|

"Swan Lake" and "The Little Mermaid" are the same story.

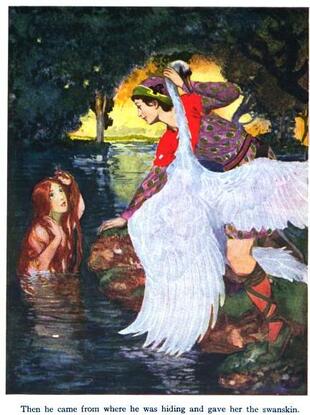

But wait, you may say. The Little Mermaid is a Danish fairytale by Hans Christian Andersen about a mermaid. Swan Lake is a Russian ballet by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, about a princess turned into a swan by a curse. In fact, both stories take inspiration from the Fairy Bride or “Quest for the Lost Bride” tale, categorized as Aarne-Thompson-Uther 400. In the Fairy Bride tale, a man takes an otherworldly creature as a wife. They live together for a while, possibly having children, but one day she leaves him and returns to her own world. This is similar to stories with a mortal woman and supernatural husband, like "Cupid and Psyche" or "East o’ the Sun and West o’ the Moon." However, while human brides usually get their supernatural husbands back, in ATU 400 - despite the title of "The Quest for the Lost Bride" - it’s less certain that a mortal husband will succeed. Many versions end with him never seeing his fairy wife again. The earliest known example is the Hindu story of Urvasi, found in the Rig Veda (c. 1200 B.C.E.). There are different types of the Fairy Bride story: A) It’s a story of spousal abduction. A man discovers a beautiful maiden - a selkie or swan maiden with a removable animal skin, or a mermaid with a magic cap. He hides the magical garment, trapping her in human form. She inevitably regains the garment and escapes as fast as she can. B) The marriage is consensual, but there is some taboo the husband must not violate (never strike his wife, never spy on her while she’s bathing, etc.). He invariably violates it, and she leaves. The most famous example is Melusine, first appearing in the Roman de Melusine by Jean d'Arras (1393). She marries a man and their union is happy at first; she builds castles for him and bears many sons. But she makes him promise never to look in at her while she's bathing. Inevitably he does so, and sees her as a half-serpent or a mermaid. When he publicly calls her a serpent, she turns into a dragon and flies away. In many versions the idea is that if he had kept his promise, she would have been freed from her curse. There's a related folktale where a young man encounters a woman who's been turned into a serpent or half-serpent by a curse. If he can kiss her three times, she will be freed and he will receive riches and her hand in marriage. Before he can kiss her a third time, he is overcome by fear and runs away. He soon regrets his cowardice, but is never able to find her again. In fact, in some versions this woman is Melusine. The maiden-turned-serpent freed by a kiss appears in many medieval sources. The story gets a tragic, inconclusive ending in The Travels of Sir John Mandeville (14th century) but a happy ending in the French romance Le Bel Inconnu (12th century) and Italian Carduino (14th century). The gender-swapped version would be the medieval story of The Knight of the Swan (tragic ending). In a further variant of B, the taboo is taking another wife. This appeared most prominently in the medieval poem of Peter von Staufenberg (c.1310). Peter's nymph mistress showers him with good fortune but gives him one condition: he must never marry anyone else, or he'll die three days after the wedding. However, other people put pressure on Peter to marry a human woman, with many telling him the nymph is a demon, and he eventually gives in. At his wedding feast, the nymph's leg appears through the ceiling. Three days later, Peter dies. The later story "Melusine im Stollenwald" combines this with Melusine and the Serpent Maiden tales; a man named Sebald promises to kiss Melusine three times to break her curse, but she becomes progressively more serpentine and dragon-like, and his courage fails him. Years later, at his wedding feast to another woman, the ceiling cracks and a drop of poison falls unseen onto Sebald's food. He eats it and dies. A snake tail is seen through the ceiling, implying that the poison is Melusine's venom. Paracelsus, a Swiss philosopher, worked both Melusine's and Peter von Staufenberg's tales into his descriptions of elemental beings in A Book on Nymphs, Sylphs, Pygmies, and Salamanders, and on the Other Spirits (published in 1566). He dubbed the water elementals "undines." German author Friedrich de la Motte Fouque spun this into a novella, Undine, published in 1811. There's another work that probably inspired Fouque: the successful Viennese play Das Donauweibchen (1798), which follows a knight named Albrecht torn between his mortal wife Bertha and water nymph lover Hulda. The plot is very different from Undine, but the love triangle, setting, and names are similar. Fouque's plot runs as follows: Boy meets water-fairy. A knight named Huldbrand goes traveling through the woods, where he meets and falls in love with the mysterious Undine. It turns out that she’s a water-spirit, and she gains a human soul by marrying him. The fidelity test. Fouque uses two taboos, straight from Paracelsus: first, the husband must never scold his nymph wife near the water or she’ll return to her own world, and second, if he ever takes another wife, the nymph will return and kill him. The doppelganger. Huldbrand reconnects with his first love Bertalda. Bertalda is, in a way, Undine's sister; she’s the long-lost daughter of Undine’s human foster parents. The tragic ending. Huldbrand breaks the first taboo by bringing up Undine's inhuman origins and berating her, causing her to disappear. He then breaks the second taboo by marrying Bertalda. Undine appears after the wedding and drowns him with her tears. When he is buried, she becomes a fountain flowing around his grave. Now we come back to "The Little Mermaid" and "Swan Lake." These stories map onto the same points as Undine. The Little Mermaid We know from Hans Christian Andersen’s letters that he was inspired by Undine when he developed the concept for “The Little Mermaid” (1837). Like Undine, the mermaid is motivated by her desire for a soul. It hits generally the same beats as Fouque's novel: Boy meets water-fairy. The mermaid saves a prince's life and falls for him. The fidelity test. The mermaid can earn a soul by marrying the prince, but if he marries someone else, she will die. The doppelganger. The prince mistakenly attributes his rescue to a human girl who physically resembles the mermaid. The tragic ending. The prince marries the other girl. On the wedding night, the mermaid is given the option to escape death by killing him. She refuses and melts into sea foam, but is resurrected as an air spirit. Swan Lake Around 1870, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky worked on an unsuccessful opera version of Undine. He destroyed most of the score, but recycled part of Undine and Huldbrand’s duet for the music of "Swan Lake," which debuted in 1877. It didn't initially do well, but in 1895 it was brought back and reworked with a simpler plot. Tchaikovsky died shortly before the new version could be completed. Boy meets water-fairy. In the 1877 version, Prince Siegfried hunts some swans until they reach a lake. There he discovers that they are fairy maidens in disguise. Odette, the leader, is the daughter of a knight and a fairy, and is in hiding from her murderous stepmother. Her grandfather, a sorcerer, gave her a magic crown to protect her, and allows her to fly freely in swan form at night. (In the updated 1895 version, Odette and her companions are humans transformed into swans by the evil genie Rothbart - a minor character in the original.) The fidelity test. Marriage will permanently protect Odette from her stepmother. Siegfried promises to marry her. (1895: Siegfried’s oath of love to Odette will break the curse, but if he marries someone else, he dooms her to remain a swan forever.) The doppelganger. Rothbart's daughter Odile, a girl who looks physically identical to Odette (played by the same ballerina). The tragic ending. Siegfried is tricked into proposing to Odile, betraying Odette in the process. Realizing his mistake, he runs back to the lake, where he tears off Odette's crown in an attempt to keep her with him. She dies in his arms and the lake swallows them both. (1895: Instead of the crown scene, Siegfried and Odette drown themselves rather than live without each other. This breaks Rothbart's power.) Inspirations and Themes Swan Lake and The Little Mermaid are not adaptations of the Undine story. They are unique works by modern authors, and Undine was just one of many inspirations behind them. Andersen was familiar with many mermaid stories. "The Little Mermaid" is unusual among the tales listed in this post, because it's entirely from the "fairy bride's" point of view. Her backstory, her feelings about immortal souls, her journey. Unlike Undine or Odette, who depend on their men to complete a test, she bears the knowledge of her test alone; her prince never has any idea what's really going on. The ending of her story, where she refuses to kill the prince, is an intentional reversal of Undine (and, in turn, "Peter von Staufenberg"). Undine easily gains an immortal soul but is still forced to obey her deadly otherworldly nature. The Little Mermaid earns a soul by rejecting that side of herself no matter the cost. "Swan Lake," on the other hand, combines Undine with the traditional swan wife folktale. There are plenty of theories about Tchaikovsky's inspirations, and plenty of European swan-shifter myths. There's the Irish story of the Children of Lir, where the main characters are transformed into swans by their wicked stepmother, and similarly "The Knight of the Swan" which, as already mentioned, has its own similarities to Melusine. (When I first started working on this blog post, the Wikipedia page for Swan Lake claimed that a fairytale called "The White Duck" could have inspired the ballet; however, the stories have nothing in common. I'm not sure where this claim came from and it's been removed anyway at this point, but I wanted to document it for posterity.) A likely influence is Johann Karl August Musäus's 1782 novella "Der geraubte Schleier" or "The Stolen Veil," itself a retelling of the swan maiden folktale. The main character, Friedbert, encounters a hermit named Benno. (“Benno” is the name of Siegfried’s best friend in Swan Lake.) The dying hermit shows him a magical pool, visited occasionally by fairies or nymphs in swan form. The nymphs gain their powers of transformation from golden crowns with attached veils. If a nymph’s crown/veil is stolen, she’ll be trapped in human form. Benno the creepy stalker hermit failed, but Friedbert succeeds in stealing one of the veils. He gives shelter to the stranded swan maiden, Callista, and convinces her to marry him. But when his mother unwittingly exposes his lies and returns the veil, Callista is furious and immediately takes off in swan form. Friedbert searches across the world until he finds her again. Despite her initial anger, she still loves him, and is so impressed by his tireless search for her that she forgives everything. So this is why Siegfried rips off Odette's crown in the original ballet - he is trying to invoke the trope that you can capture a swan maiden by taking her garment. However, Odette's crown was actually protecting both of them. Although it was later edited out, Tchaikovky's twist feels almost like a rebuttal of the way "The Stolen Veil" rewards Friedbert's selfishness. Tchaikovsky was probably also familiar with Russian fairy tales about swans. A different tale type, ATU 313 or "Girl Helps the Hero Flee," often has overlap with swan maiden tales. One example that Tchaikovsky could have encountered was "The Sea Tsar and Vasilissa the Wise" in Alexander Afanasyev's collection of Russian tales, published in the 1850s and 1860s. In this story, a prince spots the Sea Tsar's daughters as they transform from spoonbills into women. He steals the clothing of one princess, Vasilissa; however, unlike the typical fairy bride story, he relents and returns it to her, letting her fly away. Vasilissa later aids him with various magical tasks when he is imprisoned by her father. The Sea Tsar finally allows the prince to choose a bride from among his twelve identical daughters, and Vasilissa leaves clues for the prince to recognize her. Reunited, the prince and Vasilissa return to his kingdom together. In some versions, the prince then breaks a taboo and gets amnesia, and Vasilissa must crash his wedding to another woman so she can trigger his memories. The plot is very different, but notice the (double!) threat of the prince mistakenly marrying a doppelganger. Conclusion Abduction variants of the Fairy Bride tale are about control. Marriages are thinly disguised kidnappings; wives are captives who will take any opportunity to escape. On the other hand, consensual variants are about a test of trust, commitment, or courage. If the male partner passes this test, he can lift the fairy bride to a higher state of existence. Freedom from a curse for Odette, Melusine or the serpent-maiden; a human soul for Undine and the Little Mermaid. It's not a one-and-done test, either; it is long-term. The serpent maiden needs repeated kisses. Undine gets her soul early on, but Huldbrand still needs to continuously honor their vows and be a good husband. Researcher and professor Serinity Young found that the earliest recorded fairy bride stories are of divine women who lift their mortal husbands to a higher state of existence. For instance, the celestial maiden Urvasi promises her husband immortality in heaven. Young proposes that the fairy bride story in its oldest form was about marriage by abduction; Urvasi tells her mortal husband that she was miserable in their marriage, and other early versions similarly focus on the fairy bride's unhappiness and feelings of being trapped. Young suggests that as women lost social status, fairy bride stories were recast in more romantic terms. I wonder if they also blended with a separate story tradition of a cursed beast-bride or snake maiden. In addition to making the male character more sympathetic, the romantic versions also reverse the power dynamic. The mortal man is now the one holding redemptive, transformative power. This culminates in the extreme of "The Little Mermaid," written in a modern Christian European context. The Mermaid is the pursuer in her relationship, going through incredible suffering on her quest, while the prince rejects her as a romantic partner. She is the one seeking both marriage and immortality. However, despite these changes, the mortal man’s fallible nature remains from the older stories. The love rival twist is especially interesting to me. Peter von Staufenberg and Huldbrand bend to societal pressure by marrying human women, taking the easy way out. Swan Lake's Siegfried and the Little Mermaid's prince have a different dilemma. Despite good intentions, they look only at the surface, failing to truly perceive the women they love. SOURCES

Other Blog Posts Text copyright © Writing in Margins, All Rights Reserved

1 Comment

David L

6/19/2022 06:55:46 pm

This was a captivating collection to read. I found it interesting how much the culture of the author impacted the way the stories would develop, even though they had many similarities. I like your 4 part framework to show the beat for beat matches of Little Mermaid to Swan Lake. Spousal abduction sounds uncomfortable to read

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed