|

The good and wicked fairies in Sleeping Beauty have an interesting heritage. In medieval legend, fairies and fays often attended the birth of heroes to prophesy their fates. These stories go back even further, to mythology and ancient religions, where goddesses looked upon newborn children and laid out their fates.

Perceforest is a French prose romance first printed in 1528, but may have been composed as early as 1330. It's very very long, but there's one section in particular that is clearly a version of Sleeping Beauty. This interlude tells of Troylus and Zellandine, ancestors of Sir Lancelot (yes, that one). When Zellandine was born, her aunt was given the task of setting a table with food for the goddesses who witnessed the childbirth, so that they would be pleased and lay out a blessed life for the child. These three goddesses were Venus, Lucina, and Themis. In myth, Venus is the goddess of love, Lucina of childbirth, and Themis of order. Themis is also the mother of the three Fates, and in this tale she is identified as the goddess of destiny. When the goddesses sat down to eat, Themis' knife was missing. It had just fallen under the table, but Themis felt insulted; thus, she cursed Zellandine to prick her finger with flax while spinning and fall into an unending sleep. The goddess Venus, more kindly disposed to the child, found a way around the curse. When Zellandine falls into a sleep from which she cannot be wakened, the goddess Venus arranges for her paramour, Troylus, to be carried into her tower. Influenced by Venus, Troylus has sex with Zellandine and she becomes pregnant and gives birth while still unconscious. Her newborn son Benuic, trying to suckle, sucks on her finger and draws out the splinter of flax, awakening her. In "Sun, Moon and Talia" - included in the Italian Pentamerone (1634) - the story is much the same, except that there are no goddesses in attendance. Instead, wise men and astrologers cast the newborn Talia's horoscope and foretell that a splinter of flax will endanger her. The story proceeds in much the same way, with a few exceptions. Instead of one baby, the sleeping Talia gives birth to twins named Sun and Moon. And the story does not end with her awakening. The king who found her already has a wife! In her jealousy, she attempts to have Talia and the kids cooked and eaten. Sympathetic servants save them, the queen is put to death, and Talia lives a long and happy life with her family. Unlike Zellandine, Talia displays no trauma after what is, honestly, a rape. Zellandine loves her betrothed but still feels violated, and the narrative at least hints that Troylus' actions are wrong. Talia and the king, though, are hunky-dory. In 1697, Charles Perrault retold this tale as "The Sleeping Beauty in the Wood." The three goddesses of Perceforest are echoed by seven fairies who show up to give gifts at the christening, and an eighth, elderly fairy who shows up unexpectedly. Everyone thought she was dead, so unfortunately they did not provide her a place setting with jewel-encrusted golden utensils like the other seven fairies. When the other fairies give gifts of beauty and good temper, she adds an early death. Like Venus, another fairy softens the curse to a sleep (this time around, it is specifically for one hundred years) and lays the path to an eventual happy ending and romance. The unsavory elements of "Talia" are softened. Perrault's prince doesn't even kiss Beauty. He just happens upon her at the very moment when she naturally awakens. Their children Dawn and Day are born legitimately after a proper wedding and consensual sex. Even the jealous first wife from "Talia" is replaced by a monstrous mother-in-law. These three stories are all different, but all point to legends about Fate and Destiny. In fact, the word "fairy" may ultimately derive from the Latin Fata, or fate. You have the the Greek Fates or Mourai, the Norse Norns, and others worldwide. In the Greek myth of Meleager, the Fates appear a week after his birth to foretell his fate that he will die as soon as a certain piece of wood on the fire is consumed. His mother seizes the wood and puts it in a safe place, but of course eventually the wood is burnt and Meleager perishes with it. These Fates were portrayed as three old women spinning thread; each thread was a human life. Klotho spun the thread, Lakhesis measured it out, and Atropos cut it. There is another medieval work, from before Perceforest, which features a scene similar to Sleeping Beauty. There is no enchanted sleep, but there is the encounter with otherworldly women who have strong feelings on table settings. Le Jeu de la Feuillée by Adam de la Halle is a French play which has been dated from around 1262 to 1278. In one scene, the characters set a table for the fairies: three beautiful ladies named Morgue, Arsile and Maglore, attended by Fortune. Morgue and Arsile crow over the lovely table and the beautiful knives they've been given to eat with, but Maglore doesn't get a knife and is not happy. Morgue and Arsile go on to bestow gifts of good fortune on the men who set the table; for instance, giving one of them fame as a poet. The angry Maglore, however, gives bad fortune (such as baldness). Morgue is Morgan le Fay. She was often portrayed as part of a group with attendants, sisters or companion queens. In her oldest known appearance, she was the leader of nine sisters. She played the "fay attending on the birth" role in stories of Ogier the Dane and Garin de Montglane. In many tales, her group is a multiple of three; the Norse and Greek Fates are three in number. Three is significant. Birth, life and death. Childhood, adulthood, and old age. Europe has widespread traditions of leaving out meals for a goddess-fairy and her retinue on certain nights (often around midwinter). If the house is in order and the food has been left out properly, the goddess will be pleased and bless the house - but when angered, some versions turn violent. In many cases, this goddess oversees tasks of spinning. She may have names like Spillaholle (Spindle Holle), Spillagritte, Spellalutsche,or Spinnsteubenfrau. Again we have a goddess tied to spinning, just like the Fates. One other similar medieval tale: in the 13th-century French work Huon of Bordeaux, the hero meets Oberon, a diminutive sorcerer. Oberon 's birth was attended by noble and royal fairies, but one grew angry because she "was not sent for as well as the others." As a result, she cursed him never to grow taller than a three-year-old. Intriguingly, the 14th-century Turin manuscript identifies Oberon's mother as none other than Morgan le Fay. The Sleeping Beauty we know today has strong similarities to both "Talia" and Perceforest. The incident of the missing knife travels from "Le Jeu de la Feuillee" (13th century) to Perceforest (16th century) to Perrault (late 17th century) where each fairy receives "a solid gold casket containing a spoon, fork, and knife of fine gold, set with diamonds and rubies." "Sun, Moon and Talia" does not fit into the pattern as neatly. Despite the supernatural qualities of Talia's sleep, it's apparently random. Zellandine and Sleeping Beauty are victims of Fate personified, a being which can be angered or appeased by human actions. But for Talia, it's just something that is going to happen, not for any observable reason. Her future is not bestowed by a fairy, but detected by learned men who study her horoscope. Similarly, there are two ninth-century Chinese Sleeping Beauty stories, "Shen Yuanzhi" and "Zhang Yunrong," where it is also simply the heroine's destiny to die young/fall into a coma. However, even in the story of Talia, where there is no angry goddess of fate, her doom is still tied to the act of spinning. She enters her deathlike sleep when she encounters an old woman spinning thread. As Perrault's Beauty pricks her hand on a spindle, Talia gets a splinter of flax under her fingernail. Also, when she gives birth, she is attended by two fairies (fate in Italian) who care for the newborns and arrange food and drink for her. Just like other fays and goddesses, they show up for a birth. "Talia" and the Chinese tales, some of the oldest surviving Sleeping Beauty stories, leave the listener with questions. I'm not sure whether a culture believing in gods of fate filled in those questions, or whether those questions are remnants from a culture that believed in gods of fate. But put all these stories together and it makes sense: Sleeping Beauty's terrible fate was the work of an angry goddess, later reinterpreted as a fairy. Why was this goddess angry? Because the ritual welcoming her to the child's birth, the ritual meant to ensure the child's good health and future, had not been properly performed. So the thread spun by the Greek Fates became a weapon against the child whose life it represented. Another goddess of fate, who had been properly appeased, intervened to help. The moral: honor the gods to ensure your child's good future. 1/4/2020: Editing to add that Burchard of Worms, who died in 1024, reprimanded those who at certain times of year would lay out meat, drink, and table settings with knives for "three sisters" whom he compared directly to the Parcae - the Roman Fates. Women doing this ritual apparently hoped to gain the sisters' favor and aid in the future. Burchard also frowned on people believing that the Parcae meted out newborn babies' fates and gave some men the ability to turn into werewolves. Further Reading

0 Comments

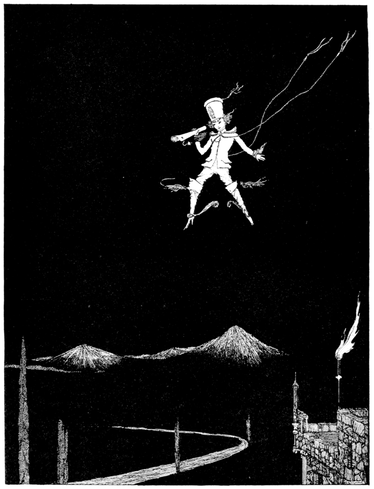

Charles Perrault's fairytale "Le Petit Poucet" - literally "The Little Thumb," my preferred name for it being "Hop o' my Thumb" - has a lot to unpack. In one of the most memorable scenes, Hop o' my Thumb flees with his brothers while the ogre pursues them in seven-league boots. However, the ogre tires and falls asleep, and Hop steals the boots for himself. He goes on to use them as a royal messenger.

Seven-league boots (or as Perrault called them, "bottes de sept lieues," will allow the wearer to walk seven leagues in one step. A league was roughly the distance that a person could walk in one hour, so about three miles. Seven-league boots would thus carry you twenty-one miles at every stride. Seven is a number rich in symbolism and particularly recurrent in "Hop o' my Thumb." Hop is one of seven brothers. The ogre has seven daughters. This was not the first appearance of seven-league boots in Perrault's fairytales. In his version of Sleeping Beauty, there is a brief appearance by "a little dwarf who had a pair of seven-league boots, which are boots that enable one to cover seven leagues at a single step." This is where we actually learn what the boots do - "Le Petit Poucet" leaves the definition out. The dwarf in Sleeping Beauty even serves as a messenger, exactly the same vocation as Hop o' my Thumb. He is a bit character and most adaptations do not include him. Is this a cameo by Hop? Do Perrault's tales share a universe? And what drew Perrault more than once to this specific image, of the incredibly small man in the magic boots? The idea of magical footwear that enables people to travel incredible distances is a universal one, but it seems Perrault made up this particular variation. It spread quickly. In Finnish, they are "seitsemän peninkulman saappaat." In Russian, сапоги-скороходы (sapogi-skorokhody, or fast-walker boots). In German, they are siebenmeilenstiefel. In the Hungarian tale of "Zsuzska and the Devil" - basically a genderflip of Hop o' my Thumb - the heroine steals tengerlépő cipődet, or sea-striding shoes. "The Bee and the Orange Tree" by Madame d'Aulnoy and "Okerlo" by the Grimms feature seven-league boots and a chase scene. The Grimms' "Sweetheart Roland" includes meilenstiefel, literally "mile-boots." An African-American version of the story is "John and the Devil's Daughter," by Virginia Hamilton in The People Could Fly. The idea goes far back in history and mythology. In Greek mythology, of course, there are the Talaria, the winged sandals which allow the god Hermes to fly. In Chinese myth, there are the Ǒusībùyúnlǚ (Cloud-stepping Shoes), which allow the wearer to walk on the clouds. In the Irish tale of King Fergus, the luchorpain gives Fergus shoes that let him safely walk underwater or on water. In Teutonic Mythology, Jacob Grimm mentioned "gefeite schuhe" or "fairy shoes," "with which one could travel faster on the ground, and perhaps through the air." He directly compares these to Hermes' winged sandals and to the seven-league boots. In some versions, the magical traveling shoes are part of a set. In the 1621 version of Tom Thumb, Tom receives multiple gifts from his fairy godmother: a cap that bestows knowledge, a ring of invisibility, a girdle that enables shapeshifting, and finally “a payre of shooes, (that being on his feete) would in a moment carry him to any part of the earth, and to be any time where hee pleased.” In a brief scene, Tom dons the shoes and is "carried as quicke as thought" across the world to view anthropophages, cyclopes, and other monsters. "Jack the Giant-Killer" (1711) borrowed these elements, with Jack winning from a giant a coat of invisibility, a cap of knowledge, a fine sword, and "shoes of swiftness." This is similar to "The King of the Golden Mountain" (Grimm), where the hero tricks three giants into giving him a magic sword, a cloak of invisibility, and "a pair of boots which could transport the wearer to any place he wished in a moment." A similar tale is the Norwegian "Soria Moria Castle" (Asbjørnsen and Moe) with boots that make strides of twenty miles. In "The Iron Shoes," a Bavarian tale collected by Franz Xaver von Schonwerth, the hero's boots let him travel a hundred miles per step and run alongside the wind. There are a multitude of other examples. These objects are all common in legend and might originate in Greek mythology: the sandals of Hermes, the helm of Hades which grants invisibility, and the many transformations of Proteus. A mantle of invisibility belonging to King Arthur is mentioned in Culhwch and Olwen (c. 1100) and other Welsh myths. The tarnkappe - a similar object - plays a role in the Middle High German epic of the Nibelungenlied (c. 1200). Shapeshifting with or without the help of a magic object is a widespread trope throughout world mythology. The hero typically receives these magical tools from a supernatural force: he receives them from the gods or a fairy, or steals them from a monster. The ancestor of them all is the Greek hero Perseus. He is entrusted by the gods with the helm of invisibility and winged sandals, which he uses to slay Medusa the Gorgo. Hop o’ my Thumb bears absolutely no resemblance to the popular modern version of Tom Thumb - which is why it drives me nuts when people mix up the titles! However, there are a few similarities to the 1621 prose Tom Thumb.

Could Perrault have been inspired by Tom Thumb? Is that why he included an unusually small character wearing magic running shoes in two separate stories? Or did he take inspiration from the many other tales of magical shoes? In this case, I think it's very possible he was inspired by the 1621 Tom Thumb. The beginning of Hop o' my Thumb always struck me as a bit out of place; his nickname and implied supernatural state of birth are irrelevant to the story. It's almost as if they were imported from another tale . . . a tale closer to Tom Thumb. On a final note that interested me: unlike Perseus, Hop o’ my Thumb, and Jack the Giant-Killer, Tom Thumb does not use his magical tools to fight any monsters (although he has two run-ins with murderous giants). However, when traveling with his magic shoes, he does see monsters: "men without heads, their faces on their breasts, some with one legge, some with one eye in the forehead, some of one shape, some of another." Their presence serves to indicate just how far he has traveled. Monopods or sciapods are legendary people with only one leg. Blemmyae or akephaloi are headless men with their faces on their chests. Cyclopes or Arimaspi are beings with only one eye. They appeared in the work of Greek writers like Herodotus and Pliny the Elder. Their legends showed up in bestiaries and maps throughout the Middle Ages. Pliny the Elder placed cyclopes in Italy, blemmyae in North Africa, and monopods in India. Some bestiaries put the one-eyed "Arimaspians" in Scythia, in eastern Europe. So magical boots of travel are a very widespread and old idea, usually used in combination with other magical tools, but occasionally appearing on their own. They may have been Perrault's own creative touch. In tales similar to Hop o' my Thumb, there is frequently a chase where the hero must escape the villain, and does so by various means. Hansel and Gretel ride away on a duck. Other characters, like those in Sweetheart Roland, disguise themselves in a transformation chase. Perrault gave his hero magic boots for this scene, and codified them not just as magic boots but as seven-league boots (repeating the use of the number seven). Their presence, along with Petit Poucet's name, is fascinatingly reminiscent of the 1621 English Tom Thumb. What makes it even more interesting to me is that Perrault also used that Tom Thumb-esque character in Perrault's Sleeping Beauty. |

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed