|

The story of "The Golden Mermaid" begins with a tree that bears golden apples. This tree grows in the garden of a King who looks forward to the harvest, but the apples begins to go missing just as they ripen. The King, in desperation, orders his two oldest sons to go out and search the world until they find the thief. His third and youngest son begs to be allowed to go too. The King tries to dissuade him, but the prince begs so much that the King relents and sends him off—although with only a lame old horse. On his way through the woods, the prince meets a starved-looking wolf and offers him his horse to eat. The wolf takes him up on the offer, and the prince then asks the wolf to carry him on his back since his horse is gone.

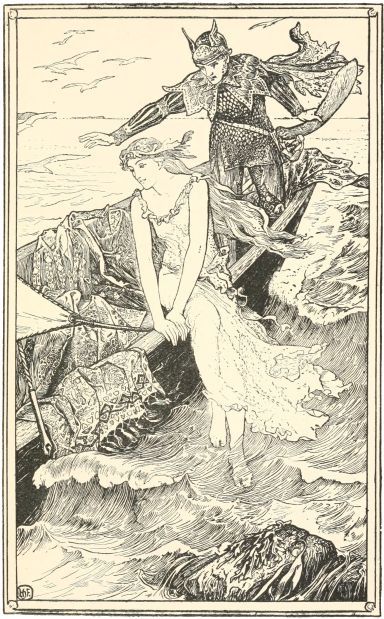

The wolf is actually a powerful, shapeshifting wizard and happens to know who the apple thief is: a golden bird that is the pet of a neighboring emperor and apparently really likes to escape and steal golden apples. He instructs the prince on how to sneak into the palace and steal the bird. However, the prince clumsily slips up and is caught and thrown into the dungeon. The wolf transforms into a king and goes to visit the emperor. He gets the conversation around to the imprisoned prince-thief and tells the emperor that hanging is too good for such a scoundrel; instead he should be sent off on an impossible task to steal a golden horse from the emperor in the next kingdom. At this point, things turn into a chain of fetch quests. The prince sets out weeping bitterly at his misfortune, only to run into the wolf, who encourages him to go in and steal the horse. Everything will be fine! Everything is not fine, and the prince promptly finds himself beaten up and trapped in Emperor #2’s dungeon after getting caught with the golden horse. The wolf wheels out his same trick, and this time the prince is sent off to capture the golden mermaid. The prince reaches the sea, where the wolf helpfully turns into a boat full of silken merchandise to lure the mermaid in. Turns out she doesn’t really mind being captured once she falls in love with the prince. The Emperors, realizing that the prince has obviously had powerful magical help, quickly give up all claim to the golden mermaid, the golden horse, and the golden bird, and the Prince proceeds home with his whole golden entourage. On their way home, the wolf bids the prince farewell. However, the Prince's two older brothers have heard of his success and are bitterly jealous. They ambush and murder their younger brother, and steal the golden horse and bird; however, the brokenhearted mermaid won't go with them and stays weeping over the Prince's dead body. An unspecified amount of time passes, with the mermaid still weeping over the corpse, before the wolf shows up and tells her to cover the body with leaves and flowers. The wolf breathes over the makeshift grave and restores the prince to life. The three return home, the wicked older brothers are banished, and the prince and the golden mermaid get married. “The Golden Mermaid” is a typical example of the ATU tale type 550, “Bird, Horse and Princess.” Another famous example is the Russian story “Tsarevitch Ivan, the Firebird and the Gray Wolf.” Tales of other types can overlap; there’s ATU 301, known as “The Three Stolen Princesses,” and there are swan maiden-esque tales where the golden bird and the maiden are the same entity, as in “The Nine Peahens and the Golden Apples” (from Serbia). The prince is the typical fairy-tale Fool: kind of dumb, but kind-hearted and lucky. We also have the memorable and mysterious wolf magician (helpers in other versions can be foxes, bears or snakes, or sometimes humans under a curse). He's a bit manipulative, but still coaching the clueless prince towards his ultimate success. This character does all the heavy lifting. Shapeshifting into people or inanimate objects? Raising the dead? He’s got it covered. The titular mermaid is probably the most striking thing about this story, but she’s not exactly what modern Western audiences would imagine. She evidently has two legs - see the illustration at the top of this post. This is not so surprising as it might seem; our modern idea of the mermaid with a fish-tail is the result of many years of simplifying and syncretizing and Westernizing. For many cultures around the world, the concept of merpeople - literally, sea-people - could encompass various types of entities and even overlap. And many of those entities would have simply had legs and looked a lot like humans. Think of Greek sea nymphs, the Lady of the Lake and other fairies in Arthurian lore, the Irish tale of the Lady of Gollerus, or "Jullanar of the Sea” in the Thousand and One Nights. Any of these sea people lived in some kind of water realm and could be read as a type of mermaid, yet they don't necessarily have fish tails. This is not the only variant of ATU 550 to include a mermaid; a variant from Slovenia, “Zlata tica” [Golden Bird] features a similar mermaid ("morska deklica") and the trick of catching her attention by selling fine fabric (Janezic, p. 266). The Golden Mermaid has some siren-like attributes, singing and trying to beckon the prince into the water, but fits a lot of feminine stereotypes such as being easily lured with pretty fabric. Still, bear in mind that she's stronger than she might seem to modern readers. In many versions of ATU 550, the heroines are easily carried off by the evil brothers. They continue to weep and can't be comforted, resisting in their own way, but they are as easily stolen as the horse and bird. The golden mermaid is unusual in that she manages to stay with the dead prince and watch over his body. We don't hear how exactly she pulls this off, but she withstands two murderers to do so, something that shouldn't be written off. You may have noticed that in all this, I haven't explained where the story is from. The story appeared in Andrew Lang’s The Green Fairy Book (1892), its most famous and widespread appearance. The Coloured Fairy Book series was published under Andrew Lang's name, but the real minds at work were his wife Nora and a team of mostly female writers and translators. In The Lilac Fairy Book, one of the last few in the long series, Andrew wrote in a preface: "The fairy books have been almost wholly the work of Mrs. Lang, who has translated and adapted them from the French, German, Portuguese, Italian, Spanish, Catalan, and other languages." The problem is that, as sprawling and influential as these books are, the citations are frequently awful. Many sources are cut short or just plain missing. Remember “Hans the Mermaid’s Son,” simply noted as “From the Danish.” And “Prunella,” due to the title change and lack of any source, is cut off from its Italian roots. I had to go hunting to find these stories elsewhere. For “The Golden Mermaid,” there is a single terse editor's note: "Grimm." But "The Golden Mermaid" isn't in the Grimms' collections. This may be one of the worst errors ever in the Colored Fairy Books. It looks like the editor mixed up “The Golden Mermaid” with the Grimms’ “The Golden Bird,” a different version of ATU 550. In “The Golden Bird,” the hero is not a prince but a gardener's son, although he does win the kingdom by the end. He’s a little feistier than The Golden Mermaid’s weepy prince, although still hapless (instead of getting caught through clumsiness or happenstance, he’s tripped up by greed or by being too sympathetic to his enemies). The love interest is not a golden mermaid, but the princess of a golden castle, and the wolf-wizard’s role is filled by a talking fox who is secretly the princess’s long-lost brother under a curse. Some scholars don't catch this and refer to the Grimms' Golden Mermaid anyway. The Penguin Book of Mermaids, published in 2019, notes the misleading source with some consternation and even suggests that Lang wrote “The Golden Mermaid" as a very loose adaptation of "The Golden Bird," placing the story with other literary fairy tales. But “The Golden Mermaid” is actually a folktale. I was lucky to stumble across the real source through a tiny note buried in Wikipedia. It's from Wallachia, a historical region of Romania, and was first published in Walachische Maehrchen (1845) by the German brothers Arthur and Albert Schott with the title "das goldene meermädchen" (p. 253). In Romanian, the title translates to “Fata-de-aur-a-mării"; I'm not sure whether this is a back-formation by later scholars, or if the story has been collected in the original language. Arthur collected these stories during a six-year residency in Banat, and considered “The Golden Mermaid” not only the most beautiful story in the collection, but superior to the German “The Golden Bird.” It’s funny reading both of these stories together, because they occasionally seem to fill in gaps of logic for each other, or you can see spots where a story started to stray from the standard plotline. “The Golden Bird” has a few odd fragments, like a random fourth quest tacked on (moving a mountain in order to win the princess). Overall, "The Golden Mermaid" has some interesting themes and characters to unpack, and I especially enjoyed seeing a mermaid in a tale type where they don't often appear. References

Further reading: other fairytales left without sources by Lang Text copyright © Writing in Margins, All Rights Reserved

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed