It jumped right to the top of my list of favorites, and I'd suggest it to anyone who enjoys retellings and developed worldbuilding.

0 Comments

I'm excited to say that Writing in Margins made it onto Feedspot's Top 45 Fairy Tale Blogs!

A while back, I discovered that an author named Ethel Reader had written a gender-swapped retelling of "The Little Mermaid" all the way back in 1909. Well, actually there are a lot of other elements mixed in. The story The novella begins by introducing the undersea kingdom of the Mer-People. In the kingdom is the Garden of the Red Flowers; a flower blooms and an ethereal, triumphant music plays whenever a Mer-Person gains a soul. The Little Merman, the main character, is drawn to the land from a young age. One day he meets a human Princess on the beach, and they quickly become friends. The Princess eventually explains that her kingdom is plagued by two dragons. She is an orphan, and the kingdom is ruled by her uncle, the Regent, until the day when a Prince will come to slay the dragons and marry her. The Little Merman wants increasingly to have legs and a soul like a human; there’s a sequence where he goes into town on crutches and ends up buying some soles (the shoe version). However, after some years, the Princess tries to take action about the dragons and protect her people. The Regent, who is actually a wicked and power-hungry magician, sends her away to school. The Little Merman asks her to marry him, but she explains that "I can't marry you without a soul, because I might lose mine" (p. 52). The Little Merman plays her a farewell song on the harp. The Little Merman talks to the Mer-Father, an old merman who explains that he once gained legs and went on land to marry a shepherdess whom he loved. However, when he made the mistake of revealing who he really was, the humans were terrified and drove him out. Unable to find a soul, he returned to the sea. The Mer-Father tells the Little Merman how to get to an underground cave, where he will meet a blacksmith who can give him legs. He gives him a coral token; as long as he keeps it with him, he can return to the sea and become a merman again. The Little Merman goes to the blacksmith, who happens to be a dwarf living under a mountain. He pays with gems from under the sea, and the blacksmith cuts off the Merman’s tail to replace it with human legs. The Little Merman wakes up on the beach, human and equipped with armor and weapons. The Mer-Father has also sent him a magical horse from the sea. He proceeds to the castle, where people assume he is one of the princes there to fight the dragon and compete for the Princess’s hand. The Princess, now eighteen years old, has just returned from college. The Princess doesn’t acknowledge the Little Merman—who is going by the name “the Sea-Prince”—and he’s afraid to identify himself after the Mer-Father’s story of being cast out. Every June 21st the Dragon of the Rocks appears and people try to appease it with offerings of treasure; every December 21st the same thing happens with the Dragon of the Lake. The princes go out to fight the Dragon of the Rocks, but it vanishes through a solid wall of the mountain; they all give up in disgust except for the Little Merman, who has been spending time with the Princess and now shares her righteous fury on her people’s behalf. With help from the dwarf blacksmith, he finds a way into the dragon's lair and slays it. The people adore him, while the resentful Regent spreads rumors against him, and the Little Merman is secretly disappointed that he hasn’t earned a soul. In December, the Little Merman goes out to fight the Dragon of the Lake. It drags him underwater, but he can still breathe underwater, and slays it too. The wedding is announced, but the Little Merman is conflicted; he still doesn’t have a soul, and if the Princess marries him, she will lose hers. He also fends off an assassination attempt from the Regent, but saves the Regent's life. The next morning, the Little Merman announces to the people that he is from the sea and has no soul. The Princess always knew it was him and loves him anyway, but everyone else rejects him and the Regent orders him thrown in prison. After a trial, he will be burned to death. The Princess gets the trial delayed and begins studying the royal library's law books. The Merman waits in jail, only to hear the Mer-People calling to him. They offer to break him out of jail with a tidal wave, but he refuses, worried about the humans. The Dwarf Blacksmith also offers him an escape, reminding him that he won’t get a soul either way; the Merman refuses again. Then the Little Merman's loyal human Squire visits. He has raised an army from the countryfolk, with the Sea-People and the Dwarfs also offering to fight. It may be bloody, but if they win, the Little Merman will have a chance to earn a soul. The Little Merman vehemently refuses; he will not kill his enemy, and he knows the kind of collateral damage that the Sea-People and the Dwarfs will bring to the kingdom. He gives the Squire his coral token, telling him to take it back to the Mer-Father; he is not returning to the sea. Alone in his cell, waiting for death, he hears the music that means a merperson has won a soul. The next day is the trial, where the Regent accuses the Little Merman of deception and treason. The Princess speaks up in his defense. The only issue is that the Little Merman doesn’t have a soul, so she reveals that she has found a record of a man from the Sea-People who came on land, was similarly accused of having no soul, and asked how he could get one. A local Wise Man told him that he would only win a soul when the Wise Man’s dry staff blossomed; at that moment, the staff put out flowers. The judge and lawyers decide to try this out, the Regent gleefully offers his staff, and the staff blossoms. The shocked Regent confesses all his crimes, including that he was the one who brought the dragons. The Little Merman intervenes to spare him from execution. The Little Merman and the Princess get married and rule the kingdom well, and there is a new red flower in the underwater garden. Background and Inspiration The Story of the Little Merman was initially released in 1907; it was a novella, with the same volume including an additional novella, The Story of the Queen of the Gnomes and the True Prince. Both were illustrated by Frank Cheyne Papé. The Story of the Little Merman was reprinted on its own in 1979. I have been unable to find much information about Ethel Reader, or any books by her other than this. In the dedication, she describes herself as the maiden aunt to a girl named Frances. The story itself has many literary allusions. It’s maybe twee at times but also had a lot of really funny lines. The overall mood made me think of George MacDonald’s writing. Some quotes that stuck with me:

First and most prominently, “The Story of the Little Merman” is an allusion to “The Little Mermaid.” Not only is the title similar, there is the description of the Garden of the Red Flowers, paralleling the Little Mermaid’s garden. There is also the overall plotline of the merman longing for both his human love and an immortal soul, going through a painful ordeal to become human, and winning a soul through self-sacrifice - with a final moral test where his loved ones beg him to save himself by sacrificing everything he's been fighting for. (One distinction: The Little Mermaid just gets the chance at an immortal soul, while the Little Merman actually gets his soul, along with a happily-ever-after with the Princess.) That's about where the similarities end. Reader’s book adds elements of dragon-slayer stories, and - most prominently - it plays on Matthew Arnold’s merman poems. “The Forsaken Merman” (1849) is one I recognized. Related to the Danish ballad of Agnete and the Merman, it tells of a merman who has taken a human wife and has children with her. The human woman hears the church bells and wishes to go back to land for Easter Mass: “I lose my poor soul, Merman! here with thee.” Once there, she never returns, leaving her husband and children forlorn. “The Neckan” (1853/1869) was new to me. This poem also deals with a human/sea-creature romance and the question of souls and religion. The Neckan takes a human wife, but she weeps that she does not have a Christian husband. So he goes on land, but when he introduces himself, humans fear and revile him. This is directly based on a Danish folktale, collected in Benjamin Thorpe's Northern Mythology: A priest riding one evening over a bridge, heard the most delightful tones of a stringed instrument, and, on looking round, saw a young man, naked to the waist, sitting on the surface of the water, with a red cap and yellow locks… He saw that it was the Neck, and in his zeal addressed him thus : “Why dost thou so joyously strike thy harp ? Sooner shall this dried cane that I hold in my hand grow green and flower, than thou shalt obtain salvation.” Thereupon the unhappy musician cast down his harp, and sat bitterly weeping on the water. The priest then turned his horse, and con tinued his course. But lo ! before he had ridden far, he observed that green shoots and leaves, mingled with most beautiful flowers, had sprung from his old staff. This seemed to him a sign from heaven… He therefore hastened back to the mournful Neck, showed him the green, flowery staff, and said : " Behold ! now my old staff is grown green and flowery like a young branch in a rose garden ; so likewise may hope bloom in the hearts of all created beings ; for their Redeemer liveth ! " Comforted by these words, the Neck again took his harp, the joyous tones of which resounded along the shore the whole livelong night (1851, p. 80) Arnold edited his poem after its first publication. In his first version, the priest rejects the Neckan and that’s it. In his second version, Arnold reintroduces the theme of the miraculous flowering staff. However, instead of being overjoyed like the Neck in the folktale, Arnold's Neckan continues to weep at the cruelty of human souls. The flowering staff is an old and widespread trope; it appears in the biblical story of Aaron, in a legend about St. Joseph, and most similarly in the medieval legend of Tannhauser, where a knight asks a priest if his soul can still be saved after he dallied in an underground fairy realm. While The Story of the Little Merman is clearly influenced by Andersen’s “The Little Mermaid,” it is equally or more inspired by “The Neckan,” even directly quoting it in one scene. I have never been a fan of the motif that merfolk don’t have souls, but it was an accepted idea in medieval legend. I recently read Poul Anderson’s The Merman’s Children, inspired by the story of Agnete and the Merman and thus distantly related to The Story of the Little Merman. In Anderson’s book, receiving souls is a Borg-like assimilation that costs the merfolk their old identities and memories. It’s a bitter take on the conflict between Christianity and paganism. Reader has a much more positive view on merfolk gaining souls. The merfolk are beautiful, but they just kind of exist, doing no harm and no good. They and other supernatural beings are part of nature. The Little Merman comes truly alive through his time on land, learning passion and emotions, and how to care about people other than himself. He learns how to feel anger and hatred, but these can be positive, the story explains—anger on behalf of vulnerable people, hatred of evil and greed. I like how the story raises the question of how the Merman actually acquired his soul. Did he earn a soul in the moment that he selflessly faced death and sent away his last chance of escape, or was his soul developing all along from the moment when he first saw land? The story hints pretty strongly that it’s the second one. I also really like the play on the Little Mermaid's final choice in Andersen's original. Here, this scene is greatly extended and really delves into the alternatives, raising different possibilities - might the Little Merman return to his old existence, or might he take a moral step back but then continue with his quest for a soul afterwards? He's not willing to do either. Whereas the Little Mermaid has to decide whether to harm her beloved who has hurt her deeply, the Little Merman is urged to kill a mortal enemy who has tried to murder him multiple times. He rejects this partly out of a sense of honor - he has killed dragons but he will not sink to the Regent's level by murdering a human - and partly because he foresees the bloodshed that this kind of war would bring to the whole kingdom. (In the illustrations, the Little Merman wears a crown - possibly of kelp - that looks a little like a crown of thorns.) It's also interesting to contrast the romance with that in The Little Mermaid. Here, the Merman and the Princess are childhood friends. They reconnect as young adults and their relationship deepens. The Merman is inspired by the Princess’s fierce love for her people. He does not have the Little Mermaid’s quest of marrying in order to get a soul; instead he is trying to get a soul so that he can marry the Princess. It’s his concern for her well-being that causes him to reveal his identity and give the chance for her to back out of their mandated engagement, even though it nearly costs him his life. The Little Merman has some fun fish-out-of-water moments and reads as a very peaceful, innocent character. There is a touch of realism in the fact that he gets beat up pretty badly in both dragon-battles and needs a lot of time to recover on both occasions. Meanwhile, the Princess is brave, loyal, and intelligent. She may not ride out to fight the dragons herself, but she’s the one who saves the Merman in the end, using her political savvy and education to delay his trial and build a legal defense. This book is chock-full of folkloric and literary references, and I think I might even prefer its take on souls to that of The Little Mermaid. Bibliography

The story of "The Golden Mermaid" begins with a tree that bears golden apples. This tree grows in the garden of a King who looks forward to the harvest, but the apples begins to go missing just as they ripen. The King, in desperation, orders his two oldest sons to go out and search the world until they find the thief. His third and youngest son begs to be allowed to go too. The King tries to dissuade him, but the prince begs so much that the King relents and sends him off—although with only a lame old horse. On his way through the woods, the prince meets a starved-looking wolf and offers him his horse to eat. The wolf takes him up on the offer, and the prince then asks the wolf to carry him on his back since his horse is gone.

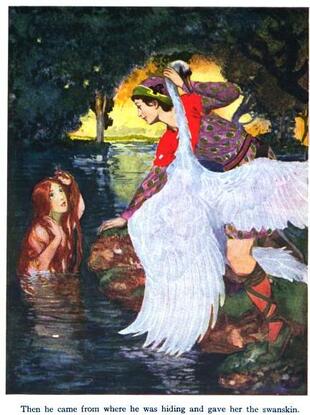

The wolf is actually a powerful, shapeshifting wizard and happens to know who the apple thief is: a golden bird that is the pet of a neighboring emperor and apparently really likes to escape and steal golden apples. He instructs the prince on how to sneak into the palace and steal the bird. However, the prince clumsily slips up and is caught and thrown into the dungeon. The wolf transforms into a king and goes to visit the emperor. He gets the conversation around to the imprisoned prince-thief and tells the emperor that hanging is too good for such a scoundrel; instead he should be sent off on an impossible task to steal a golden horse from the emperor in the next kingdom. At this point, things turn into a chain of fetch quests. The prince sets out weeping bitterly at his misfortune, only to run into the wolf, who encourages him to go in and steal the horse. Everything will be fine! Everything is not fine, and the prince promptly finds himself beaten up and trapped in Emperor #2’s dungeon after getting caught with the golden horse. The wolf wheels out his same trick, and this time the prince is sent off to capture the golden mermaid. The prince reaches the sea, where the wolf helpfully turns into a boat full of silken merchandise to lure the mermaid in. Turns out she doesn’t really mind being captured once she falls in love with the prince. The Emperors, realizing that the prince has obviously had powerful magical help, quickly give up all claim to the golden mermaid, the golden horse, and the golden bird, and the Prince proceeds home with his whole golden entourage. On their way home, the wolf bids the prince farewell. However, the Prince's two older brothers have heard of his success and are bitterly jealous. They ambush and murder their younger brother, and steal the golden horse and bird; however, the brokenhearted mermaid won't go with them and stays weeping over the Prince's dead body. An unspecified amount of time passes, with the mermaid still weeping over the corpse, before the wolf shows up and tells her to cover the body with leaves and flowers. The wolf breathes over the makeshift grave and restores the prince to life. The three return home, the wicked older brothers are banished, and the prince and the golden mermaid get married. “The Golden Mermaid” is a typical example of the ATU tale type 550, “Bird, Horse and Princess.” Another famous example is the Russian story “Tsarevitch Ivan, the Firebird and the Gray Wolf.” Tales of other types can overlap; there’s ATU 301, known as “The Three Stolen Princesses,” and there are swan maiden-esque tales where the golden bird and the maiden are the same entity, as in “The Nine Peahens and the Golden Apples” (from Serbia). The prince is the typical fairy-tale Fool: kind of dumb, but kind-hearted and lucky. We also have the memorable and mysterious wolf magician (helpers in other versions can be foxes, bears or snakes, or sometimes humans under a curse). He's a bit manipulative, but still coaching the clueless prince towards his ultimate success. This character does all the heavy lifting. Shapeshifting into people or inanimate objects? Raising the dead? He’s got it covered. The titular mermaid is probably the most striking thing about this story, but she’s not exactly what modern Western audiences would imagine. She evidently has two legs - see the illustration at the top of this post. This is not so surprising as it might seem; our modern idea of the mermaid with a fish-tail is the result of many years of simplifying and syncretizing and Westernizing. For many cultures around the world, the concept of merpeople - literally, sea-people - could encompass various types of entities and even overlap. And many of those entities would have simply had legs and looked a lot like humans. Think of Greek sea nymphs, the Lady of the Lake and other fairies in Arthurian lore, the Irish tale of the Lady of Gollerus, or "Jullanar of the Sea” in the Thousand and One Nights. Any of these sea people lived in some kind of water realm and could be read as a type of mermaid, yet they don't necessarily have fish tails. This is not the only variant of ATU 550 to include a mermaid; a variant from Slovenia, “Zlata tica” [Golden Bird] features a similar mermaid ("morska deklica") and the trick of catching her attention by selling fine fabric (Janezic, p. 266). The Golden Mermaid has some siren-like attributes, singing and trying to beckon the prince into the water, but fits a lot of feminine stereotypes such as being easily lured with pretty fabric. Still, bear in mind that she's stronger than she might seem to modern readers. In many versions of ATU 550, the heroines are easily carried off by the evil brothers. They continue to weep and can't be comforted, resisting in their own way, but they are as easily stolen as the horse and bird. The golden mermaid is unusual in that she manages to stay with the dead prince and watch over his body. We don't hear how exactly she pulls this off, but she withstands two murderers to do so, something that shouldn't be written off. You may have noticed that in all this, I haven't explained where the story is from. The story appeared in Andrew Lang’s The Green Fairy Book (1892), its most famous and widespread appearance. The Coloured Fairy Book series was published under Andrew Lang's name, but the real minds at work were his wife Nora and a team of mostly female writers and translators. In The Lilac Fairy Book, one of the last few in the long series, Andrew wrote in a preface: "The fairy books have been almost wholly the work of Mrs. Lang, who has translated and adapted them from the French, German, Portuguese, Italian, Spanish, Catalan, and other languages." The problem is that, as sprawling and influential as these books are, the citations are frequently awful. Many sources are cut short or just plain missing. Remember “Hans the Mermaid’s Son,” simply noted as “From the Danish.” And “Prunella,” due to the title change and lack of any source, is cut off from its Italian roots. I had to go hunting to find these stories elsewhere. For “The Golden Mermaid,” there is a single terse editor's note: "Grimm." But "The Golden Mermaid" isn't in the Grimms' collections. This may be one of the worst errors ever in the Colored Fairy Books. It looks like the editor mixed up “The Golden Mermaid” with the Grimms’ “The Golden Bird,” a different version of ATU 550. In “The Golden Bird,” the hero is not a prince but a gardener's son, although he does win the kingdom by the end. He’s a little feistier than The Golden Mermaid’s weepy prince, although still hapless (instead of getting caught through clumsiness or happenstance, he’s tripped up by greed or by being too sympathetic to his enemies). The love interest is not a golden mermaid, but the princess of a golden castle, and the wolf-wizard’s role is filled by a talking fox who is secretly the princess’s long-lost brother under a curse. Some scholars don't catch this and refer to the Grimms' Golden Mermaid anyway. The Penguin Book of Mermaids, published in 2019, notes the misleading source with some consternation and even suggests that Lang wrote “The Golden Mermaid" as a very loose adaptation of "The Golden Bird," placing the story with other literary fairy tales. But “The Golden Mermaid” is actually a folktale. I was lucky to stumble across the real source through a tiny note buried in Wikipedia. It's from Wallachia, a historical region of Romania, and was first published in Walachische Maehrchen (1845) by the German brothers Arthur and Albert Schott with the title "das goldene meermädchen" (p. 253). In Romanian, the title translates to “Fata-de-aur-a-mării"; I'm not sure whether this is a back-formation by later scholars, or if the story has been collected in the original language. Arthur collected these stories during a six-year residency in Banat, and considered “The Golden Mermaid” not only the most beautiful story in the collection, but superior to the German “The Golden Bird.” It’s funny reading both of these stories together, because they occasionally seem to fill in gaps of logic for each other, or you can see spots where a story started to stray from the standard plotline. “The Golden Bird” has a few odd fragments, like a random fourth quest tacked on (moving a mountain in order to win the princess). Overall, "The Golden Mermaid" has some interesting themes and characters to unpack, and I especially enjoyed seeing a mermaid in a tale type where they don't often appear. References

Further reading: other fairytales left without sources by Lang Hi everyone! I'm delighted to announce that my first academic article has been published in Shima Journal. It explores the history of Starbucks' iconic mermaid logo and why Melusine, a serpent-woman from medieval myth, has been identified in recent years with images of double-tailed mermaids. You can read it at 10.21463/shima.190

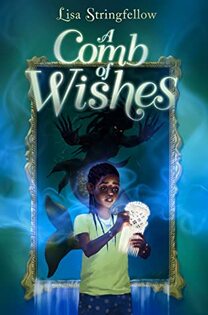

In my list of favorite mermaid books I mentioned A Comb of Wishes, a children's novel released in 2022. I was struck by the many less-popular mermaid motifs that the author, Lisa Stringfellow, wove into the story. There is one story in particular that the plot is built around. As Stringfellow explained, “I wanted my main character to have that trope of making a wish on a mermaid's comb.”

The book revolves around a young girl who finds a mermaid's comb and has the chance to make a wish, but discovers that there is a steep price and mermaids are dangerous, vengeful creatures. Around pages 37-39, she hears the story setting up the background: "The seafolk have been round long before these islands were settled. Coming up out of the water at night, they sit on the rocks and twist their thick hair. Then, they tuck in their combs… One time, an old fisherman came upon a sea woman sitting on a rock in the moonlight. Quick as a flash, she jumped back into the water. But she dropped her comb and the old man picked it up, because he knew it held powerful magic… The old man called out to the sea woman, ‘Mami Wata! Mami Wata!’ And up she come… When the old man showed the sea woman her comb, she asked, ‘What you want from me?’ He said, ‘My wife is sick. I want the power to make her well.’ The sea woman nodded and said, ‘Rake me comb across the water. Then, you throw it back to me. You will have what you want.’ The old man walked into the sea and raked that comb across the water… When he threw it back, the sea woman sank beneath the waves and disappeared. He thought for sure that he had been taken for a fool… But lo and behold!... The old man woke up the next day with his brain full! He knew all types of herbs and healing spells and he was able to make his wife well.” This story has its spark of inspiration in a well-known Cornish tale. "The Old Man of Cury" appeared in Robert Hunt's Popular Romances of the West of England (1865). An old man finds a mermaid trapped in a tidepool, having been distracted by admiring her reflection until the tie went out. She begs him for help and promises him three wishes, so he carries her on his back to the water. He wishes not for wealth, but for the ability to help people by breaking witches' spells, charming away diseases, and the ability to locate stolen goods so he can return them. She agrees and leaves him her comb; from then on, whenever he wants to see her, he can come to the shore and rake it through the water to summon her and she'll teach him the magic and charms he requested. She even offers to take him to her watery realm and make him young again, but he prefers to remain on land. He passes on his magical knowledge to his descendants. A darker and more elaborate version of the story featured in William Bottrell's Traditions and Hearthside Stories of West Cornwall (1870). Bottrell was Hunt's contemporary and one of his most prolific contributors for Popular Romances, but wrote with a much different style, emulating the drolls or storytellers of Cornwall. Bottrell himself was a droll, and his stories are much longer and more detailed. Quite a few stories appear in both Hunt and Bottrell. Bottrell begins the story of "The Mermaid and the Man of Cury" by introducing the storyteller, Uncle Anthony James. Bottrell explains that this was a favorite story and it was often altered "by adding to the story whatever struck his fancy at the moment." Bottrell's version has a similar start as Hunt's, and takes place at the same location. The old man is introduced as Lutey, a fisherman and smuggler. Walking on the shore one day, he hears a woman crying out for help, and discovers a mermaid trapped in a tidepool. Her name is Morvena, or sea-woman. She gives him her comb, which has the power to summon her, and begs him to take her to the sea; she needs to get home, since her abusive mer-husband may eat their children. As he carries her in his arms towards the water, she offers him three wishes. She is pleased by his unselfishness when, rather than requesting money, he asks instead for the ability to help others by breaking witches' spells, commanding spirits, and for these gifts to continue in his family. The mermaid gets flirty and entices him to come down into the ocean with her. He is almost under her siren-like spell when the sound of his dog barking distracts him, and he's able to break free. The mermaid swims away, while promising him that she will return in nine years. Returning home, Lutey discovers that he now has the abilities of healing and wisdom he asked for. Nine years later, while Lutey is fishing with a friend, Morvena returns. Lutey, accepting his fate, goes with her and is never seen again. From then on, every ninth year one of his descendants is always lost to the sea. The story had some popularity. A version probably derived from Hunt's appeared in Arthur Hamilton Norway's Highways and Byways in Devon and Cornwall (1898), and a Bottrell-esque version in "The Sea Maid and the Fisherman" showed up in The Dublin University Magazine in 1871. A version titled "Lutey and the Mermaid" appeared in Mabel Quiller Couch's Cornwall's Wonderland. Couch was specifically retelling Cornish folktales that she'd read, in a simpler style more appropriate for children. Although Couch's version is extremely close to Bottrell's to the point of near-identical descriptions, there are a few lines that make me think she also drew on Hunt. (Hunt: "He thought the girl would drown herself . . . He looked into the water, and, sure enough, he could make out the head and shoulders of a woman, and long hair floating like fine sea-weeds all over the pond, hiding what appeared to him to be a fish's tail." And Couch: "At first Lutey thought she had drowned herself, but when he looked closely into the pool, and contrived to peer through the cloud of hair which floated like fine seaweed all over the top of it, he managed to distinguish a woman's head and shoulders underneath, and looking closer he saw, he was sure, a fish's tail!") In Hunt's version, there's a logic to the mermaid's comb that isn't quite as apparent in Bottrell's version. Hunt's fisherman uses the comb in the act of fulfilling his wish and keeps it as proof. In Bottrell's version, the comb is shown as proof after the encounter but otherwise isn't all that important. It's not clear if Lutey ever uses it to see the mermaid. But all of this is very interwoven. Bottrell may have been the one who gave Hunt “The Old Man of Cury.” Not only do both of their collections feature the story type, but Bottrell notes that he heard many versions of the story from Uncle Anthony. Hunt, in his collection, quotes a letter about Uncle Anthony which may have been from Bottrell. The differences are easily explained by Bottrell’s mention of the way the story changed from telling to telling. (Incidentally, Hunt’s other major contributor was Thomas Quiller-Couch - Mabel Quiller-Couch’s father.) Stringfellow’s reimagining keeps the basics and the ominous sense surrounding mermaids, while weaving it with Caribbean folklore to make a new story. She makes the comb a main focus. The fisherman doesn't just want to help people in general, but has a specific goal of healing his wife - paralleling the main plot, where the protagonist Kela is trying to get her dead mother back. Bibliography

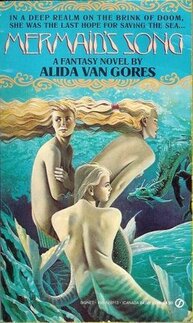

Over the past year or so, I’ve been on the hunt for mermaid fiction. I’ve been through a lot of lists, and here's my own list of some favorites so far. There are many, many, MANY books on mermaids out there. The books here are ones that particularly stood out as both enjoyable and memorable for me this year. Brine and Bone by Kate Stradling (2018): a retelling of The Little Mermaid. Stradling does something I've seen in a few other places by telling the story from the perspective of the other maiden - the human girl who steals the prince's heart. In this version, Magdalena is the prince's childhood friend and the girl he always really loved. What this book does a little differently is that it treats mermaids as fae. This connection often gets lost in modern fiction, but old stories of mermaids and fairies really do overlap a lot. The "little mermaid" is eerie and alien, and the human characters are rightfully fearful of her. But Magdalena surprisingly finds some common ground with the mermaid. My only complaint is that it's pretty short and and I would have liked to see it go even more in depth. Mermaid’s Song by Alida van Gores (1989): In an underwater society torn between two races, the mogs and the oppressed merra, a merra-maid named Elan learns to use her magic and competes for the coveted post of guardian to the Sea-Dragons. The competition will decide the fate of the entire ocean. If you want to read an adult fantasy with a committed treatment of an underwater mermaid world, this is for you. Magic is kept fairly low-key, so the oceanic society feels refreshingly practical, with little details reinforcing that this is not our world - for instance, nobody sleeps in beds, and instead they essentially tie themselves to things. The entire story takes place underwater, which is surprisingly rare for a mermaid book! That said, there were a few uncomfortable themes that kept me from completely enjoying it. For instance, rather than the characters fighting for true equality, the merra are the rightful ruling class and the mogs need to get back to being subservient laborers. All the Murmuring Bones by A. G. Slatter (2021): Mirin O’Malley is one of the last descendants of a formerly prosperous family, whose wealth came from regular human sacrifices to the merfolk. When Mirin’s grandmother plots to marry her off to her creepy cousin and start up the sacrifices again, she runs away to search for her missing parents. Mermaids, rusalki, selkies and other mythical water creatures are more of a backdrop here, ominous figures who haunt Mirin. However, the main plot is interspersed with short, folktale-esque stories that I really enjoyed. I also liked the themes of healing and making amends, and was thoroughly rooting for Mirin by the end. Into the Drowning Deep by Mira Grant (2017): A marine research ship heads out into the ocean to investigate a mysterious disaster and prove whether or not it was caused by mermaids, as rumor has claimed. Turns out the mermaids are all too real - and the research expedition is about to turn into a bloodbath. Despite an underwhelming ending, this B-movie horror in book form is compulsively readable. I just really loved the plot of scientists discovering mermaids. Grant’s faux-scientific patter about mermaids with mimicking abilities and bioluminescent tentacle-hair feels believable, at least to me as someone who knows nothing about marine biology. If that sounds like something you'd enjoy, then this and its prequel, Rolling in the Deep, are both worth a read. The Moon and the Sun by Vonda McIntyre (1997): A dark, dense, intricate historical fantasy where a captured mermaid is brought to the court of the Sun King, Louis XIV. (The mermaids or sea people here have two leg-like tails.) Naive young noblewoman Marie-Josephe learns to understand the "sea monster's" musical speech, sparking an ethical dilemma and a mission to free the imprisoned sea woman. The novel is very much about personhood, touching on misogyny, slavery and treatment of people with disabilities, extending through the image of the sea woman whom authorities are ready to discount as a mindless animal that can be killed and eaten. There’s some good “mermaid” worldbuilding sprinkled in, too; the novel is an expansion of McIntyre's short story, “The Natural History and Extinction of the People of the Sea.” It can be hard to follow at times; there's a huge cast and everyone in the French court has multiple names and titles. (This book got an absolute travesty of a film adaptation, and I’m still mad about it. JUSTICE FOR COUNT LUCIEN!) Emerge by Tobie Easton (2016): Another Little Mermaid retelling - sort of. In this universe, unbeknownst to humans, The Little Mermaid was based on a true story and the heroine’s actions left the undersea world of merfolk in turmoil. In modern times, a mermaid named Lia Nautilus lives in disguise as a human, shielded from the war going on in the deep. When she learns that her human crush is in danger, she turns to forbidden siren magic to save him. This cheesy, fluffy teen romance, the first of a series, was a surprise favorite for me. I was initially put off by the cartoony worldbuilding and puns (in one early eyerolly moment, a hot guy is called a “total foxfish”). But Easton commits to it and clearly put a lot of thought into a world with shapeshifting mermaids, underwater architecture, and magic. Lia’s plight is compelling, and I found myself enjoying the trilogy even more as it went on. A Comb of Wishes by Lisa Stringfellow (2022): Kela, a young girl grieving her mother’s death, finds a mermaid’s comb. The mermaid offers her a wish in exchange for its return, and there’s only one real option for Kela: for her mother to be alive again. But there’s a steep price for wishes, and when the comb is stolen before Kela can return it, things quickly start to go wrong. This middle-grade novel was a joy to read. Stringfellow blends the Caribbean setting with touches of mermaid stories from around the world (from "The Little Mermaid" to "The Old Man of Cury" and "The Soul Cages"). Mermaids are more of a mystical force here than in most of the other books on this list, but this book is firing on all cylinders with lyrical writing and a compelling, emotional plot. Some of these books I honestly didn't expect to like so much - I originally ignored Emerge because of the punniness, A Comb of Wishes because it was a kids' book, All the Murmuring Bones because it sounded like the mermaids were barely in it. It was exciting to be able to add them to the list. Looking at this list, I realize that most of them are set primarily on land or have human main characters; this is a common theme. Writing an underwater setting can be a challenge because it rules out so much of society and technology that we take for granted.

I'll continue to read mermaid books as I find them - because I like mermaids, but it's also fun to observe the popular image of these beings from folk and fairy tales. The Little Mermaid is a very popular subject for retellings. If you have a favorite mermaid book, drop it in the comments! Today I want to talk about a little corner of overlapping folktales. These stories follow a young woman who, out of lust or greed or maybe just foolhardiness, is enticed to open a gate and allow enemy forces into her home. Her home is destroyed and she meets an ironic death. Also, there's a connection to myths of mermaids and flooded cities.

A basic traitorous-daughter story, without the floods and mermaids, is the legend of Tarpeia, the daughter of the Roman commander at a time when Rome was under siege by the Sabines. Tarpeia secretly offered the Sabine leader a deal - she'd let his soldiers inside in exchange for what they bore on their left arms. She thought she was making a deal for their precious golden bracelets. However, when she opened the gate and waited eagerly for her reward, the Sabine soldiers instead threw their left-handed shields onto her and she was crushed to death. Arthur A. Wachsler made a connection from this and similar tales to Aarne-Thompson type 313, "The Girl as Helper in the Hero's Flight." In both cases we have a female character who betrays her father for the sake of a male outsider whom she helps on a mission. However, this doesn't quite work. The fairytale - and even mythical parallels such as Medea and Ariadne - are focused on the adventures of the hero, and the girl is at least initially a heroic figure who winds up abandoned and forgotten for her troubles. (The fairytale version gets her man back.) Tarpeia-style tales are harsher parables in which the girl is both villainous and foolish, and promptly gets herself killed. A specific strand of these more moralizing tales include a theme of water and transformation. I have found three examples so far: Scylla of Megara, Dahut, and Lí Ban. Scylla of Megara: from Ovid's Metamorphoses The guarded city: The city of Alcathous, ruled by King Nisus, is under attack by King Minos. However, Nisus has a lock of purple hair that makes him invincible. Opening the gate: Nisus's daughter, Scylla, sees Minos from afar and falls madly in love with him. That night, she sneaks into her father's bedroom and cuts off the purple lock, destroying his gift of invulnerability. She then sneaks out of the city and goes to Minos's war camp, where she presents him with the hair (and maybe even her father's head). Disturbed, Minos immediately leaves in his ship. Immersion and transformation: Scylla leaps into the sea after Minos and tries to climb onto the ship. Her father, who has transformed into an eagle, attacks her. As she falls from the ship, she is transformed into a sea bird or ciris. It's important that Scylla's flight and transformation take place on the sea. Also, although there's no direct connection between the characters, note that the most famous Scylla of classical mythology was a sea monster. Dahut of Ys: from Brittany The guarded city: King Gradlon rules the city of Ys. The city is shielded from floods by a dike, and Gradlon alone holds the key to the sluice gate. Opening the gate: Gradlon’s daughter, Dahut or Ahes, is a wicked, unchaste young woman. One night, while meeting with her lover (who in some versions is the actual Devil), she steals her father's key and opens the sluice gate. Immersion and transformation: Gradlon wakes up to find the city flooding. He and Dahut flee on his horse, but the waves are about to overtake them. Gradlon throws Dahut off his horse, and as soon as she falls into the water, the flood stops. The city of Ys is lost but can sometimes still be seen beneath the waves, and Dahut becomes a Mari-Morgan (Breton for mermaid) and people often hear her singing. (Jean-Michel Le Bot points out that "mari-morgan" is also a term for monkfish (Lophius piscatorius) in some areas of Brittany.) The earliest accounts of Ys do not mention Dahut, whose first known appearance was in 17th-century monk Albert Le Grand's Vies des Saints de la Bretagne Armorique. This first mention is pretty brief, with Dahut dying. Subsequent versions fleshed out more details, and the modern version of the tale is highly literary. Matthieu Boyd has a good rundown of the evolution of the story, including recent retellings which make Dahut a heroic figure. Amy Varin makes a shaky argument that Dahut was originally a sovereign goddess who bestowed kingship on her chosen consort (most of her evidence is unrelated legends of mermaids or otherworldly maidens who married humans). Lí Ban: from Ireland The guarded city: A man named Eochaid comes to a place with a spring well. He builds a house there, and sets a woman to tend the well so it doesn't overflow. Opening the gate: One day, the woman fails to cover the well. Immersion and transformation: This causes a flood which creates the lake known as Lough Neagh, drowning Eochaid and all of his children except for two sons and Lí Ban. Lí Ban survives in her chamber underwater and is transformed into a salmon or, in some versions, a mermaid. Centuries later, she encounters monks and tells them her story. She receives the name Muirghein. The parallels from Lí Ban to Dahut are fainter, but there are indications that these stories share some root. The cognate name Morgan/Muirghein is particularly striking. Amy Varin suggests that - based on the parallels in story structure - Lí Ban herself is the woman who fails to cover the well. Compare another variant of Lough Neagh's origin, recorded by Giraldus Cambrensis in the Topography of Ireland. “Now there was a common proverb . . . in the mouths of the tribe, that whenever the well-spring of that country was left uncovered (for out of reverence shown to it, from a barbarous superstition, the spring was kept covered and sealed), it would immediately overflow and inundate the whole province, drowning and destroying the whole population. It happened, however, on some occasion that a young woman, who had come to the spring to draw water, after filling her pitcher, but before she had closed the well, ran in great haste to her little boy, whom she had heard crying at a spot not far from the spring where she had left him. But the voice of the people is the voice of God; and on her way back she met such a flood of water from the spring that it swept off her and the boy, and the inundation was so violent that they both, and the whole tribe, with their cattle, were drowned in an hour in this partial and local deluge. The waters, having covered the whole surface of that fertile district, were converted into a permanent lake. A not improbable confirmation of this occurrence is found in the fact that the fishermen in that lake see distinctly under the water, in calm weather, ecclesiastical towers . . . and they frequently point them out to strangers travelling through these parts, who wonder what could have caused such a catastrophe.” (Spence, p. 188) This type of flood myth is common and a few Celtic variants stand out as caused by a woman. In a Scottish story, the ancient witch known as the Cailleach had a well in Inverness which needed to be kept covered at night. She tasked her maid, Nessa, with caring for the well. But one evening, Nessa was late to cover it, and by the time she got there, water was flooding from the well. Nessa ran away, but the Cailleach - watching from a mountain - cursed her never to leave the water, and Nessa was transformed into the River Ness (connected to the Loch Ness). Every year on the anniversary, Nessa briefly appears in human form to sing sadly. (There is a similar tale of the River Boyne, where the flood is caused by an "attendant nymph" who foolishly walks withershins three times around the well.) (Hull, 249-250). Sir John Rhys collected some stories of Glasfryn Lake, which he identifies as a Welsh "Undine or Liban story". A woman named Grassi, or Grace, committed the same misstep of leaving a well uncovered and causing a flood. Grassi either became a weeping ghost haunting the field by the newly made lake, or was transformed into a swan by fairies. Rhys also noted that the Glasfryn family had a mermaid on their coat of arms, and theorized that the well maiden was originally named Morgen or Morien, to fit with the Lí Ban model. One of the oldest parallels is the Welsh story of the drowned city Cantre'r Gwaelod, dating to the 13th-century Black Book of Camarthen . . . maybe. The problem here is that the original poem has been translated in many contradictory ways. Some translations place the blame on Mererid, a well maiden who neglected her duties. Other translations state that the culprit was Seithennin, a male drunkard who failed to close the sluices. Or it was both Mererid and Seithennin. Or maybe neither of these are characters in the first place, and we’re looking at generic nouns which have been misread as names. We don't know! (Celtic Review, pp. 338-340) Overall, in general there are two distinct stories.

You might even go back as far as the Assyrian myth of Derceto or Atargatis. In Diodorus Siculus’s rendition of the story, the goddess Derceto offended Aphrodite, who retaliated by making her fall for a certain young man. Derceto had sex with him and gave birth to a child, but was ashamed. To hide what she’d done, she murdered her lover and abandoned the baby. Finally, she flung herself into a lake, where she was transformed into a fish with a human head. It doesn’t map onto the story exactly, but here we do have a woman who falls into lust (like Scylla and Dahut), commits a betrayal, and instead of drowning meets a watery transformation. Dahut is a particularly interesting case. She may not have originally been part of the story of Ys. Was the well maiden motif added later to the story of King Gradlon and his flooded city? And could John Rhys be right that the original name of this figure was something like Morgan, "sea-born"? Sources

“Ondine’s Curse” is the name of a rare form of apnea, a condition in which people stop breathing. According to various medical texts, it's based on an old Germanic legend - the story of Undine or Ondine, who cursed her faithless lover to stop breathing. Except . . . this doesn't sound anything like the story of Undine, which isn't even exactly a legend. What's going on here?

The Backstory As I've described before on this blog, "undines" originally came from the writings of 16th-century philosopher Paracelsus. The word was evidently his original creation, referring to water elementals or nymphs. Combining the medieval legends of "Melusine," "Peter von Stauffenberg," and various folktales about fairy wives, Paracelsus wrote that undines could gain a soul by marrying a human. However, such relationships were fraught with danger; these water-wives could all too easily be lost to the realm they'd come from, and if the mortal husband took another wife, the water-wife would come back to murder him. This story was passed around and adapted by various authors. Most famously, it found form in the 19th-century novella Undine by Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué. Undine is a nymph who marries the knight Huldbrand and gains a soul as a result. However, he ditches her for a human lover - which, by the rules of spirits and the otherworld, means he must die. Although Undine still loves him, she is forced to kill him on the night of his second wedding. She appears and embraces him, weeping. "Tears rushed into the knight's eyes, and seemed to surge through his heaving breast, till at length his breathing ceased, and he fell softly back from the beautiful arms of Undine, upon the pillows of his couch—a corpse." Undine then states mournfully, "I have wept him to death." So where did things go off track? This novella became extremely popular, inspiring many adaptations. There were plays, operas, ballets. Even Hans Christian Andersen's The Little Mermaid took inspiration from it. One play adaptation, Ondine, by Jean Giraudoux, came out in 1938. In this version, the characters are named Ondine and Hans. Although Hans betrays Ondine with another woman, she still loves him and attempts to stop her people from executing him by running away. However, her efforts are of no avail, and Hans is condemned to death by the king of the water spirits. The former lovers get the chance to say goodbye. The tormented Hans tells Ondine, “Since you went away, I've had to force my body to do things it should do automatically. I no longer see unless I order my eyes to see... I have to control five senses, thirty muscles, even my bones; it's an exhausting stewardship. A moment of inattention, and I will forget to hear, to breathe... He died, they will say, because he got tired of breathing..." As the two share a final kiss, Hans dies and Ondine's memories of him are erased. Losing the Way In 1962, a California-based doctor named John Severinghaus and his colleague Robert Mitchell worked with three patients who all shared similar symptoms. After operations on the brain stem, these patients could not breathe automatically. They had to consciously decide to breathe, and they needed artificial respiration when asleep. Severinghaus and Mitchell wrote a paper about their studies, coining the term "Ondine's Curse" for the phenomenon. They stated briefly: "The syndrome was first described in German legend. The water nymph, Ondine, having been jilted by her mortal husband, took from him all automatic functions, requiring him to remember to breathe. When he finally fell asleep, he died." This is a garbled version of Giraudoux's play. They were clearly inspired by Hans's speech, and as pointed out by researcher Fernando Navarro, they use Giraudoux's spelling, "Ondine." But you can see the play being misunderstood and slanted here, misremembered just a little. Their summary was soon picked up, gaining a life of its own as other medical professionals repeated and mangled it further. Many versions simply repeat some variation on Severinghaus and Mitchell, but we see an emerging image of Ondine as a forceful figure who delivers judgment on her traitorous husband. She, not the ruler of the water spirits, curses Hans. Across various versions, she is angry, a purveyor of revenge or punishment (Navarro 1997). Usually the husband or lover is unnamed, but Hans remains a common moniker (as in Naughton 2006). Some retellings get much more elaborate, with their own mythology. A popular variant explains that if a nymph ever falls in love with a mortal and gives birth to his child, then she will become an ordinary mortal, subject to aging. Nevertheless, the nymph Ondine falls in love with a human, and he with her. One version names him Lawrence (Coren 1997); another calls him Palemon, borrowing from Frederick Ashton's 1958 ballet adaptation Ondine (Mawer 2009). Lawrence/Palemon/whoever swears to her that “My every waking breath shall be my pledge of love and faithfulness to you." However, after she bears his son, Ondine begins to age, and her beauty fades. Her shallow husband dallies with other women. When Ondine catches him in bed with a mistress, she is enraged. With the last of her magic, she calls down a curse which mocks her husband's broken vow: as soon as he falls asleep, he'll stop breathing. Her husband inevitably falls asleep from exhaustion and dies. This variant upends the original worldbuilding. In Fouque’s novel, marriage grants Undine a soul, but she remains otherworldly and powerful. Huldbrand rejects her out of fear and resentment. However, in this variant, marriage transforms Ondine into an ordinary woman, and that's why her husband strays. Some of the shorter retellings are so clumsily phrased that they mix up vital information. One skips over the husband's infidelity: "[T]he beautiful water nymph . . . punished her mortal husband by depriving him of the ability to breathe automatically. Without the benefit of tracheostomy, the poor wretch, having forgotten how to breathe, died in his sleep." (Vaisrub 1978) Another makes Ondine the cheater in the situation! "Ondine, a German water nymph, invoked a curse upon her jilted husband so that he would forget to breathe (and die) when he fell asleep." (Swift 1976, as cited in Navarro 1997) Or was Ondine the one who was cursed? "[T]he water nymph Ondine was punished by the gods after falling in love with a knight by being condemned to stay awake in order to breathe." (BBC 2003) In some versions, Ondine is a succubus-like serial killer: "...a water-spirit of German mythology called Ondine who could cause the death of her victims by stopping their respiration." (Taitz et al 1971, as cited in Navarro 1997) "Ondine was a mythological water nymph who exhausted her human lovers." This author quotes Giraudoux's play, but labels Hans as just "one victim"! (Sege 1992) And sometimes the nature of the curse itself changes to a perpetual sleep, as in one dictionary where Ondine is "A water nymph who caused a human male who loved her to sleep forever." (Firkin 1996) The story goes completely off the rails in one article on spine surgery: "Ondine, a shepherd in Greek mythology, was cursed for his misdeeds by being put into a sleep from which there was no awakening." (Fielding et al, 1975, as cited in Navarro 1997) Critics were rightfully outraged at this summary, which manages to get every single detail wrong. The writers were following blindly in the footsteps of a very confused 1968 article which evidently mixed up Undine with the Greek myth of Endymion. The mistake is so wildly far off that I'm honestly impressed. Conclusion This is what happens when a bunch of people start retelling a story they've never read. The heart of the modern character Undine – carrying through to her spiritual successor, the Little Mermaid – is that she loves her husband. Her love is self-sacrificing and all-forgiving. The medical myth around “Ondine’s Curse” inverts this, making her a vindictive wife, a vampiric seductress, or a sheep-tending Greek man. One article examines the history but concludes lackadaisically, "Whether Ondine kissed or clasped her husband to death depends on the version of the tale, and one can never know who cursed whom" (Tamarin et al, 1989). That's not true, though! This isn't like traditional oral folktales where there really are multiple unique variants and no one can determine an original. This is more like saying that we can never really know whether Dorothy's slippers were silver or ruby in The Wizard of Oz. At what point does urban legend or commonly-repeated misconception become folklore? Can Ondine be considered a myth or legend, as it is often called? Perhaps it has become something of an oral folktale in the medical community. But given that it came specifically from literature, I hesitate to call it that. This is part of a larger issue surrounding the story of Undine. It left its stamp on Western culture, but the work itself has become pretty obscure. For instance, many readers take jabs at Hans Christian Andersen for the theme of souls and salvation in The Little Mermaid, calling it tacked-on or a case of preachy Christian moralizing. But that plotline wasn’t original to Andersen – it was his response to Undine. Scholars such as Oscar Sugar, Ravindra Nannapaneni, and Fernando Navarro have put significant work into tracing the fragmented and confused medical legend of Ondine's Curse. Many of them have argued against using the name at all, calling it a misnomer. From the other side, psychology professor Stanley Coren complained that the term was losing favor because of political correctness and "language sensitivity, where labeling people as suffering from some form of curse is seen as being insensitive rather than colorful." However, Coren says this right after weaving an elaborate summary which bears almost no resemblance to the real story. He also incorrectly attributes the coining of the term to the 1950s. And the vast majority of critics don't complain that it's mean to call a medical syndrome a curse; instead they focus on the fact that the name is fundamentally a bad fit. On the literary level, Ondine neither causes the "curse" nor experiences it, and Hans's experience goes way beyond apnea. You could get pedantic and say "Well, it's named after the play, not the character" but clearly it has not been taken that way. On the medical level, the shifting definitions lead to inconsistency on what the medical condition is. As Nannapaneni et al point out, the name "Ondine's Curse" has come to be used inconsistently for all sorts of conditions related to respiration. Not ideal for a medical term. They suggest that “this wide and nonspecific usage reflects a lack of awareness of the origins of this eponymous term.” These days, the condition is typically known as Congenital Central Hypoventilation Syndrome (CCHS); however, the name "Ondine's Curse" is still around in casual language, and is apparently here to stay. References

Other Blog Posts "Swan Lake" and "The Little Mermaid" are the same story.

But wait, you may say. The Little Mermaid is a Danish fairytale by Hans Christian Andersen about a mermaid. Swan Lake is a Russian ballet by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, about a princess turned into a swan by a curse. In fact, both stories take inspiration from the Fairy Bride or “Quest for the Lost Bride” tale, categorized as Aarne-Thompson-Uther 400. In the Fairy Bride tale, a man takes an otherworldly creature as a wife. They live together for a while, possibly having children, but one day she leaves him and returns to her own world. This is similar to stories with a mortal woman and supernatural husband, like "Cupid and Psyche" or "East o’ the Sun and West o’ the Moon." However, while human brides usually get their supernatural husbands back, in ATU 400 - despite the title of "The Quest for the Lost Bride" - it’s less certain that a mortal husband will succeed. Many versions end with him never seeing his fairy wife again. The earliest known example is the Hindu story of Urvasi, found in the Rig Veda (c. 1200 B.C.E.). There are different types of the Fairy Bride story: A) It’s a story of spousal abduction. A man discovers a beautiful maiden - a selkie or swan maiden with a removable animal skin, or a mermaid with a magic cap. He hides the magical garment, trapping her in human form. She inevitably regains the garment and escapes as fast as she can. B) The marriage is consensual, but there is some taboo the husband must not violate (never strike his wife, never spy on her while she’s bathing, etc.). He invariably violates it, and she leaves. The most famous example is Melusine, first appearing in the Roman de Melusine by Jean d'Arras (1393). She marries a man and their union is happy at first; she builds castles for him and bears many sons. But she makes him promise never to look in at her while she's bathing. Inevitably he does so, and sees her as a half-serpent or a mermaid. When he publicly calls her a serpent, she turns into a dragon and flies away. In many versions the idea is that if he had kept his promise, she would have been freed from her curse. There's a related folktale where a young man encounters a woman who's been turned into a serpent or half-serpent by a curse. If he can kiss her three times, she will be freed and he will receive riches and her hand in marriage. Before he can kiss her a third time, he is overcome by fear and runs away. He soon regrets his cowardice, but is never able to find her again. In fact, in some versions this woman is Melusine. The maiden-turned-serpent freed by a kiss appears in many medieval sources. The story gets a tragic, inconclusive ending in The Travels of Sir John Mandeville (14th century) but a happy ending in the French romance Le Bel Inconnu (12th century) and Italian Carduino (14th century). The gender-swapped version would be the medieval story of The Knight of the Swan (tragic ending). In a further variant of B, the taboo is taking another wife. This appeared most prominently in the medieval poem of Peter von Staufenberg (c.1310). Peter's nymph mistress showers him with good fortune but gives him one condition: he must never marry anyone else, or he'll die three days after the wedding. However, other people put pressure on Peter to marry a human woman, with many telling him the nymph is a demon, and he eventually gives in. At his wedding feast, the nymph's leg appears through the ceiling. Three days later, Peter dies. The later story "Melusine im Stollenwald" combines this with Melusine and the Serpent Maiden tales; a man named Sebald promises to kiss Melusine three times to break her curse, but she becomes progressively more serpentine and dragon-like, and his courage fails him. Years later, at his wedding feast to another woman, the ceiling cracks and a drop of poison falls unseen onto Sebald's food. He eats it and dies. A snake tail is seen through the ceiling, implying that the poison is Melusine's venom. Paracelsus, a Swiss philosopher, worked both Melusine's and Peter von Staufenberg's tales into his descriptions of elemental beings in A Book on Nymphs, Sylphs, Pygmies, and Salamanders, and on the Other Spirits (published in 1566). He dubbed the water elementals "undines." German author Friedrich de la Motte Fouque spun this into a novella, Undine, published in 1811. There's another work that probably inspired Fouque: the successful Viennese play Das Donauweibchen (1798), which follows a knight named Albrecht torn between his mortal wife Bertha and water nymph lover Hulda. The plot is very different from Undine, but the love triangle, setting, and names are similar. Fouque's plot runs as follows: Boy meets water-fairy. A knight named Huldbrand goes traveling through the woods, where he meets and falls in love with the mysterious Undine. It turns out that she’s a water-spirit, and she gains a human soul by marrying him. The fidelity test. Fouque uses two taboos, straight from Paracelsus: first, the husband must never scold his nymph wife near the water or she’ll return to her own world, and second, if he ever takes another wife, the nymph will return and kill him. The doppelganger. Huldbrand reconnects with his first love Bertalda. Bertalda is, in a way, Undine's sister; she’s the long-lost daughter of Undine’s human foster parents. The tragic ending. Huldbrand breaks the first taboo by bringing up Undine's inhuman origins and berating her, causing her to disappear. He then breaks the second taboo by marrying Bertalda. Undine appears after the wedding and drowns him with her tears. When he is buried, she becomes a fountain flowing around his grave. Now we come back to "The Little Mermaid" and "Swan Lake." These stories map onto the same points as Undine. The Little Mermaid We know from Hans Christian Andersen’s letters that he was inspired by Undine when he developed the concept for “The Little Mermaid” (1837). Like Undine, the mermaid is motivated by her desire for a soul. It hits generally the same beats as Fouque's novel: Boy meets water-fairy. The mermaid saves a prince's life and falls for him. The fidelity test. The mermaid can earn a soul by marrying the prince, but if he marries someone else, she will die. The doppelganger. The prince mistakenly attributes his rescue to a human girl who physically resembles the mermaid. The tragic ending. The prince marries the other girl. On the wedding night, the mermaid is given the option to escape death by killing him. She refuses and melts into sea foam, but is resurrected as an air spirit. Swan Lake Around 1870, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky worked on an unsuccessful opera version of Undine. He destroyed most of the score, but recycled part of Undine and Huldbrand’s duet for the music of "Swan Lake," which debuted in 1877. It didn't initially do well, but in 1895 it was brought back and reworked with a simpler plot. Tchaikovsky died shortly before the new version could be completed. Boy meets water-fairy. In the 1877 version, Prince Siegfried hunts some swans until they reach a lake. There he discovers that they are fairy maidens in disguise. Odette, the leader, is the daughter of a knight and a fairy, and is in hiding from her murderous stepmother. Her grandfather, a sorcerer, gave her a magic crown to protect her, and allows her to fly freely in swan form at night. (In the updated 1895 version, Odette and her companions are humans transformed into swans by the evil genie Rothbart - a minor character in the original.) The fidelity test. Marriage will permanently protect Odette from her stepmother. Siegfried promises to marry her. (1895: Siegfried’s oath of love to Odette will break the curse, but if he marries someone else, he dooms her to remain a swan forever.) The doppelganger. Rothbart's daughter Odile, a girl who looks physically identical to Odette (played by the same ballerina). The tragic ending. Siegfried is tricked into proposing to Odile, betraying Odette in the process. Realizing his mistake, he runs back to the lake, where he tears off Odette's crown in an attempt to keep her with him. She dies in his arms and the lake swallows them both. (1895: Instead of the crown scene, Siegfried and Odette drown themselves rather than live without each other. This breaks Rothbart's power.) Inspirations and Themes Swan Lake and The Little Mermaid are not adaptations of the Undine story. They are unique works by modern authors, and Undine was just one of many inspirations behind them. Andersen was familiar with many mermaid stories. "The Little Mermaid" is unusual among the tales listed in this post, because it's entirely from the "fairy bride's" point of view. Her backstory, her feelings about immortal souls, her journey. Unlike Undine or Odette, who depend on their men to complete a test, she bears the knowledge of her test alone; her prince never has any idea what's really going on. The ending of her story, where she refuses to kill the prince, is an intentional reversal of Undine (and, in turn, "Peter von Staufenberg"). Undine easily gains an immortal soul but is still forced to obey her deadly otherworldly nature. The Little Mermaid earns a soul by rejecting that side of herself no matter the cost. "Swan Lake," on the other hand, combines Undine with the traditional swan wife folktale. There are plenty of theories about Tchaikovsky's inspirations, and plenty of European swan-shifter myths. There's the Irish story of the Children of Lir, where the main characters are transformed into swans by their wicked stepmother, and similarly "The Knight of the Swan" which, as already mentioned, has its own similarities to Melusine. (When I first started working on this blog post, the Wikipedia page for Swan Lake claimed that a fairytale called "The White Duck" could have inspired the ballet; however, the stories have nothing in common. I'm not sure where this claim came from and it's been removed anyway at this point, but I wanted to document it for posterity.) A likely influence is Johann Karl August Musäus's 1782 novella "Der geraubte Schleier" or "The Stolen Veil," itself a retelling of the swan maiden folktale. The main character, Friedbert, encounters a hermit named Benno. (“Benno” is the name of Siegfried’s best friend in Swan Lake.) The dying hermit shows him a magical pool, visited occasionally by fairies or nymphs in swan form. The nymphs gain their powers of transformation from golden crowns with attached veils. If a nymph’s crown/veil is stolen, she’ll be trapped in human form. Benno the creepy stalker hermit failed, but Friedbert succeeds in stealing one of the veils. He gives shelter to the stranded swan maiden, Callista, and convinces her to marry him. But when his mother unwittingly exposes his lies and returns the veil, Callista is furious and immediately takes off in swan form. Friedbert searches across the world until he finds her again. Despite her initial anger, she still loves him, and is so impressed by his tireless search for her that she forgives everything. So this is why Siegfried rips off Odette's crown in the original ballet - he is trying to invoke the trope that you can capture a swan maiden by taking her garment. However, Odette's crown was actually protecting both of them. Although it was later edited out, Tchaikovky's twist feels almost like a rebuttal of the way "The Stolen Veil" rewards Friedbert's selfishness. Tchaikovsky was probably also familiar with Russian fairy tales about swans. A different tale type, ATU 313 or "Girl Helps the Hero Flee," often has overlap with swan maiden tales. One example that Tchaikovsky could have encountered was "The Sea Tsar and Vasilissa the Wise" in Alexander Afanasyev's collection of Russian tales, published in the 1850s and 1860s. In this story, a prince spots the Sea Tsar's daughters as they transform from spoonbills into women. He steals the clothing of one princess, Vasilissa; however, unlike the typical fairy bride story, he relents and returns it to her, letting her fly away. Vasilissa later aids him with various magical tasks when he is imprisoned by her father. The Sea Tsar finally allows the prince to choose a bride from among his twelve identical daughters, and Vasilissa leaves clues for the prince to recognize her. Reunited, the prince and Vasilissa return to his kingdom together. In some versions, the prince then breaks a taboo and gets amnesia, and Vasilissa must crash his wedding to another woman so she can trigger his memories. The plot is very different, but notice the (double!) threat of the prince mistakenly marrying a doppelganger. Conclusion Abduction variants of the Fairy Bride tale are about control. Marriages are thinly disguised kidnappings; wives are captives who will take any opportunity to escape. On the other hand, consensual variants are about a test of trust, commitment, or courage. If the male partner passes this test, he can lift the fairy bride to a higher state of existence. Freedom from a curse for Odette, Melusine or the serpent-maiden; a human soul for Undine and the Little Mermaid. It's not a one-and-done test, either; it is long-term. The serpent maiden needs repeated kisses. Undine gets her soul early on, but Huldbrand still needs to continuously honor their vows and be a good husband. Researcher and professor Serinity Young found that the earliest recorded fairy bride stories are of divine women who lift their mortal husbands to a higher state of existence. For instance, the celestial maiden Urvasi promises her husband immortality in heaven. Young proposes that the fairy bride story in its oldest form was about marriage by abduction; Urvasi tells her mortal husband that she was miserable in their marriage, and other early versions similarly focus on the fairy bride's unhappiness and feelings of being trapped. Young suggests that as women lost social status, fairy bride stories were recast in more romantic terms. I wonder if they also blended with a separate story tradition of a cursed beast-bride or snake maiden. In addition to making the male character more sympathetic, the romantic versions also reverse the power dynamic. The mortal man is now the one holding redemptive, transformative power. This culminates in the extreme of "The Little Mermaid," written in a modern Christian European context. The Mermaid is the pursuer in her relationship, going through incredible suffering on her quest, while the prince rejects her as a romantic partner. She is the one seeking both marriage and immortality. However, despite these changes, the mortal man’s fallible nature remains from the older stories. The love rival twist is especially interesting to me. Peter von Staufenberg and Huldbrand bend to societal pressure by marrying human women, taking the easy way out. Swan Lake's Siegfried and the Little Mermaid's prince have a different dilemma. Despite good intentions, they look only at the surface, failing to truly perceive the women they love. SOURCES

Other Blog Posts I recently came across an article by Lauren and Alan Dundes stating that Hans Christian Andersen used two famous motifs in his fairytale “The Little Mermaid.” First is the motif of mermaids which, yeah. But second is ATU K1911, “The False Bride.” The authors state that "This second motif, though critical for an understanding of the plot of 'The Little Mermaid' has not received much attention” (56). This article gets more into Freudian analysis, which is not really my thing, but I was really intrigued by the connection from the False Bride motif to The Little Mermaid.