|

Recently, when reading fantasy, I keep running into the idea that fairies cannot lie, only tell the truth. For this reason, they must use tricky language – literal truths disguising real meanings. For example, in Holly Black's novel Ironside, a fairy says that when she tries to lie, "I feel panicked and my mind starts racing, looking for a safe way to say it. I feel like I'm suffocating. My jaw just locks. I can't make any sound come out" (p. 56).

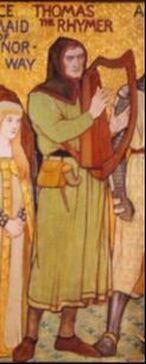

But is this really supported by older folklore? Deception seems inherent to the fairy way of life when you take into account, for instance, changelings. The core idea of changelings is that fairies are in disguise as your loved ones, pretending to be them. Why, then, is there an idea that fairies are truthful beings? Equivocating Language Trickery, loopholes, and "exact words" do play a significant part in fairytales. In the Irish tale "The Field of Boliauns," a man bullies a captive leprechaun into showing him where his gold is buried, under a particular boliaun (ragwort stalk) in a field. He doesn't have a shovel with him, so he ties a garter around the stalk and then makes the leprechaun swear not to touch it. He runs home to get the shovel, comes back, and finds that the leprechaun has taken his oath literally: he hasn't touched the garter, but has tied an identical garter around every single ragwort stalk in the field. Another case: a man carelessly trades with an otherworldly being in exchange for something which sounds inconsequential, but which turns out to be his own child. There's the giant who asks a king for "Nix, Nought, Nothing," which unbeknownst to the king is the name of his newborn son. The Grimms have "The Nixie in the Pond" with a water spirit asking for that which has just been born, and "The Girl Without Hands," where the Devil himself promises riches in exchange for what stands behind the mill; his target thinks he means an apple tree, but it's actually his daughter. This same kind of trick can happen in reverse, with a human fooling a fairy! In "The Farmer and the Boggart," a boggart lays claim to a certain farmer's field. The farmer convinces it to split the crop with him, and asks him if he would like "tops or bottoms." When the boggart says "bottoms," the farmer plants wheat, so that the boggart gets nothing but stubble. The next planting season, the infuriated boggart demands "tops" . . . so the farmer plants turnips. So we have the idea of tricky language in abundance. But what about an inability to lie? Fairies and Honesty According to John Rhys in Celtic Folklore: Welsh and Manx vol. 1, there are different classes of the Tylwyth Teg. Some are "honest and good towards mortals," while others are consummate thieves and cheats - swapping illusory money for real, and their own "wretched" offspring for human babies. They steal any milk, butter or cheese they can get their hands on. Going by context, honesty is referring to not stealing. In addition, the very dichotomy means fairies are not always honest. One term for the fairies, like the Good Folk or People of Peace, is the "Honest Folk" - daoine coire in Gaelic, and balti z'mones in Lithuanian. (Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics, Volume 5) However, these names are essentially flattery meant to avoid fairy wrath. I would avoid taking these as literal descriptors. But if you keep going, in many traditions, the fae do prize honesty. In a Welsh tale recorded by the 12th-century writer Giraldus Cambrensis, a boy named Elidorus encounters "little men of pigmy stature" - pretty much fae. "They never took an oath, for they detested nothing so much as lies. As often as they returned from our upper hemisphere, they reprobated our ambition, infidelities, and inconstancies; they had no form of public worship, being strict lovers and reverers, as it seemed, of truth." However, this is not a "can't lie," but a "won't lie." It's a moral fable, for dishonesty is Elidorus' downfall. When he tells his mother of his adventures, she asks him to bring back "a present of gold." Her request could indicate greed, but it's also a challenge for Elidorus to prove that he's telling the truth. He steals a golden ball and takes it home. For this dishonesty, the pigmies immediately punish him: he is never able to find their realm again. The 12th-century Irish legend of “The Destruction of Da Derga's Hostel" features three riders all in red, on red horses. (Red is a common fairy color.) They are later identified as "[t]hree champions who wrought falsehood in the elfmounds. This is the punishment inflicted upon them by the king of the elfmounds, to be destroyed thrice by the King of Tara." In another legend from the same era, a man named Cormac visits the sea-god Manannan mac Lir and receives a golden cup which will break into three pieces if three words of falsehood are told nearby, and mend itself if three truths are told. As Walter Evans-Wentz summed it up in The Fairy Faith in Celtic Countries, “respect for honesty” is a fairy trait in both ancient and contemporary Irish legends. Lady Wilde, in Ancient Legends, Mystic Charms, and Superstitions of Ireland, also referred to the fairies as "upright and honest" (at least in repaying debts). Another important piece of evidence is the tale of Thomas the Rhymer, with a story dating at least to a 14th-century romance. Even in the earliest versions, he is given the gift of prophecy by the fairy queen. In a later version recorded in Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border (1802), when they part, she gives him an apple while saying "Take this for thy wages, True Thomas, It will give the tongue that can never lie." Thomas points out that this will be super inconvenient, but the fairy queen does not care. Here at last is the idea of being physically unable to lie - having a mouth and a tongue that are capable only of telling truth. However, the person with this quality is a human under a fairy's spell. There's a kind of mirror image in Giraldus Cambrensis' tale of Meilyr or Melerius, another prophet, who due to his close encounters with "unclean spirits" gains the ability to detect lies. Moving on: in many traditions, divine or otherworldly beings are swift to reward honesty and punish falsehood. See “The Rough-Face Girl” (Algonquin), “Our Lady’s Child” (German), and “The Honest Woodcutter” (from Aesop’s Fables). (Aesop uses the god Mercury, but other versions of the same story sometimes use a fairy.) In the book The Adventures of Pinocchio by Carlo Collodi (1883), Pinocchio repeatedly lies to the Blue Fairy, building on multiple falsehoods. With each lie, his nose grows, until finally it's so long that he gets stuck. The laughing Fairy "allowed the puppet to cry and to roar for a good half-hour over his nose... This she did to give him a severe lesson, and to correct him of the disgraceful fault of telling lies." Only after he has been sufficiently chastised does she restore him to normal. This is the fairy-as-moral-teacher who is so strongly present in 18th- and 19th-century literature, from French salon tales to Victorian children's books. In this era, fairies (particularly fairy godmothers) were strict parental figures who demanded honesty, fairness and goodness from humans. The Ideas Combine I think the seeds of the modern idea of fairies and falsehood come from the famed British folklorist Katharine Briggs. In The Fairies in Tradition and Literature (1967), Briggs recounted that "According to Elidurus the fairies were great lovers and respecters of truth, and indeed it is not wise to attempt to deceive them, nor will they ever tell a direct lie or break a direct promise, though they may often distort it. The Devil himself is more apt to prevaricate than to lie..." (pp. 131-132). There are a couple of different things to take from this. One is that not only do fairies not lie, but it's equally important for humans to be honest with them. "To tell lies to devils, ghosts or fairies was to put oneself into their power" (pp. 222-223). Also, it is clear that at least one of her main sources for this theme is Elidurus. She referenced Elidurus again in Dictionary of Fairies (1971), where she mentions again that fairies "seem to have a disinterested love" of truth, and that it is unwise to lie to them, although they may use tricky language themselves. She is summarizing based on a combination of two tale types - one where fairies value honesty, and one where they trick and evade. I have been collecting examples of books where fairies speak only truth. The earliest example so far is the children's book series Circle of Magic by James MacDonald and Debra Doyle. All six books were published in 1990. In this world, wizards cannot lie or they will corrupt their own power, but it is possible to use misleading language. The restriction is strongest for the elves or fair folk. According to their ruler, the Erlking: "You [a wizard] cannot speak an untruth and expect magic to serve you truly thereafter. Here magic is purer, and far more strict a master. A mortal wizard can sometimes break the words of a promise in order to keep its spirit, but I cannot. If I say that I will do a thing, or that I will not do a thing - then I must do it, or leave it undone, exactly as the words were spoken." (The High King's Daughter, p. 22) The examples I've collected really pick up after the year 2000. In Buttercup Baby by Karen Fox (2001), the faery protagonist has physical difficulty with telling actual lies (p. 218). It's also a big theme in the Dresden Files, for instance Summer Knight by Jim Butcher (2002), where not only are faeries not "allowed" to lie, but they are "bound to fulfill a promise spoken thrice." (p. 194) In Holly Black's Tithe (2002), there is a brief mention of "no lies, no deception" in the realm of fairies. Black goes more in-depth with later books, starting with Valiant (2005), where fairies are physically incapable of falsehood. A running theme is that they covet humans' ability to tell outright falsehoods. Other examples: Melissa Marr's Wicked Lovely series and Cassandra Clare's Shadowhunters (both beginning 2007). Patricia Briggs' Mercy Thompson series hints that if fairies lie, something bad will happen to them. Holly Black frequently references and recommends Briggs' work (as in this tweet). Patricia Briggs (no relation) was also inspired by Katharine Briggs, mentioning her work in an interview here. Morgan Daimler's Guide to the Celtic Fair Folk (2017) is a recent compendium that cites Katharine Briggs when saying that fairies are "always strictly honest with their words." Conclusion The idea that fairies cannot lie is a creative modern twist, stemming from cautionary fables about honesty and from stories about using wordplay to get the upper hand. Katharine Briggs never says that fairies cannot lie. She says only that they do not lie, apparently out of a strict moral code. My current theory is that a semantic shift occurred sometime between The Fairies in Tradition and Literature in 1967 and the Circle of Magic series in 1990. This shows how fairy mythology is still growing and evolving today. In older tales, from the honest woodcutter who meets the god Mercury, to Elidurus, to Pinocchio, otherworldly beings - including fairies - deeply value honesty. But it’s not just that fairies may not (technically) lie to you. It’s that you shouldn’t lie to them. But unvarnished truth isn’t always the best idea either, if you read tales like "The Fairies’ Midwife" . . . Thus the importance of tactical wordplay. Do you have any other examples of stories on fairies' relationship with honesty? Share them in the comments! [Edit 1/14/21]: Another one for the list is a German tale, "The Silver Bell" (Das Silberglöckchen), found in Arndt’s Fairy Tales from the Isle of Rügen (1896). Arndt explains that "the little folks [Unterirdischen, literally Underground Ones] may not lie, but must keep their word and fulfil the promises they give, else they are at once changed into the nastiest beasts, toads, snakes, dung-beetles, wolves, lynxes, and monkeys, and have to crawl and rove about for a thousand years, ere they can be delivered; therefore they hate lies." As in the Irish examples, the fairies are physically capable of lying, but fear punishment; and honesty extends not only to telling the truth, but to oaths and other matters of honor. The exact source for this punishment remains unclear. Text copyright © Writing in Margins, All Rights Reserved

3 Comments

Sieran

7/20/2020 10:11:33 am

Thanks for the article. I started reading a series set mainly in faerie, where the faeries can lie. (M.A. Grant's The Darkest Court series). This bothered me a lot, since I believed (mostly from reading Cassandra Clare and Holly Black) that faeries were unable to lie, or that they would suffer from severe pain if they do lie. I read some of the Dresden files, too, which might have also swayed me to believe that faeries can't lie or would suffer if they do.

Reply

Writing in Margins

7/20/2020 12:31:09 pm

Thanks for the comment. It's really interesting how popular this idea has become! I'll have to check out M.A. Grant's books.

Reply

JS de Beer

2/6/2021 01:58:02 am

A thorough and thoughtful article ... thank you! I have the impression in some stories that fairies are bound only by individual promises, not by universal moral laws. That is how Susanna Clarke portrays them in Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell (2004).

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed