|

In which abstinence is effective 99% of the time, but to be completely safe, you should never eat anything. Or breathe.

I'm gaining a new appreciation for fairytale collections that include notes on the stories. Without it, it can be near-impossible to track down more information on the fairytales. This is what I went through with the Vietnamese Thumbelina, Nang Ut ("Miss Little Finger") for a while. When I found a Vietnamese version, there was one thing that really surprised me . Namely, Nang Ut is a mother. A prince visits her garden, eats one of her melons, and throws the rind away. After she eats from the rind as well, she becomes pregnant. The prince eventually returns to her and decides to stay with her and their son. This kicks off the Doll-in-the-Grass plot of bride tests. Nang Ut's birth is unusual, and so is the birth of her son. However, she is a "petit monstre," while her son is a miraculous child. Nang Ut's parents pray for her birth and undergo an unusually long pregnancy which results in an incredibly tiny daughter. This is in contrast to the German Thumbling, who is born after an unusually short pregnancy. Thumbling's story suggests premature birth, but Nang Ut is more reminiscent of a stone baby, who dies but remains inside the mother's body. While Thumbling's parents are loving, Nang Ut's parents abandon her because of her small size and monstrous nature. Her son's size is unclear, or not remarked on. She's able to care for him, and in Landes' version she can hold him in her arms. In a visual adaptation on YouTube, however, the boy is of average size. Unlike Nang Ut's parents, the prince accepts her. Their child unites them instantly. Food and drink as the cause of supernatural pregnancy is an incredibly widespread motif. A woman is told to eat some flower or herb, and the resulting child is often extraordinary in some way. (We see this again and again in thumbling tales. Three-Inch's mother eats a cucumber; Bitaram's mother steals a fruit; Pinoncito's mother is given a piñon nut.) Edwin Sidney Hartland has a huge list of variants, jumping off from the tale of Perseus, where Zeus takes the form of a golden rain to visit Danae. A more specific variant, which might lend a little more internal logic to "eating from the same melon causes pregnancy," is that the food has been contaminated by a man's... um... bodily fluids, whether that's tears, saliva or something else. In the earliest printed version I could find (a French translation by A. Landes in 1886), a footnote explains the implication that the prince made water into the watermelon's rind before throwing it away. Hartland mentions a similar tale, "The Lazy Man," also from Vietnam. Some modern versions, like the folk opera on YouTube, cut out the pregnancy entirely and simply have the two meet in the watermelon garden. In a clever variation, Vuong has the rind accidentally strike Nang Ut when it's tossed away, so that the two meet immediately. On another note, Nang Ut is an example of the Animal Bride tale, type 402 - very similar to Doll i' the Grass and Terra-Camina. I've commented on this before, but these characters are all associated with nature. Doll-i'-the-Grass with, um, grass, and Terra-Camina with earth. Nang Ut continues the pattern. She's a gardener. Her identity is tied to this place where she lives, surrounded by vegetation, so that her story shows up under titles like "Little Finger of the Watermelon Patch" or "Thumbelina in the Bamboo Tube" (Nàng Út Ống Tre). Although in these variations the bride is not an enchanted animal, she is still a being connected to nature. SOURCES

0 Comments

Oberon's Lineage In the 13th-century Huon of Bordeaux, Auberon is the son of Julius Caesar (!) and Morgan le Fay (!!). In the following century, there was a prequel, Roman d' Auberon (Romance of Auberon) more backstory is given. Here we learn that Auberon's great-grandfather was Judas Maccabeus, and his twin brother is St. George the Dragon Slayer. Some of these ideas stick around. Ogier le Danois has Oberon as Morgan’s brother. In the play "Fairy Pastoral, or Forest of Elves," by William Percy (1603), Oberon's father and the previous king of the Fairies was named Julius, although the author apparently also considered the name Olbion. In The Faerie Queen, Oberon is the son of Elficleos. (In this cosmology, Elficleos stands for Henry VII, Elferon is Prince Arthur, and Oberon is Henry VIII. And there are way more Elf names. It's a little annoying.) In "Oberon, the Faery Prince," a masque by Ben Jonson (1616), Oberon (representing/played by Prince Henry Frederick) is the heir to King Arthur (James I). This is an interesting reversal of stories such as the thirteenth-century Huon of Bordeaux, where Arthur is a prospective heir of Oberon, though the fairy king ultimately chooses Huon as his successor. This seems like a good point to tie in to other heirs of Oberon. Children of Oberon In Spenser's The Faerie Queen (1590), Oberon's daughter Tanaquill rules after him and takes the royal name Gloriana. King Arthur is wooing her. In the children's play "The Court of Oberon, Or The Three Wishes: A Drama in Three Acts," (1831) by Elizabeth Yorke, Gloriana is the princess and daughter of Oberon and Mab. In The mad pranks and merry jests of Robin Goodfellow (1628), Robin Goodfellow is the son of Oberon and a mortal woman. In the poem Kensington Gardens, by Thomas Tickell (1722), Oberon's daughter is named Kenna. She tragically falls in love with a human changeling and lends her name to Kensington Gardens. There was also a comic opera that was a sort of fan sequel to this, A Princess of Kensington (1903). In the masque The Fairy Favour, by by Thomas Hull (1767), Oriel is the fairy prince and heir of Oberon and Titania. Oberon is descended from the character Alberich. Ortnit was a German heroes who replaced the mythical Hartnit, one of the Hartung brothers. These heroes were the sons of the Russian hero Ilya Muromets. Hardheri became Wolfdietrich, and more appropriate to this post, Ilya was replaced by Alberich. Walbert (or Wambert) was eldest son of Alberich the magician in the legendary history of the Merovingian dynasty. (Alberic/Aubert/Auberon is brother to Merowech/Merovee and husband to Lucilla, the daughter or sister of Emperor Zeno. His father was Clodion. In this lineup, Pepin and Charlemagne are Alberic's descendants.) In the Wagner Dramas, Alberich is the chief of the dwarves and villainous Nibelung who steals the Rhine maidens’ gold, and is the father to Hagen, who murders Siegfried. Hagen’s mother is a human woman named Grimhilde and his half-siblings are Gunther and Gudrun. Here, Auberon's brother is the smith Mime. There are plenty of modern books featuring children of Oberon and/or Titania; however, the latest one that really fascinates me is Titania's Palace, also known as possibly one of the cutest things I've ever seen. TITANIA'S PALACE

THIS IS THE MOST AMAZING DOLLHOUSE. The creator was Sir Nevile Wilkinson. The story is that the project was inspired in 1907, when his three-year-old daughter Guendolene said she'd seen a fairy at a nearby tree. This inspired a massive project of an elaborate dollhouse known as Titania's Palace, which took years to complete; it included numerous pieces of artwork, including tiny books with actual writing, and the display opened to the public in 1922. Wilkinson wrote storybooks for his daughters which mentioned Titania and her prince consort, Oberon; in this private mythology they had seven children. The four girls were Iris (the oldest), Ruby, Daphne and Pearl, and the boys were Zephyr, Noel, and baby Crystal. For these children there were bedrooms and miniature clothes and toys throughout the palace, and even a tiny perambulator. EDIT: Wilkinson's book Yvette in Venice gives more details on the children. The four daughter all have elemental powers. Iris (12) is chief of the fairies of the air and whe wears a rainbow around her head. Zephyr (11) has no information given. Ruby (9) has the element of fire. Rules over the elves and gnomes who mine precious ores. She has brown hair and hazel eyes. Daphne (7) is the most social of the princesses and cares for the wood and garden fairies. Noel (5) is said to help Father Christmas distribute presents. Pearl (3) is a great swimmer, so presumably affiliated with water fairies. Crystal (7 months) is said to be a very cheerful baby. They also have a car, the Grey Fairy, and a Pekingese named Prince Ching. SOURCES

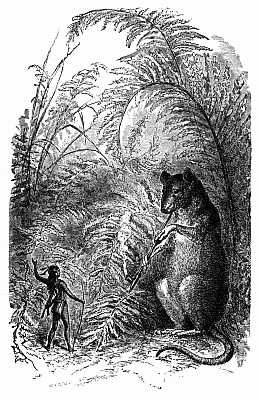

Several lists of Thumbling variants include Boy-Man. However, when I first started looking it up, I didn't have much to go on. (I didn't even know what nation it came from.) The only thing it really had in common with the other Thumblings was that the hero got swallowed by a fish. Boy-Man was small, but baby-sized, not thumb-sized - a feature that made the story slightly less fantastical and miniaturized. But as I researched, I realized that it was part of a widespread narrative. Just not necessarily the Thumbling narrative. It's its own story! About a little baby-sized man who fights giants and is associated with the solar system! This family of stories is all Anishinaabe. Anishinaabe is an Algonquian nation in the Lake Superior region. They are also known as Ojibway or Chippewa, and are related to the Ottawa and Potawatomi. I listed these stories on the Thumbling Encyclopedia as I found them, but I think they deserve an article of their own. Boy-Man (Ojibwa) Girl and boy alone: A little boy and his sister live alone on the shore of a lake. Dwarf hero: Boy-Man remains infant-sized, but is brave and strong. The Frozen Lake/Battle with a Giant: His sister warns him to be careful on the frozen lake, but makes him a ball. He runs out onto the lake, bouncing his ball, and finds four identical giants spearing fish. He grabs a fish and runs away. The next day, he drops his ball into the ice hole and asks the men to retrieve it. Instead they make fun of him and push it under the ice. In response, Boy-Man shoves them all in and retrieves his ball. (In Pa-ha-sa-pah, he’s strong enough to break one guy’s arm.) After he’s gone, the men get out, but decide to hunt him down. Their mother warns them not to, since he’s a manito with powers. They go off anyway. His sister sees them coming and is terrified, but Boy-Man just eats his lunch. When he turns his dish over, the doorway is blocked by a stone. The men make a hole in the stone, but he shoots each one of them as they look through. In Schoolcraft’s version and in Pa-ha-sa-pah he cuts them smaller, so that men will never be giants again, only their present size. In Wade’s version, he sends the men (who may or may not be dead) perpetually wandering in the four directions, north, south, east and west. Bow from sister. In spring, he has his sister make him a bow and arrows (Pa-ha-sa-pah) and goes out into the lake (against her advice). Swallowed by a Fish: He calls a huge trout to swallow him. It does so, and he calls out to his sister to fetch him a moccasin. She throws it out tied to a string, and manages to reel the fish in after Boy-Man instructs it to eat the moccasin. His sister cuts him out. Commentary: This tale is also called "The Little Spirit" or "The Little Monedo." Wade adds a section where Boy-Man lights the house with fireflies at his sister’s request. Pa-ha-sa-pah places the story at Spearfish Creek in the Black Hills. It mentions that his people have never seen a dwarf before and look down on him. Some call him a “puk-wud-jinine, or fair[y] of the hills,” but he is human. However, Boy-Man has power and unusual strength because the gods took pity on him and blessed him. There's an unrelated character named Boy-Man in Sioux legend. Wa-Dais-Ais-Imid, or He of the Little Shell (Ojibwa) Girl and boy alone: Sister and younger brother are only survivors of an unknown disaster. Dwarf hero: grows very slowly. “He had now arrived at the years of manhood, but he still remained a perfect infant in size.” Depending on version, he’s known as Wa-Dais-Ais-Imid or the shorter version, Dais-Imid. This is because his sister gives him a magic shell to wear around his neck. Interestingly, Dais-Imid has the power to become invisible, and when visible wears a kind of halo. Bow from sister. He begins with shooting tom-tits and squirrels, and slowly becomes a great hunter. The Frozen Lake/Battle with a Giant: While hunting, he approaches a frozen lake and finds a giant killing beavers. Dais-Imid cuts the tail off one of the beavers (the author justifies this because the beaver dam belongs to “the little shell-man and his sister.” This happens a second and third time; however, the giant can’t catch Dais-Imid, because he has the power to become invisible. The angry giant, revealed to be Manabozho, tries to fight him, but Dais-Imid makes a fool of him by pretending to hide inside the giant’s nostril or in other places. Manabozho’s appearance here as a dull-witted giant is odd. In other places, Manabozho or Nanabozho is a benevolent shapeshifting Anishinaabe/Ojibwa hero. Dais-Imid takes Manabozho’s usual place as the trickster. Heavenly Bodies: Upon returning home, Dais-Imid tells his sister that they must separate. She will become the Morning Star, and he will live in the mountains and be called ‘Puck-Ininee, or the Little Wild Man of the Mountains.’ This is a clear relation to the pukwudgies or pukwujininees of Ojibwe/Algonquin lore, but the spelling here is reminiscent of the English Puck. Dais-Imid explores briefly to meet other manitos. One giant throws him into a kettle to boil him, but he bails out the water and escapes. Returning to his sister, he tells her that there is a manito “at each of the four corners of the earth.” There is also a Great Being in the sky, and a wicked one deep down in the earth. (A very Christian cosmology.) The siblings are apparently separating to escape this evil being; I don’t know why. It’s unclear whether the evil being is the same as the giant who tried to boil Dais-Imid, and was described as a cousin of Manabozho. The four winds will blow his sister to her place in the sky. Dais-Imid runs up a mountain with his ball-stick, singing a song to the winds Little Brother Snares the Sun (Anishinaabe). Retold by Richard L. Dieterle. Girl and boy alone: In the beginning, men are weak and are hunted to near-extinction by the animals. The only survivors are a girl and her younger brother. Dwarf hero: The sister has to take care of her brother, who is still no bigger than a newborn. Bow from sister. She gives him her bow and arrows and tells him to shoot a snowbird. He misses three times before getting a hit, and finally shoots ten snowbirds. The Shrunken Coat: His sister makes a coat for him out of their skins. Little Brother goes out into the wilderness (looking for other humans), but while he sleeps, the sun’s heat shrinks his coat. The Magic Rope: He fasts for twenty days and tells his sister to make a strong rope that can snare the sun. His sister gives him an ordinary rope, which he rejects as not strong enough; then a snare of deer sinew, then a rope of her own braided hair, and then one of “secret things” that Little Brother uses to make a magical rope. He travels to the beginning of the sun’s path and lays his snare. When the sun is trapped, darkness falls over the earth. The Great Mouse/Council of the Animals: The animals hold a council. The dormouse, a huge man-eater, gnaws the sun free but becomes tiny in the process. As a result of all this, humans will now have power over the animals. Commentary: Dieterle suggests special connection between Little Brother and snowbird – Little Brother is creature of the snow, and is diametrically opposed to the sun. This tale has been identified as a Hočąk [Winnebago] myth from Michigan, but is actually Anishinaabe and seems to have first been recorded with Schoolcraft's Myth of Hiawatha. There are multiple instances of this tale recorded.

So Boy-Man, Dais-Imid, and Little Brother Captures the Sun are three tales from the same family, as seen by the common motifs. The dwarf hero lives in isolation with a sister who gives him a bow and arrow for him to go out hunting. Boy-Man and Dais-Imid share an adventure on a frozen lake and a battle with giants whom they trick. Dais-Imid makes a journey to the sky and has a connection with the stars, while Little Brother travels to the beginning of the sun’s path. So is there a story that marries all of these motifs into one narrative? The answer to that question is YES. THERE MOST ABSOLUTELY IS. The Tale of Tshakapesh Oral Innu poetry. Girl and boy alone: A man and woman out collecting birch bark are killed by a monster called Katshituashku. Their unborn child survives, since the creature doesn’t eat the woman’s womb, and their young daughter eventually finds the baby. Dwarf hero: Tshakapesh begins the story as an infant. He is usually depicted as a dwarf or young boy. Bow from sister/Trees for arrows: She makes him a tiny bow, which he breaks, and gradually makes him bigger and stronger bows until he’s using an entire tree. Vengeance for Parents: Against his sister’s advice, he goes to hunt Katshituashku. He kills him and finds in his stomach his father’s hair. If he had found the bones, he could have brought him back to life, but with just the hair, all he can do is make it into tree moss. He takes his sister some bear meat. When she eats it, her jaw locks into place. Tshakapesh pries her mouth open and says that from now on, people’s mouths will be three fingers wide. (How big were they before?!) Swallowed by a fish: He later has a dream that he was swallowed by a trout. When he doesn’t return from hunting, the sister remembers the dream and goes out fishing. Tshakapesh, inside the trout, tells it to take the hook. The sister catches fish after fish and cuts them open, until she finds the one with Tshakapesh inside. The Frozen Lake: He returns to hunting, but his sister warns him about some people who are out on the frozen lake, hunting a giant beaver. They try to get others to grab the beaver as a prank, since anyone who tries will be pulled into the water. Tshakapesh promises to stay away and immediately goes out to find them. When they try to get him to pull the beaver through a hole in the ice, Tshakapesh succeeds—twice. They try to claim his two beavers when he’s about to leave, but stop because it’s Tshakapesh, who succeeds at everything he does. Battle with a Giant: Disobeying his sister once again, Tshakapesh approaches the home of Atshenashkueu, the giant cannibal’s wife, and her two daughters. He puts snowbird feathers in his hair, and the daughters mistake him for a jay at first. They decide to help him, and warn him not to eat the food (human meat) that their mother will offer him at dinner. They want to marry him. The mother challenges Tshakapesh to a wrestling contest, but he makes himself so heavy that she can’t move him. He kills her instead and takes the girls home and marries one of them. Time to disobey his sister again! She tells him to stay away from the mishtapeuat, who are playing ball with a bear’s head. Tshakapesh approaches, spots the most skilled player, and decides to take him home to marry his sister. So of course he does. While hunting with his new brother-in-law, he has another sister-banned adventure where he gets boiled in a cauldron but survives. When he climbs out, he strips off his protective covering and also all the hair on his body, announcing that from now on people will only have hair on the top of their heads. Tree grows to sky/The Magic Rope/Council of the Animals: He climbs a white spruce by blowing on it to make it taller, and winds up in a place where he lays a snare. The Sun is accidentally trapped in this snare. Tshakapesh tries to disarm the trap by throwing a squirrel at it, but it burns up. A mouse also burns up, but a water shrew succeeds. Heavenly Bodies: He decides to bring his whole family to live in this sky place. They all climb up the tree before he blows on it and returns it to its normal size. They all live on stars; Tshakapesh lives on the moon and his sister on the Morning Star. From this one (long) narrative, you can pick out all three stories - Boy-Man, Dais-Imid, and Little Brother! Tshakapesh is a figure similar to Manabozho, which makes it even more interesting that Dais-Imid fights Manabozho. There are elements of a just-so story – the size of human mouths, humans being hairless. (So before Tshakapesh, people were covered in hair and had larger mouths . . . read, more animal-like.) I found more short stories that are really episodes from the long version. When Tcikabis trapped the Sun (Atikamekw) has a Tree Grows to Sky; a variant of The Shrunken Coat where Tcikabis falls asleep in the sky and the Sun burns him; The Magic Rope via a magic net; and a Council of the Animals, where the turtle, rabbit and squirrel are too big to get close, but the mouse succeeds. Tshakapesh and the Elephant Monster (Innu) tells the origin story where an elephant kills his parents, his sister makes him a bow and arrow (graduating from little ones to whole trees), and he avenges his parents but decides not to bring them back to life. Chakabech is a Wyandot version recorded by Paul le Jeune. Chakabech's parents are killed by a bear and by the Great Hare, but a woman adopts him as her little brother and gives him his name. He's a Dwarf Hero no bigger than a baby but uses trees for arrows. After avenging his parents, he blows on a tree until it reaches the sky, and then climbs it into a beautiful country. He takes his sister to live up there (Heavenly Bodies). When he’s hunting, his snares manage to catch the sun (The Magic Net). The story wraps up with The Great Mouse/Council of the Animals: He finds a little mouse and blows on it until it becomes big enough to free the sun. In the Dogrib story of Chapewee, the hero seems to be a Noah-esque figure recreating the Earth. He creates a fir-tree so tall it reaches the sky, goes hunting in the sky with a snare made from his sister’s hair, and the sun gets trapped. Chapewee sends up animals to free the sun, but they are all burnt to ashes. A ground mole succeeds by burrowing underground, but it loses its eyes in the process. The hero is the typical trickster figure. The giant tree reaching to another realm is a motif shared with Jack and the Beanstalk. Dais-Imid and Little Brother don't feature the tree, per se, but do have similar journeys to the land of the sky. The tale of the animal rescuing the sun is also widespread across the world. It even feels similar to the myth of Prometheus. It’s interesting that in this one, it’s the hero who’s holding the sun captive. However, it's not unheard of. Sometimes the culprit is a culture hero, like the Winnebago character Hare. Maybe theres a correlation between the small size of these animals and the small size of the dwarf hero. In a tale from the Bungee Indians from Lake Winnipeg, it's the god Weese-ke-jak (Wisakedjak) who catches the sun in an enormous trap to light the earth. The sun’s heat threatens to burn everything, so they compromise. The beaver chews the trap open and is rewarded with its current appearance. Some stories have the element of eternal night, and others don't. I'm looking up Aarne-Thompson motifs to find other parallels, but that can be slow going. SOURCES

In many stories, brownies are helpful little sprites who are eager to work and clean for human families. However, if clothes are left out, the brownie vanishes, never to be heard from again. And they'll usually announce this in rhyme. But why? The explanation varies by story. Some brownies are thrilled to find their new clothes. In fact, it seems to go to their head a little. In the German story of The Elves and the Shoemaker, the elves sing, "Now we are boys so fine to see, Why should we longer cobblers be?" In a similar tale, the household fairy's cry is, "Pixie fine, Pixie gay, Pixie now will run away." More often, though, it is simply a taboo and even the best way to drive off an unwanted brownie. "Here’s a cloak and here’s a hood! The Cauld Lad of Hilton will do no more good!" Another rhyme goes, “Gie Brownie coat, gie Brownie sark, Ye'se get nae mair o' Brownie's wark!” In some variations they'll leave if you pay them anything – food counts too. Keightley's Fairy Mythology explains that Brownies do their work out of generosity and are greatly turned off by anything that would look like payment or a bribe. (And in some places, like Berwickshire, England, it's less voluntary and they simply cannot take payment, being appointed by God to be the pro bono "servants of mankind".) However, they’ll accept gifts that are given discreetly. Clothes or fancy food are too much, but a simple bowl of cream and honeycomb left quietly somewhere out of the way will be gladly accepted. He gives an example of a woman making an outfit for her brownie and making the mistake of calling out to let him know it’s there. This prompts him to say, “A new mantle and a new hood; Poor Brownie! ye'll ne'er do mair gude!” Often the implication is that the brownie is deeply insulted by the gift - as with Puck, who would "chafe exceedingly" at the compassion of those who laid out clothes alongside the milk and bread he preferred. "What have we here? Hemton hamten, here will I never more tread nor stampen." Alternately, in The mad Pranks and merry Jests of Robin Goodfellow, a maid makes the mistake of leaving him a waistcoat instead of food. Big problem. Because thou layest me himpen hampen I will neither bolt nor stampen: 'Tis not your garments, new or old, That Robin loves: I feel no cold. Had you left me milk or cream, You should have had a pleasing dream: Because you left no drop or crum, Robin never more will come. (Keightley 288) In "hempen hampen," hemp would be the coarse cloth that the clothes are made from. This may link to another variant, where the brownie is fine with the idea of clothes - it's the shoddy material that offends him. In a Lincolnshire version, the brownie announces, “Had you given me linen gear, I would have served you many a year.” Another explanation is that giving him clothes says you’ve seen him. You would have to wait up late at night and spy on him to know what he's wearing. He's happy with his rags, thank you very much. On the other hand, in a tale from the Scottish Highlands, the brownie welcomed the idea of clothes and would regularly make bargains with the house-servants. The agreement was for him to do the winter’s threshing in exchange for a coat and hood that he liked. However, when they laid out the clothes ahead of time, and he grabbed them and took off, with the words “Brownie has got a cowl and coat, and never more will work a jot" (Keightley). Most of these are either gleeful and self-satisfied, or insulted and angry. However, in one story the brownie sounds quite sad. On the Isle of Man, the story is that a brownielike creature called the Phynnodderee helped in moving some stones. The grateful owner left some clothes for him in the glen where he lived. Upon finding them, the Phynnodderee cried, Cap for the head, alas, poor head! Coat for the back, alas, poor back! Breeches for the breech, alas, poor breech! If these be all thine, thine cannot be the merry glen of Rushen. (Keightley) This has stuck around in popular culture. In the Harry Potter series, house elves can be freed from servitude by a gift of clothing. A summary of reasons why:

SOURCES

Actually, this started out as "Why does Peter Pan have pointed ears?" That was fairly easy. It was Disney’s creative choice to depict him that way. The pointed ears, a trait shared with the fairy Tinker Bell, emphasized the character’s magical and otherworldly nature. The two also wear green – a color traditionally given to fairy clothing. Any other sources showing Peter Pan with pointed ears seem clearly drawn from Disney. So . . . pointy ears are a marker of an otherworldly nature, common to elves and fairies. When did that happen? Here, elves and fairies are basically synonymous, as in Shakespeare. A lot of sources automatically point to Tolkien as the one who popularized the pointy-eared elf; however, Tolkien never described his elves in-depth. In fact, in the fandom, opinions are divided on whether his elves’ ears are really intended to be pointy at all. In some of his letters, he did say that their ears were “leaf-shaped” and that a hobbit’s ears were "ears only slightly pointed and 'elvish'" (Letters, 35 (27), Annotated Hobbit, 10); however, in that second case, it's possible he was referring not to his elves but to the little Santa-style elves of contemporary imagination, who already had pointy ears. Either way, Tolkien was by no means the first or most famous user of pointy-eared elves. So then where does the trend really begin? As far as I can tell, it starts with satyrs. There were many animal-human hybrid monsters in Greek and Roman myth. Silenus, part man and part donkey, was depicted with a donkey's pointed ears. Satyrs had goats' ears and legs. Later, as Christianity rose to power, these kinds of magical creatures were demonized, and pointed ears and hooves became the attributes of the devil. And fairies were also at odds with Christianity. Creatures who could be frightened away with holy symbols or the sound of church bells. I think the most important bridge here is none other than Robin Goodfellow, or Puck. Puck was a fairy being, but often the line between Puck and Devil was blurred. An early woodcut from Robin Goodfellow: His Mad Pranks and Merry Jests (1629) shows Puck as a faun, resembling the gods Pan and Priapus. Looking at Puck's donkey ears here, it’s easy to see how they could develop over the years into Tinker Bell’s ears. (Incidentally, Peter Pan does have similarities with the god Pan. The name, for one. And the panpipes.) See also Peter Paul Rubens's 1616 version of Silenus and the Satyrs here. In 1789, a more innocent and childlike Puck appeared in a painting by Joshua Reynolds. The goat legs are gone, but the pointy ears remain. A Midsummer Night's Dream is the source for a lot of fairy paintings. Joseph Noel Paton painted a few - one, in 1849, was the Quarrel of Oberon and Titania. It's a huge and detailed scene, showing many wildly varied fairies. Some have little butterfly wings. Oberon and Titania appear human in shape, but godlike. Of their smaller subjects, some bear butterfly wings, and I think at least one has pointed ears. This kind of variety in size and appearance is par for the course in this era. Still, in folklore and fairytales, there aren't many mentions of fairy ears. You'll get dwarves with long beards or ladies of extraordinary beauty or trolls with huge noses, but ears are rare. When they do show up, they are not quite the delicate pointed ears of Tinker Bell. In A Peep at the Pixies, or Legends of the West by Anna Eliza Bray [1854], the fairy called Pixy Gathon is described with “very large ears, hairy and long, resembling those of a donkey.” He also has a tail. This is pretty close to Puck and Pan. Back to the Greeks for a moment. The sculpture of the Resting Satyr was attributed to Praxiteles, who lived in the 4th century BC. The nude figure appears entirely human except for its pointed, goat-like ears. Why do I bring this up? Because it might shed some light on why fairies are shown with pointed ears.  In 1860, Nathaniel Hawthorne based his work The Marble Faun on this sculpture and described it thus: "These are the two ears of the Faun, which are leaf shaped, terminating in little peaks, like those of some species of animals. Though not so seen in the marble, they are probably to be considered as clothed in fine, downy fur. . . . The pointed and furry ears . . . are the sole indications of his wild, forest nature." So the inhuman ears are the main clue to the beautiful creature’s true, otherworldly nature. Hawthorne's book seems to have been pretty well-known at the time. Perhaps this lent itself to a growing trend of oddly-eared creations. During the Victorian era, fairies become a popular subject in art. Some fairy artists in the 1800s were John Anster Fitzgerald, Richard Dadd, and Richard Doyle. However, there seem to be classes of fairies. There are the tall, humanoid fairies with flowing hair, like Oberon and Titania. Then there are the Pucks, the tiny, grotesque and pointy-eared gnomes. Pointed ears are an attribute of more wild and inhuman creatures - ranging from comically grotesque to monstrous. Check out Dadd's "The Fairy Feller's Master Stroke." 1882 - Walter Crane's illustration of The Elves and the Shoemaker by the Brothers Grimm. Later editions will also have pointy-eared elves - like the 1911 translation with illustrations by Charles Folkard.  1884: Andrew Lang’s Princess Nobody with illustrations by Richard Doyle. Some of the fairy creatures bear ears that are large and elongated , but not exactly pointy. In English Fairy Tales, by Joseph Jacobs, published in 1890, there are two mentions of pointy-eared fairies. In "Fairy Ointment," some fairies are apparently human-sized and very beautiful, with clothing of "white silk" or "silvery gauze." However, the smaller fairies or pixies are “flat-nosed imps with pointed ears" and "long and hairy paws.” In "The Cauld Lad of Hylton," a brownie is described as “half man, half goblin, with pointed ears and hairy hide.” In both cases, the pointy ears come with a hairy appearance, increasing the similarity to a wild beast.  1899: The first comic strip of The Brownies by Palmer Cox is published. This series, which stars small, pudgy brownies with slightly pointed ears, becomes incredibly popular and even gets a camera named after it. 1901 illustration from Queen Mab's Fairy Realm, a collection of stories edited by George Newnes and illustrated by Arthur Packham. Notice the two different types of fairy shown here. Rackham (1867 – 1939) illustrated tons and tons of fairytale books, and is another huge influence on how fairies are viewed. His fairies vary in the ear department; some pointy, some not so. Many, usually the grotesque ones, have pointed ears. His illustrations for A Midsummer Night's Dream and Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens are of particular note here. In 1902, the Life and Adventures of Santa Claus by L. Frank Baum was published. Mary Cowles Clark drew the illustrations, which included little fairy creatures with antennae and large, elongated ears. (A human-sized nymph with long flowing hair does not have particularly pointy ears.) 1906: Puck of Pook's Hill, by Rudyard Kipling. Puck, or Robin Goodfellow, is of course a central character. Here, he is the size of a small child, and carefully described as "a small, brown, broad-shouldered, pointy-eared person with a snub nose, slanting blue eyes, and a grin that ran right across his freckled face." A Puck costume also includes the ears - so now, in text, we get the idea that this is a defining trait of this character. (Anything in text is particularly interesting, because while the pointy-ears thing is now popping up everywhere in art, it's been hard to find textual evidence.) In a 1909 article from the Manchester Guardian, quoted here, brownies are “little men with big eyes and long ears.”  Florence Harrison was another artist who drew many fairies for fairytale books. In books such as the 1912 Elfin Song, her brownies, elves and banshees had quite large and pointed ears. They look very Rackham-esque.  1912: Swedish magazine Among Gnomes and Trolls #6 - one of many illustrations by John Bauer shows a pair of trolls with long ears. However, a small fairy with long golden hair has her ears hidden.  In 1922, Norman Rockwell drew Santa Claus surrounded by tiny, pointy-eared elves.  Flower Fairies of the Spring (1923) was the first of many books by by Cicely Mary Barker. Her fairies resemble Tinker Bell in that they are small and winged. They frequently have their ears covered by hair or hats. However, when their ears are exposed, as shown here in the Acorn Fairy picture from Flower Fairies of the Autumn, they are definitely small and pointed. Mopsa the Fairy (1869) by Jean Ingelow has fairies of varying sizes who start as tiny infants. There's no textual mention of their ears, which seem to be covered by their hair in the original illustrations. However, in a 1927 edition, Dorothy P. Lathrop's illustrations give the baby fairies large, pointed ears.  1933: A Bunch of Wild Flowers, by Ida Rental Outhwaite, has different varieties of fairies. Notice that again, the smaller, cartooned one has large ears, while the more realistic fairy has her ears covered by her hair. 1935: Goldie the elf in Disney’s “Midas” short has round ears. So pointy ears still aren't ubiquitous. 1937: Tolkien publishes The Hobbit. 1939: In illustrations for Enid Blyton's series The Faraway Tree series, the fairies are clearly point-eared. A brownie character is named Big Ears. 1953: Walt Disney produces Peter Pan and I think from this point you can just solidly say that fairies are going to be little and sparkly with wings and, most importantly, pointy ears. Especially because Tinker Bell quickly becomes a mascot for Disney. (The pointy ears were Disney's initiative even in Tink's case. In the original book Barrie makes no mention of them that I can find, and in the illustrations she is too small to tell what her ears look like.) 1954: Hi again, Tolkien. (By the time he's written the Fellowship of the Ring, he's actually moved farther away from fairies and folklore, and has created his own brand of elf. But that's a whole different subject.) In 1967, on the Star Trek episode "This Side of Paradise," Kirk tells Spock, "You're an overgrown jackrabbit, an elf with a hyperactive thyroid." In 1968, the Keebler Elves were created. And in 1977, in the novel The Sword of Shannara, elves have “strange pointed ears.” By this point, pointy ears have become typical attributes of elves and fairies. So why did this trait become popular? Pointed ears are a quick way of showing that a character is not entirely human. They’re also easy to draw or to create in costumes. Personally, I'd point to Disney's Tinker Bell as well as Rackham's illustrations and Barker's Flower Fairies as the ones who really popularized the modern idea of the fairy. The pointed ears lead back to brownies and hobgoblins like Puck, and through Puck to Greek satyrs. Ultimately, this trait is a way to show that a being is nonhuman - perhaps wild or monstrous like an animal, but always otherworldly. Sources and further reading

Ditu Migniulellu, a tale from Corsica, is utterly unique. I have never seen any other story combine elements of Cinderella with Thumbling like this. However, as I started studying it, I started seeing layers that I had missed entirely on the first read. For one thing, I never realized that it’s a variant of Donkeyskin. Donkeyskin (AT 510B) is similar to Cinderella (AT 510B), but the typical elements go something like this:

Incidentally, the first recorded versions of Donkeyskin appeared in France and Italy – and guess where Corsica is. The story starts out typically for a thumbling tale, with a woman who's sad because she has no children. In the older French version by Ortoli, the woman is promised a child by a voice from the roof. Ruth Manning-Sanders' English translation has a more involved version where the woman encounters a fairy of the stream, who gives her a white berry to eat. One way or another, the woman has a baby who’s no bigger than her finger, and four fairies appear to give christening gifts. They give the baby the name Ditu Migniulellu, or Little Finger. She receives beauty, a beautiful singing voice, and the ability to speak. The first of the fairies promises to come whenever D. M. needs her. When Ditu Migniulellu is sixteen, she’s still the same size and her mother has come to resent and then to hate her. Out in the garden, she traps her beneath a pot and leaves her there. At first D.M. protests, but then she decides to be patient and starts to sing. The prince just happens to be passing by, and is amazed by the beauty of her voice. Rashly, he swears to marry the singer. Ditu shares her beautiful singing voice with characters like Sleeping Beauty, Rapunzel, and Thumbelina. Singing was a valuable talent and good way for entertainment, and a trait deserving of high esteem, says SurLaLune. And it’s her voice which first attracts the prince. However, the scene that follows tells us a lot about where this story is going. She sings to guide him to her hiding place, but he becomes enraged when he can’t find her. He kicks the pot and shatters it. Which probably could have killed her, but she’s okay. Now honor-bound to marry her, he carries her home in his pocket. She calls out that she’s suffocating and so he carries her the rest of the way in his hand. As soon as they reach the palace, he introduces her to the queen, who is not impressed. He admits that he’s not a fan of this development either, but he must keep his promise. I love Ortoli’s version, even through the haze of Google Translate, because the queen says something like, “Keep her, she won’t take up too much space.” So far, the story has started out as a Thumbling tale, and then very briefly gone through a typical Cinderella phase with the cruel mother figure. From this point on, it is very clearly Donkeyskin. Bored by his tiny fiancée, the prince decides to throw a three-night-long ball, where he can enjoy himself with all of the most beautiful women in the kingdom. (This is softened in Manning-Sanders, where the ball is the queen’s initiative, as she hopes to distract him from his promise.) Ditu Migniulellu begs the prince to allow her to go to the ball, but he rebukes her and slaps her. After she runs to her room crying, her godmother appears. She transforms D.M. into a beautiful girl of normal stature, wearing a beautiful silk dress. She rides to the ball in a carriage drawn by butterflies (ponies in Manning-Sanders). At the ball, the prince is smitten with the transformed D.M. Teasingly, she tells him that she hails from the Kingdom of Slap, and then escapes in her tiny form. We’re going to get into this more later. The next night is an exact repeat. He kicks her with his spur, and in rose-colored silk she announces that she’s from the Kingdom of Spur. However, he also proposes to her and gives her a ring. She asks if he’s already promised to Ditu Migniulellu, but he glosses over it. From Manning-Sanders’ version:

WHAT A CHARMER. The disguised D. M. excuses herself. On the third night, her dress is blue (rainbow in Manning-Sanders) decorated with gold and diamonds, and she’s from the Kingdom of Whip, first one to guess why wins a prize. Once more she escapes, despite all his best plans, and the heartsick prince takes ill and is confined to bed. As herself, Ditu Migniulellu enters his room and tells him that she’ll make him a cake, and if he eats it, he’ll find the maiden he seeks. After some cajoling, he agrees (with the addendum that he’ll kill her if she’s trying to trick him). When she makes the cake, she slips into it the ring that he gave her at the ball. He’s delighted to find it. Then D.M., transformed and beautiful once more, stands before him, and the truth comes out. They get married and live happily ever after. She doesn’t really seem to care about his past behavior, but Manning-Sanders has the fairy godmother say a bit pointedly, “Since she loves you, she shall be yours, little as you deserve her.” Ortoli's version cracks me up here, because the prince’s most pressing question is “Can you still sing?” And then the narrator arrives too late to the wedding and is put under the table “where I received only kicks and bones. As for you, what did you do that day?” Personally, I kind of like D.M., because she has this characteristic that she never. Shuts. Up. She’s constantly chattering and singing and it seems like everybody is pretty annoyed by her. When she’s at the ball, though, she’s much more quiet and dignified. As for her prince, he is an incredibly shallow figure. He is enamored by her beautiful singing voice, and then equally repulsed by her initial appearance. Then he is so smitten with her beautiful appearance that he wishes to die if he can’t have her. His behavior towards her is uniformly horrible. When she’s in her small, despised form, he constantly scolds her for her chattering and tells her to shut up, physically attacks her, and threatens to kill her. He shows a tendency to lash out in anger against things around him like the flowerpot. In her version, Manning-Sanders tones down his threats and displaces some of his behavior (like outright planning the ball to meet other women) onto the mother. However, he is still stand-out awful. Ditu Migniulellu is different from the other variants of Donkeyskin. Like them, she is perceived as lowly and less than human. However, her appearance is not a disguise. At least, not one that she chose for herself. In this she’s more akin to the enchanted animal bride figures like Doll i’ the Grass. She is not a servant in the royal household; she is brought there as a fiancée. She never has to go through the cycle of hard physical labor. She also has a fairy godmother who gives her the dresses – an element much closer to Cinderella. Donkeyskin variants usually come up with their own dresses. In most Donkeyskin stories, the story begins with the heroine fleeing her father who wants to marry her. In Ditu Migniulellu’s case, she leaves behind a hateful mother figure who resents her and tries to imprison her. Rather than running away in disguise, like Donkeyskin, she is rescued. But once again she ends up in a situation where she is still unwanted and despised, as well as abused by the man she’s supposed to marry. Manning-Sanders’ version moves some of the blame onto the prince’s mother, but he’s still a colossal jerk. When I first read this story I was mystified by its cruel yet apparently desirable prince. Then I started reading other versions of Donkeyskin and finally found the pattern. In many versions, the love interest is physically and verbally abusive – throwing items and sometimes revealing her identity by roughly tearing off her disguise. The German Allerleirauh, or All-kinds-of-fur, had the king hurling his boots at her head. The Brothers Grimm cut this out, but allusions to it still remain within the fairytale. When I found D. L. Ashliman's site, I was saying “OHHH!” the entire time, because Ditu Migniulellu’s hints at her identity finally made a lot more sense. When the heroine appears at the ball and he asks her where she’s from, she makes up names that allude to the injuries – as in “Broomthrow, Brushthrow, Combthrow” – or in “Fair Maria Wood,” she tells him that she is from “that country that when they speak of going to a ball they are beaten on the head.” Hinty hint hint! She’s telling him that she’s from right there in his household. He doesn’t pick up on it. Fortunately, not all variants of Donkeyskin have this element. In many, the prince is kind. But why is this element of the abusive prince so widespread? Are we really supposed to cheer when they get married? One of my thoughts is that it comes from older, more accepting attitudes surrounding spousal abuse in history. But why doesn’t she just tell him who she is? Perhaps it’s a sort of test, or she’s shy. In Ditu Migniulellu, I think it’s a relic of older variants, where this element makes sense; there, due to her trauma after dealing with her father, she’s simply not ready. Others have written really in-depth on these themes.

Ditu Migniulellu clings to her prince out of a need for protection. Cruel he may be, but she needs the status and safety of marriage. She also clings to him, I think, because she is starved for affection she never got from her resentful mother. When the prince starts to renege on his promise to marry her, she dons an alternate identity to regain his attention. What strikes me most about this story is just what Ashliman pointed out—that in so many versions, she flees from one abusive situation to another. The father and husband are mirrors of each other and in many cases it’s easy to confuse them. But when you think about real life, there is a kind of answer, and a very tragic one. As Jeana Jorgensen points out, “The transition from an abusive parent to an abusive spouse, repeatedly found in ATU 510B, is reminiscent of a real-life pattern observed by therapists and caseworkers.” An interesting note from Tatar in The Hard Facts of the Grimms’ Fairy Tales: Cinderella tales have the cruel mother figure, while Donkeyskin tales have the perverted father figure. “A stepmother’s insufficient love and a father’s excessive love for a child appear to be incompatible” (149). These are usually mutually exclusive in fairytales but actually seem to dovetail really well – the father’s behavior explains the mother’s, says Tatar. Ashliman says, “This is not a story of happiness and fulfillment, but rather one of coping and surviving.” I initially thought Ditu Migniulellu was a silly and shallow tale, but it actually comes from two long traditions of folktales and has a bit of a mashup feel to it. The cruel prince that disturbed and mystified me is inherited from Donkeyskin, D.M.'s literary mother. It's a dark and disturbing history, but at the moment, I feel like I've answered a question that's bothered me ever since I cracked open the first page of this fairytale. SOURCES AND FURTHER READING

|

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed