|

Today, if you search around on the Internet, you may encounter the idea that Titania and Mab are opposing queens, representing Summer and Winter Courts or "Seelie and Unseelie" Courts. I've even found the claim that this is drawn from ancient legend - but is that true? There is also a common idea that Mab as queen of fairies is somehow older than Titania. In 1993, The New Encyclopaedia Britannica claimed that Mab's "place as queen of the fairies in English folklore was eventually taken over by Titania." The entry is misleading, as we will see that both Mab and Titania are Shakespeare's creations. If you go back to the source, Mab may not be a queen at all. It was in literature after Shakespeare that Mab usurped the place of the more regal and powerful Titania as Oberon's wife.

Around Shakespeare’s time - just before, and just after - fairy queen characters showed up under varied names: Gloriana, Chloris, Aureola, Caelia. Proserpina, or Persephone, was sometimes the leading lady. In grimoires, there were Micol and Sybillia. There was also the old medieval tradition of a queen of witches or fairies, who led her followers in a midnight revel traveling across the world. This figure might be known as Herodias, Diana, or a thousand variations. However, perhaps most often, fairy queens were nameless figures. William Shakespeare changed that. A Midsummer Night's Dream and Romeo and Juliet were both likely composed sometime in the mid-1590s. Which came first? That's up for debate. But it seems generally agreed that they were written within a few years of each other. Titania A Midsummer Night's Dream featured Oberon and Titania as godlike figures. Although their subjects were miniscule beings who tended flowers and could hide inside acorn cups, the rulers commanded the weather and hailed from far-flung realms like India. "Proud Titania" has human worshippers, and with her husband she holds sway over the four seasons. Her romances with humans imply that she is of roughly human scale. The name "Titania" or "Titanis" appeared in Ovid's Metamorphoses as an epithet for several goddesses who were descendants of Titans. One "Titania" is Circe, a sorceress who transforms men into beasts. Another is Diana, who is called Titania while bathing in a woodland pond within a sacred grove. When a man sees her naked, she transforms him into a stag to be torn apart by his own hunting hounds. Both of these scenes are echoed in Shakespeare's character Bottom, whose head is switched for a donkey's, and with whom a magically roofied Titania falls in love. Diana was a Roman goddess, equivalent to the Greek Artemis - goddess of the moon, the hunt, wild animals, and unwed girls. The wilderness and the night are both fitting associations for a fairy queen. However, it also brings to mind the medieval Diana as leader of a nighttime witches' revel. James VI's Daemonologie (1597) said that "Diana and her wandering court . . . amongst us is called Fairy . . . or our good neighbours." Diana has ties to Hecate, and Hecate to Persephone. So Titania is a super-combo of classical and medieval references – Artemis, Circe, Hecate, Persephone. Goddesses of night, nature, the underworld, witchcraft, and transformation. Titania is not the only reference here to Ovid; the play also features the story of Pyramus and Thisbe. Honestly, the play is set in the time of Greek myth and features the hero Theseus. Mab Romeo and Juliet featured a very different fairy queen. She does not appear onstage, but is described in jest. "Queen Mab" is "the fairies' midwife." She is also the "hag" who presses people as they sleep - making her a nightmare or succubus. Hag was a common name for this type of spirit. Mab is a being on bug scale, who as a midwife brings forth not children, but dreams, sex dreams and nightmares. She does ride at night, like some older fairy queens, but her passage is through people's minds, "through lovers' brains." She is so tiny that her ride is not a rampage through forests and air, but over people’s lips or fingers. Her physical actions consist of tickling noses, tangling hair in knots, and delivering blisters or cold sores. There have been numerous suggestions for Mab's etymology. Mab is Welsh for "child," tying to her small size.

Mab comes from Medb or Maeve, an imposing warrior queen of Irish mythology. This is perhaps the most commonly cited explanation: Goddess-queen Medb evolved into Fairy Queen Mab.

Mab is connected to the medieval French "Domina Abundia" or "Dame Habonde." Her name means "Lady Abundance." According to William of Auvergne (d. 1249), Domina Abundia and her attendants were believed to enter houses at night and bless anyone who left out food for them - a lot like the Diana/Herodias figure. The M would have been added in the same way you get Ned from Edward, etc., or perhaps from "Dame Abonde" running together into one word.

Wirt Sikes wrote in 1880 that the queen of the Welsh ellyllon (tiny elves) was none other than Mab, and thus Shakespeare must have gotten Mab from "his Welsh informant."

Mab is short for "Amabilis," or lovable.

There is another option. Before Romeo and Juliet, there was a play titled The Historie of Jacob and Esau. This play, performed in 1558 and published in 1568, featured a midwife named Deborra, who is called a witch, a "heg" (hag), "Tib" (a typical name for lower-class English woman, used to mean girl, sweetheart, or prostitute), and finally Mab - "thou mother Mab... olde rotten witche." Queen Mab is a hag and a midwife . . . just like Deborra. She is not a teeny-tiny Medb or Dame Abonde, but she is a teeny-tiny Deborra. In fact, is Queen Mab a queen? Or is she a quean - a word for either a woman or a prostitute? This fits with the sexual innuendo throughout the passage. It also makes more sense than a member of royalty working at such a job as midwifery. Other than her title, she is not queenly in the slightest. She's identified as "the fairies' midwife," not "the fairies' queen." We do not see her in any kind of leadership role, as we do Titania. Jennifer Ailes even suggests that Mab is never directly identified as a fairy or a [royal] queen. She is just the fairies' midwife - and there is a large body of tales with titles like "The Fairy's Midwife," where fairies do not go to one of their own for help with childbirth, but to a human. Clearly Mab is not human, but just because she is the fairies' midwife does not mean she is a fairy herself. In addition, "Mab" was a word for a slattern or dirty, unkempt woman, dating to the 1550s. Ailes suggests that "Mother Mab" was a traditional name for a witch, explaining why it was used for Deborra. Or maybe Mab was simply a nickname for a dirty, slovenly woman. So then, Queen Mab's name might be simply "Mistress Slattern" or "Mrs. Lazybones." This “mab” could be derived from Mabel – much as the girls’ name Tib (possibly short for Isabel) gained similar connotations. In Elizabethan times, "Tom and Tib" were common names used to mean boy and girl, much like Jack and Jill. Tib became a generic word for girl, sweetheart or prostitute. Tib is another name used for Deborra. Incidentally, around the 1630s, a fairy named Tib shows up independently in the Mad Pranks and Merry Jests of Robin Goodfellow, and in the poem Nymphidia. Both Tibs are close to the leadership ranks – at least, Robin Goodfellow’s Tib is one of the chief female fairies, and Nymphidia’s Tib is one of the fairy queen’s maids of honor. Also, both Tibs are part of a team of fairies with rhythmic, monosyllabic names – “Sib and Tib, and Licke and Lull” in the first, and “Fib and Tib, and Pink and Pin, Tick and Quick,” etc., etc. in the second. So, two things: first, this was the fashion for fairy names at the time. Second, it was quite common for a generic human name to be applied to an otherworldly being. Another example is Thomas, seen as Tom Thumb, Tam Lin, Tom Tit Tot, and Thomas the Feary. Shakespeare was the apparent tipping point in a huge fad of tiny fairies. Previously, fairies had been either human-scale or the size of children - the old Oberon, of Huon fame, was three feet tall. But now everyone was jumping on the bandwagon with flowery poetry about fairies who, unlike their folkloric ancestors, were practically jokes. They were far too small to be effectual at anything. They skipped about and hid inside flowers. Oberon remained as the fairy king. However, the goddess-like Titania did not accompany him. Instead, as Thomas Keightley said, Mab was such a hit that she "completely dethroned Titania." The wee lady called "Queen" who rode in a hazelnut-shell chariot was the only fitting empress for this generation of fairy. The first known sign of this was in Ben Jonson's Entertainment at Althorp, presented to Queen Anne in 1603. In this performance, Queen Mab and her attendants welcome the queen. She is described as a prankster, like Shakespeare's Mab - she "rob[s] the dairy" and partakes in typical fairy mischief, but she also has regal associations. She is undeniably queen and ruler of the fairies. She pays homage to Anne as previous fairy queens did to her predecessor, Elizabeth. In a similar masque years before, fairy queen "Aureola" gave Elizabeth a flowery garland; in this one, stage directions call for Mab to give Anne a "jewel." In literature, Elizabeth was obeyed by and represented by fairy queens. Now it was Anne's turn. Mab was not yet paired with Oberon, but that was soon to come - in "Nymphidia," a mock-epic poem by Michael Drayton, published in 1627. Here again we have Oberon and Puck running around with lots of furor over romance... but Oberon's queen is Mab. Many of the fairies in this play have cutesy monosyllabic names (like Tib); this may be why Drayton leaned towards Mab. Her name fit his style. Drayton also mentioned Mab in his work "The Muses Elyzium." Despite the comedy of their tiny size, there is still a touch of fear to the fairies, with reminders that Mab is really a succubus. Robert Herrick followed suit in the 1620s and 1630s with many fairy poems. Oberon and Mab feature together in "The beggar to Mab, the Fairy Queen," and in the rather disturbing "Oberon's Palace." As in Nymphidia, there is an eerie sense with these fairies, whose palaces are crafted from the body parts of humans, animals and insects. In following years, Mab continued to be a hit, appearing as Oberon's consort in:

Newcastle and Randolph give the longest descriptions of Mab and Oberon; the others are just brief mentions, with no explanations necessary, for Mab was familiar enough to their audiences as the Fairy Queen. As time went on, Mab continued to be instantly recognizable. She was mentioned in Peter Pan, for instance. Such is Mab's ubiquity that she could be the ancient, evil queen of the Old Magic in the 1998 TV miniseries Merlin, while also the benevolent monarch of the pixies in the 1999 film FairyTale: A True Story. On that note, back to Titania. After her adventure in A Midsummer Night's Dream, her history was much less busy than Mab's. She didn't capture the popular mind the way Mab did. There were a few exceptions. She was the fairy queen in Dekker's work "The Whore of Babylon" in 1607, and in The Changeling, a 1622 play by Thomas Middleton and William Rowley. She also appeared in the heavily Shakespeare-based masque "The Fairy Favour" by Thomas Hull (1766). Like Mab, Titania apparently made it into at least some oral folklore. In Thomas Pennant’s 1772 book Tour in Scotland, and voyage to the Hebrides, Titania is identified not only as queen of fairies and wife of Oberon, but as the “ben-shi,” literally “fairy woman,” who gave the MacLeod clan a blessed Fairy Flag. She made a comeback as centuries passed, not really becoming popular until around the Victorian era, when she began regaining her status as Oberon's consort in literature and other media. She appeared in Christoph Martin Wieland’s 1780 poem Oberon, based on both the Midsummer Night’s Dream and the Huon narrative. This influential poem was adapted several times, including into an opera. She was also in the comic opera A Princess of Kensington (1903). This was also the era when Titania and Mab both began showing up in the same stories. There was some waffling over whether the two were interchangeable. "We have noticed the general name given to the queen of the fairies, that of Titania; we must not forget that she was sometimes called Mab," according to Henry Christmas, writing in 1841. John Ogilvie's Imperial Dictionary (1859) concludes that Oberon's "wife's name was Titania or Mab." An article in the 1910 Fortnightly Review questioned if Titania and Mab were the same being or not, but seemed to tend towards "yes." In 1847, in The People's Journal, W. Cooke Stafford suggested that Mab was queen of "dark spirits" of the night, and Titania rules the "superior intelligences" (?) who do not fear sunlight. This is the closest I've seen so far to Mab and Titania being queens of dark and light or whatever. According to The Century Dictionary in 1895, "Titania, the fairy queen, is not the same person" as Mab. Even more audacious, Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable (1898) listed Mab as “the faries’ [sic] midwife. Sometimes incorrectly called queen of the fairies." On to Titania and Mab appearing in the same works: The Sloane Manuscript 1727 (a 17th-century manuscript in the British Museum) includes a treatise on magic. Katharine Briggs quoted it describing the "treasures of the earth" as "florella, Mical, Tytan, Mabb lady to the queene." The queen whom "Mabb" serves may be Mical or Micol, who is called "regina pigmeorum" in the same book. Tytan and Mabb recall Titania and Mab. In particular, Titan, Titem and other variations were often invoked in grimoires. In Thomas Hood's 1827 poem "The Plea of the Midsummer Fairies," both Mab and Titania make an appearance, and in 1876, both appeared in in the story "Titania's Farewell" in The Case of Mr Lucraft and Other Tales. In these tales, Mab is a queen, but apparently subordinate to Titania, who is the real queen bee. (Their positions are flipped in the 1913 play "A Good Little Devil" by Rosemond Gerard and Maurice Rostand, later turned into a film starring Mary Pickford.) Titania and Mab were at odds for perhaps the first time in Camilla Crosland's 1866 children's book The Island of the Rainbow. Here Queen Titania is the wise and gracious queen of the fairies, while "Quean Mab" is a "little spiteful mischievous old Fairy - who, by the bye, must herself have put it into the heads of mortals that she was a Queen." Mab is actually on trial when she appears in the book. Of course by this point in time, being written for children, any good fairies must distance themselves from traditional fairy activities of spoiling milk or making mischief. Still, it seems a little ironic when Mab is the one accused of these crimes, while Puck is a humble servant to the morally upright Titania. So what about Titania and Mab as leaders of opposing forces? I think the idea has its basis in a new movement towards classifying all these folktales. Researchers in the 19th and 20th centuries - like William Butler Yeats, Wirt Sikes, and Katharine Mary Briggs - became concerned with categorizing fairies. This moved into fiction, as authors began breaking up fairies into categories. Good and evil. Light and dark. Seelie and unseelie (drawing on a Scottish fairy term meaning essentially "blessed people"). Or summer and winter. As for Titania and Mab being the leaders: I tried to track this idea through published books. Here is what I have found:

The idea of opposing fairy courts known as Summer and Winter or Seelie and Unseelie has also become very prevalent in recent literature. I can think of multiple YA novel examples from the past 20 years. Another common idea is that Mab was the first fairy queen, and that Titania is her successor. This has appeared in extra-canonical materials for the 90's TV show Gargoyles, as well as the novels God Save the Queen by Mike Carey (2009) and The Treachery of Beautiful Things by Ruth Long (2013). To sum up: Titania and Mab as counterparts or enemies is a new idea. Both were created by Shakespeare around the same time, but served very different roles. They weren't even opposing roles - just unique. Titania, inspired by classical Greek goddesses, was a queenly nature deity. Mab, based on stereotypical English midwives and the idea of the nightmare demon, was a microscopic hag who delivered dreams instead of babies. However, unlike Titania Mab entered popular culture from the beginning. She tied in better with fashions of the time. She even usurped Titania's place as Oberon's bride; he was the archetypal fairy king even before Shakespeare, and Mab became the archetypal fairy queen. I wonder if even royal themes at the time at something to do with it - Mab's name is the same number of syllables as Queen Anne, and one of Mab's most important early appearances was in a play for Anne. Meanwhile, Titania made a comeback around the time of Queen Victoria. Today, the idea of the two Shakespearean fairy queens as rivals has been popularized by authors like Jim Butcher. Titania, who appears in A Midsummer Night's Dream, and who proclaims "The summer still doth tend upon my state" is the clear front-runner for summer (even though she really oversees all seasons). For a counterpart, why not Mab, who is equally Shakespearean and has associations with nightmares and mischief? Do you know of other sources where Titania and Mab are either the same person, or diametrically opposed? Leave a comment! Sources

6 Comments

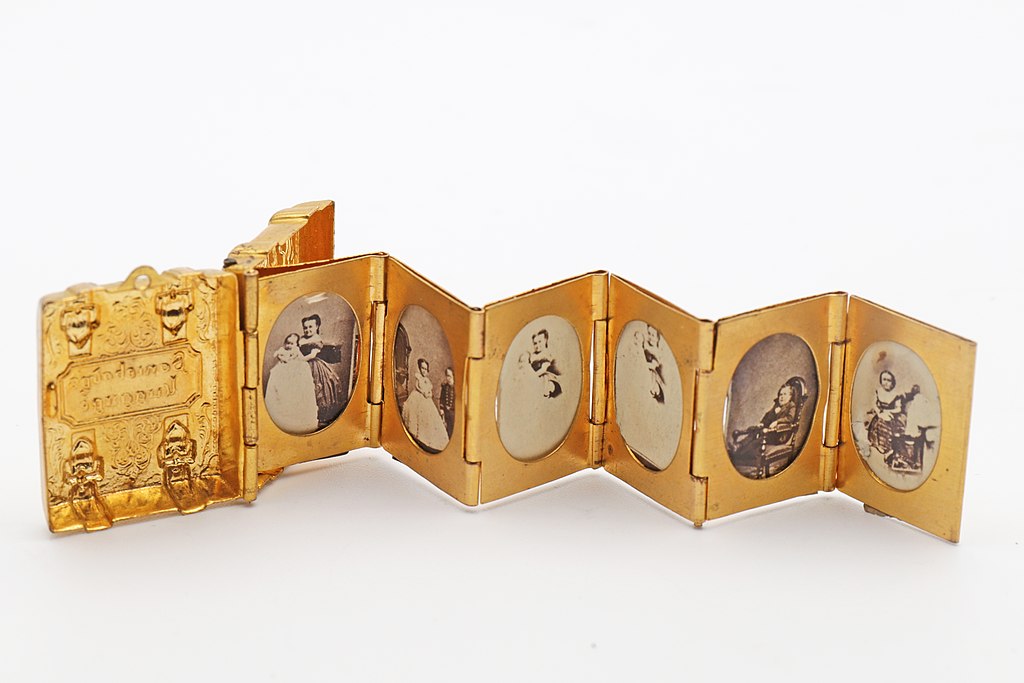

If there's one historical mystery I'm dying to know the answer to, it's what was going on with General Tom Thumb's baby. The baby hoax has become one in a long litany of P. T. Barnum's frauds and humbugs. To cut a long story short, two of his performers, under the stage names General and Mrs. Tom Thumb, posed with a baby and performed with it to fake the impression that they had had a child. One website I encountered suggested that as part of the offensive hoax, a different baby was used for every single publicity photo. Another took the opposite tack: that the Thumbs really had a daughter, but that another baby was borrowed for photos because the real baby wasn't "photogenic" enough. Confusion abounds. So now, I'm going to take a plunge into the actual news articles from the time.

Charles Sherwood Stratton, or General Tom Thumb, began his life as one of Barnum's most famous performers when he was about four years old. He and his wife Lavinia Warren - who Barnum "discovered" when she was 21 and Charles 25 - were little people. In December 1862, to drum up attention, Barnum coyly published letters dated December 1862, where he begged Lavinia to come work with him. This method seems to have worked well. In January 1863, Harper's Weekly raved about Lavinia's first appearance and crowed, "General Tom Thumb and Commodore Nutt are henceforth not without hope." From her first appearance, people were trying to pair her off. The showrunners wasted no time. Her wedding to General Tom Thumb was the following month, in February. The New York Times had all the details, from the design of Lavinia's gown to the list of wedding gifts - “all of which were very nice, excepting the common affair of a cradel [sic] with which some person of little wit and less modesty encumbered the table.” For contemporaries, the idea of the Strattons reproducing was both engrossing and taboo. In the Sketch of the life, personal appearance, character and manners of Charles S. Stratton, the man in miniature, known as General Tom Thumb, and his wife, Lavinia Warren Stratton, an 1863 pamphlet possibly penned by Barnum himself, the Strattons were called a "mimic miniature Adam and Eve." The writer pondered whether they should be "the inventors of a race of humanity which . . . shall grow small by degrees." The Strattons began entertaining, giving their "levees" and often posing in their wedding costumes. They worked with fellow performer Commodore Nutt and Lavinia's younger sister Minnie. However, the rumors had begun, which was doubtlessly what Barnum had hoped for all along. On 15 December 1863, the South Australian Register noted, "The American papers record that the wife of General Tom Thumb is enceinte." The Strattons were performing through November, December and January. The New York Reformer. February 09, 1864. "Mrs. Gen. Tom Thumb became a mother a few weeks since. Tom is said to have danced a hornpipe at the announcement." The Daily Ohio Statesman. February 16, 1864. “‘Mrs. Tom Thumb,’ says the Boston Post, ‘is a mother.’ ‘The Post is more premature than the Princess of Wales,’ responds the Cincinnati Commercial, and says to the Post--”Don’t be in a hurry about the little Thumb.’ Of course the Commercial knows, or ought to know, all about the delicate point, as Mrs. Thumb is on exhibition in that city.” The Quad-City Times, Davenport, Iowa. February 20, 1864. "Mrs. General Tom Thumb is reported to have become a mother, to the great joy of the General." Tri-states Union. March 4, 1864. "If the report be true, why, look out for a profitable show in six or eight months - Tom Thumb, and Tom Thumb's Wife, and Tom Thumb's Wife's Baby!" Liverpool Mercury, etc. Tuesday, March 8, 1864. "The wife of General Tom Thumb was delivered of a son and heir on the 22nd of January.” The Sacramento Daily Union, March 14, 1864. "Mrs. General Tom Thumb, it is said, gave birth to a child on the 12th of January." The Burlington Weekly Sentinel. March 18, 1864. "The newspapers (scaly fellows) report that Mrs. Gen. Tom Thumb was -- and has --. It turns out, however, to be a hoax... So Tom didn't dance the hornpipe after all, as was reported. In other words, there isn't any little Thumb yet." The Troy Weekly Times, March 19, 1864. "A Connecticut paper [Charles was from Connecticut] says that 'the statement which has appeared in numerous journals to the effect that Mrs. Tom Thumb had become a mother is somewhat premature as we are assured upon the very best authority that the great event is not expected to occur before the month of July next.'" Rumors flew from place to place, varying from paper to paper and by word of mouth. The baby might be a boy. The birth might have occurred in January, or it might be expected in July. During all this, the Strattons were apparently still performing. In October 1864, the troupe departed for a tour in England. They arrived in Liverpool on the steamship City of Washington, and with them was their baby. The Daily Post from Liverpool reported on November 12th, 1864, that the Strattons were accompanied by their "infant daughter" who would be "twelve months old on the 5th of December." The birthdate could just be the result of careless reporting. However, Barnum had advertised a five-year-old Charles as an older child to make him seem smaller. Maybe this was the same principle. All that aside, December 5, 1863, was the official birth date for the Thumb baby. A medal produced by the Barnum Museum shows an image of the family trio, and refers to the Strattons' daughter with that birthdate. The Sketch of the Lives of C. S. Stratton and his wife, etc (1865) repeats this: "On the 5th of December, 1863, Mrs. Stratton gave birth to a female infant, weighing at the time of its birth but three pounds." The baby was an instant hit, but the main question was how big she was. Charles and Lavinia were both average-sized infants but stopped growing at a young age. It would have been impossible to say whether the baby was done growing. Everyone had an opinion, though. The Morning Post in London said that she "partakes of the proportions of her parents." The Lancet wrote "The diminutive pair seem very proud of their offspring; whether it will be of the same Liliputian stamp we cannot at present say." And the Morning Herald called the child "heiress to the Stratton name and fortune, but not to the Thumb inches, if we may judge by present looks, for the little girl (called Minnie, after her aunt) is just a year old and already weighs 7 3/4 lbs." In the midst of all this, the baby had a name: Minnie Stratton, after Lavinia's beloved sister and fellow performer. On November 24, 1864, the Morning Post in London reported the Tom Thumb company's visit to the Prince and Princess of Wales. "The Princess of Wales bestowed much attention on the pretty little infant." The baby was "a pretty little girl, with light silken hair and a vivacious disposition," according to the Soldiers' Journal on December 14, 1864. The London Daily News, on December 20 1864, reported the Thumb party's performance at the Crystal Palace, where Baby Minnie was a hit. "The ladies enjoyed the luxury of a close inspection of the General's baby, and of overwhelming the poor little thing, much to its annoyance, with kisses." The reporter seems taken with the comedy of Charles Stratton being defeated by a fretful baby: "He made several valiant attempts to induce her to put on a pair of gloves nearly an inch long, and when at last he had had his ears sufficiently boxed, and the gloves thrown in his face for his pains, he made a very skilful retreat, and left the baby in possession of the field. " The reporter also remarked on the resemblance of the child to her parents. The advertisements continued, milking the Stratton family image for all it was worth. A letter published in the Times-Picayune in January 1865, and in the Santa Fe Weekly Post, in February 1865, described meeting the performers in Paris. The description of Minnie Stratton ends on an odd note. "[T]he lion of the party was the baby, a little girl twelve months old, looking the picture of health and, without exaggeration, extremely beautiful. The face has nothing of the dwarf about it, but my observation that she looked as big as an ordinary child of her age was not approved by the secretary, who assured me that the weight was something very far below the average, and, lifting up the expensive lace frock, showed me her little feet in red morocco shoes, which are not larger than those of a moderate sized doll. My inquiry whether the child was expected to grow up a dwarf, met with the cautious answer that there was 'no precedent.' This is, I believe, true. There is, I am pretty sure, no instance of such a small child as Tom Thumb and his wife having been the progenitors of a child. I venture to prophecy, however, that Miss Minnie Stratton (that is the name of the infant) will, if she lives to attain her majority, be nearer the ordinary size of mankind than that of her parents. I do not believe in the foundation of a race of pigmies." In August 1865, the Sacramento Daily Union reported on the party's visit to Windsor Castle, and actually gave an idea of what their performances were like. "The performance commenced shortly before four o'clock, being opened by Mrs. Tom Thumb with a song, "My Native Land." This was followed by "Impersonations of Billy O'Rourke" and "Napoleon Bonaparte" by General Tom Thumb. Mrs. Stratton, the General's wife, then introduced her infant daughter." The baby was yet another part of the act, to be brought out, passed around and cooed over between songs and jokes. But it was not to last. The Morning Post reported on 26 September 1866 that "Yesterday Minnie Stratton— or, as the child used to call herself, Minnie Tom Thumb— the infant daughter of General and Mrs. Tom Thumb, died at the Norfolk Hotel, Norwich." She would have been roughly two years old. The Norfolk News reported on her burial in the local cemetery. Cause of death was given as "gastric fever;" other papers reported it as "inflammation of the brain." Although the funeral was supposed to be private, it was mobbed by about a thousand people. "It is said to be the intention the General to apply for an order to have the corpse removed to America, his native land, when he himself returns.” The grave still stands in the Norfolk cemetery, and Minnie is listed in the local death records as the daughter of Charles Stratton. Newspapers reported cancellations of performances "owing to the death of little Minnie Stratton." The Strattons' fellow performers Commodore Nutt and Minnie Warren were on their own for several shows. Minnie Stratton's death was treated seriously. And that was it. The party went back to performing. In July 1878, Minnie Warren died in childbirth. Her baby, who also died, weighed six pounds. According to obituaries, Minnie had expected a miniature baby and sewed clothes based on doll patterns, "one-sixth the size of garments for ordinary babies." Her husband, however, as well as P.T. Barnum, had been apprehensive, according to the news. One obituary for Minnie Warren mentioned "the memory of the spurious Thumb baby." At this point, at least some Americans had decided that Minnie Stratton - whose heyday took place an ocean away - was a hoax. But the troupe itself made no such admission. Sylvester Bleeker, the Strattons' manager for many years, gave an 1882 interview mentioning the child. "Mrs. General Tom Thumb's baby was one of the prettiest little girls I have ever seen...It was a perfect picture of Minnie Warren, Mrs. Thumb's sister, and everybody knows how beautiful she was. Lavinia Warren was married to Charles S. Stratton (Gen. Tom Thumb) in 1863... The baby was born a year after, and the event was heralded all over the world. The child was like other children in size, but was prettier than the average, and was healthy and bright. Mrs. Thumb idolized her baby, and when death took it from her, the blow was almost more than she could bear. The little girl lived to be two years and eight months old, and died of gastric fever in Norwich, England. She was made a great pet by the English ladies, who were in the habit of giving her sweet meats and candies, and I think this was one of the causes that led to little Minnie's death." Charles Stratton's obituary in the New York Times, published July 1883, mentioned that "He had one child, born in Brooklyn 14 years ago, who only lived two years. It was of ordinary size.” (This would place the child’s birth in 1869 and death in 1871.) An odd sidenote: the Galveston Daily News, in August 1892, reported the wedding of another couple of performers with dwarfism. There, the writer mentioned in passing "They say . . . that Tom Thumb's son is nearly 6 feet high and that he is very proud of his little mother.” Then, in April 1901, an article was published in several papers titled "Tom Thumb's Widow Reveals Secrets of the Show." It claims that about a year after the Strattons' wedding: "an innocent little item was smuggled into the English papers to the effect that the Tom Thumbs had A Baby Son. It was widely copied, and by the time Mr. Barnum and his midget charges arrived the British public was worked up to a considerable degree of expectancy as regarded the baby. In Egyptian Hall, London, they were exhibited all over again - General Thumb, Mrs. Thumb, and the baby. The performance was repeated all over Europe, and the Thumbs came back richer than they had ever been before. People have occasionally wondered since then whatever became of that baby! ... "I never had a baby," [Lavinia] declared recently. “The Exhibition Baby came from a foundling hospital in the the first place, and was renewed as often as we found it necessary. A real baby would have grown. Our first baby - a boy - grew very rapidly. At the age of four years he was taller than his father. This would never do... We appealed to Mr. Barnum. He agreed with us. He thought our baby should not grow. Thus we exhibited English babies in England, French babies in France, and German babies in Germany. It was - they were - a great success." This article is widely quoted, but does nothing but raise questions. Early reports did say that they had a son - but when they went touring, it was with a baby girl. This also implies they paraded around with a baby for over 4 years. They were married at the beginning of 1863 and could not have debuted their baby until at least November 1863. The baby's death was announced in England in September 1866. There wasn't time for a baby boy to grow to age four and for more babies to follow. Something here is fishy. Was Lavinia misremembering her past?What was going on here? And "taller than his father"? This phrase is reminiscent of the declaration that Minnie Stratton, age one, weighed “7 ¾ lbs., which we take it is more than her father weighed at the same age.” That’s as much as an average newborn weighs today, so I’m not sure what they were trying to say there. It is clear that the marketing team was trying to push the idea that the baby was unusually small, but observers were not always convinced and there was some arguing over whether the baby would grow. Now we’ve got an affirmation that the baby did indeed grow. Or is this line, perhaps, an echo of the rumor that Tom Thumb’s son grew up to be six feet tall? Lavinia would be of no further help. In 1906, she wrote a series of five articles for the New York Tribune Sunday Magazine, and went on to publish an autobiography. She never mentioned the baby, though she included many details about her tour through Europe beginning in 1864. That year, newspapers had made much of the baby - but in Lavinia's account, there's not even a hint of any baby's existence. No real baby, no hoax baby. No babies whatsoever, except for her sister's tragic pregnancy. In April 1946, Edna L. Bump - wife of Lavinia's nephew Benjamin J. Bump - wrote a letter to the editor of New York Times regarding an article on the Strattons. "The Tom Thumbs never had a child. The child shown in that picture was borrowed for a publicity stunt when they were employed by Barnum." Benjamin mentioned the baby hoax in his own pamphlet about the Strattons, "The Story that Never Grows Old," in 1953. Alice Curtis Desmond, in her 1954 book Barnum Presents General Tom Thumb, quoted Benjamin on this strange "family secret." In Desmond's account, Barnum was solely responsible for the hoax. "He hired infants wherever the circus happened to be, with their mothers as nursemaids" (page 215). (Note that these are not foundling hospital babies; their parents are along for the ride.) Here, Lavinia was a victim of the hoax, broken-hearted by her inability to have a child. Gradually, this new narrative spread. People stopped mentioning a child born to General Tom Thumb, and instead told the story of a manipulative baby-exploiting hoax. The rediscovery of Minnie Stratton's grave and death records came as a shock when publicized in the BBC documentary The Real Tom Thumb: History's Smallest Superstar (2014). One online article declares that the baby in the photographs was actually Lavinia's nephew "Gus." I have been unable to find any support for this suggestion. However, with research through ancestry.com, I did learn that Lavinia had a nephew named William Sherwood Wilbar, or Willie, born to her sister Sarah on May 9, 1864. The same time as those birth rumors. There’s nothing to indicate that William ever posed as the Strattons’ child for photos. However, it’s intriguing that he shared a middle name with Charles. Could the rumors have been colored by the fact that Lavinia’s sister was pregnant, and that the Strattons might have been seen in the vicinity of a newborn boy? I still hold that Lavinia probably could not have carried a child to term. If it was anything like her or Charles, it would have been a fairly large baby and complications would easily have arisen. That was exactly how her sister Minnie later died. The official narrative was that Lavinia gave birth to a three-pound girl. Improbable, but Minnie Warren seems to have bought into the idea. Lavinia was also touring during the time a Stratton baby would have been born. It makes sense for the baby to be a fraud, although that makes the grave mysterious. But the later account of the fraud is just as confusing and doesn't match up with the timeline shown by newspapers. A big part of the hoax is the photos that are left. These would have been sold as souvenirs. I’ve been collecting all the photos I can of the Stratton family, and there are two groups in particular that seem to have been taken in long photo sessions at different periods in time. You can identify two studios, with common set pieces. The clothes – particularly Lavinia’s gowns – are also clear markers. As for the baby, there are clear differences between the two groups of photos, BUT it is hard to say whether we are looking at two different children, or one child at different stages of development. There is no obvious “OMG that’s a completely different kid!!!” There’s no huge difference in facial structure. In the first group of photos, attributed to the famous Civil War photographer Mathew Brady, the baby lies cradled in Lavinia’s arms, wearing a long christening-syle gown as she gazes directly at the camera. (A photo where she is smiling - here - is the most-reproduced picture of the trio). Her long wisps of hair are visible in several copies, and in one colorized photo have been painted bright yellow. The image at the top of this post has several pictures of the Mathew Brady baby. In the second group of photos, which I believe were taken by the London Stereoscopic and Photographic Company, the baby now sits unsupported, and is much more active (typically seen with face slightly blurred in movement, often looking away from the camera). Her hair looks like it is parted in the middle and smoothed back. She wears dresses with wide skirts. Her size relative to the Strattons does seem roughly the same as before, but it’s hard to tell due to the long gown used in the previous photos. You can see one such photo in this post. You can find more photos with a simple Google search. What do you think? Are there different babies in the different photos? What was going on with Lavinia's mysteriously inconsistent interview? And who is the child buried in Minnie Stratton's grave? The Three Little Pigs is one of the most iconic fairytales, instantly recognizable in any list. But where did it come from? In fact, the earliest known version of the story actually features not pigs, but pixies.

This story, Aarne-Thompson-Uther Type 124, resembles tales like "The Wolf and the Seven Young Kids" (ATU 123) and "Little Red Riding Hood" (ATU 333) where a predator tries to gain access to its prey's home through trickery or force. The listener identifies with a child like Red Riding Hood, or a domesticated animal like the goats or pigs. Sometimes the victim escapes with a clever trick. In other versions, he or she is gobbled up whole, and may or may not escape the wolf's belly. However, the three pigs are sort of latecomers. In 1853, an untitled story about a fox stalking a group of pixies was published in English forests and forest trees, historical, legendary, and descriptive. The story was also recorded in “The Folk-Lore of Devonshire” in Fraser's Magazine vol. 8 (1873). The pixies in the fox story live in an oddly domestic colony; two who dwell in wooden and stone houses are eaten. The fox, in search of prey, knocks at each door and calls "Let me in, let me in" before breaking the house open. However, a clever third pixie lives in an iron house which the fox can't break into. At the end, the fox finally captures the pixy in a box. However, the pixy uses a magical charm to trick him into switching places, and the fox dies. This is the earliest known version of the story. So how did we get to pigs? [Edit 3/23/21: J. F. Campbell's Popular Tales of the West Highlands, first published around 1860, mentions the pig story. "There is a long and tragic story which has been current amongst at least three generations of my own family regarding a lot of little pigs who had a wise mother, who told them where they were to build their houses, and how, so as to avoid the fox. Some of the little pigs would not follow their mother's counsel, and built houses of leaves, and the fox got in and said, "I will gallop, and I'll trample, and I'll knock down your house," and he ate the foolish, little, proud pigs; but the youngest was a wise little pig, and, after many adventures, she put an end to the wicked fox when she was almost vanquished, bidding him look into the caldron to see if the dinner was ready, and then tilting him in headforemost."] In 1877, Lippincott's Monthly Magazine featured William Owens' article "Folk-Lore of the Southern Negroes," including the story of "Tiny Pig." Seven pigs are hunted by a fox, who goes to each of their houses and asks entrance. The pigs each reply in rhyme, "No, no, Mr. Fox, by the beard on my chin! You may say what you will, but I'll not let you in." The fox proceeds to blow down each house and eat the occupant. Only the seventh one, Tiny Pig, has built a strong stone house, and the fox finds that he cannot blow it or tear it down. The fox attempts to enter through the chimney, but Tiny Pig has a fire waiting for him. In an odd note, Owens compares "Tiny Pig" to an Anglo-Saxon tale called "The Three Blue Pigs." He implies that this was the source for the African-American tale. He gives no source for this story, but it seems he expected his readers to recognize it. However, Thomas Frederick Crane, a collector of Italian tales, seemed baffled by the reference and wrote that he was unable to find the tale. The tale seems to have been strongly present in African-American folklore of the time. In addition to this appearance in Lippincott's Magazine, Nights with Uncle Remus: Myths and Legends of the Old Plantation by Joel Chandler Harris (1883) featured "The Story of the Pigs." Five build houses for themselves from "bresh," sticks, mud, planks, and rock. Brer Wolf sweet-talks and lures each one, coaxing them to open the doors of their respective homes. In this way, he devours them one by one. Only the Runt sees through his deception. In a scene reminiscent of both Red Riding Hood's dialogue with a disguised wolf, and the Seven Kids' protests that the wolf doesn't resemble their mother, Runt sees through each of Brer Wolf's claims that he's one of her siblings. Again, there is the ending with the chimney and the pig's waiting fire. A Harris story published later, "The Awful Fate of Mr. Wolf," told a similar narrative with Brer Rabbit as the protagonist. "The Three Goslings" appeared in Thomas Frederick Crane's Italian Popular Tales in 1885. This is another close variation on the story, but with geese rather than pigs. Here we find the wolf blowing down houses. Ultimately, the third gosling pours boiling water into the wolf's mouth to kill him, and then cuts open his stomach to free her sisters. (I'm not sure why the boiling water didn't hurt them.) Crane collected this from Tradizioni popolari veneziane raccolte by Dom. Giuseppe Bernoni, vol. 3 (c. 1875-77). He also included a story called "The Cock," which similarly featured a wolf blowing down animals' houses (in this case built of feathers). Our modern famous trio of pigs can be traced back to James Orchard Halliwell's Nursery Rhymes of England (1886). The tale was titled "The Story of the Three Little Pigs." Here is the final pig living in a brick house. Here are the rhyming couplets with the wolf calling out, "Little pig, little pig, let me come in" and huffing and puffing houses in. A few scenes, such as the wolf trying to lure out the pig and the pig duping him, are identical to scenes in the pixie story. As in the Italian stories, the wolf blows down the houses, and as in the African-American versions, the ending has the wolf's descent through the chimney. (However, the pig boils him and eats him, reminding one of the Italian gosling's boiling pot of water.) The British version featuring the pigs gained popularity through Joseph Jacobs' English Fairy Tales (1890), which cited Halliwell. Another version showed up in Andrew Lang's Green Fairy Book (1906). Some African and Middle-Eastern versions tell the same story with different animals, such as sheep or goats. In some areas, human main characters seem more popular, as in the Moroccan tale of Nciç (Scellés-Millie, Paraboles et contes d’Afrique du Nord, 1982). A sultan and his seven sons travel to Mecca, but one by one the sons lose courage and build houses - one with walls of honey, another with walls of date paste. The seventh and smallest son Nciç builds an iron house and faces off against a ghoul. The story of the fox and the pixies remains an outlier. It is the first known tale to introduce the now-familiar framework of the Three Little Pigs. However, it is also oddly rare. Pigs, fowl, goats, and humans all star in similar tales, but I've never encountered another version with pixies. And what exactly makes foxes a natural enemy of pixies? The 1873 article in Fraser's Magazine remarks that "There is a very curious connection between the pixies and the wild animals of the moor, especially with the fox, which features in many local stories. These turn frequently on a struggle in craft and cunning between the fox and the pixie." However, the only story cited is this one - not exactly a large sample size - and the author admits that the story of the pixies living in individual houses of iron, etc., is atypical. Meanwhile, in the other stories recorded in English Forests, pixies are "merry wicked sprites" who torment horses, lead humans astray in the woods, and steal babies. These are not cute winged fairies. They appear as "large bundles of rags," or occasionally tiny sprites dressed in filthy rags. Rather than being harmed by iron like some folkloric fae, they are miners and metalworkers. In one story, they are apparently immune to gunfire ("they were not to be harmed by weapon of 'middle earth'"). In the fox story, however, they are hapless creatures easily devoured by a woodland animal. The only pixy-ish thing they do is at the very end, when the final survivor uses an unspecified "charm" to entrap the fox. I believe the answer is lies in a confusion between similar words. The word "pixy" is close to "pig" - and that's before you get into related words like puck or pug. One variation is pigsies or pigseys. Pigsie is a Devonshire term for pixie. The story of the fox and the pixies is from Dartmoor, in Devon. The pixie version could have arisen through a misinterpretation of the animal pig (or piggie) as the supernatural creature pigsie. If it was originally about pigs, that would explain why similar tales frequently feature animal heroes, and the same tale was widespread with pig protagonists even on the other side of an ocean. It would also explain why the Dartmoor tale's pixies act so unpixylike and helpless, with only one mention of magic thrown in at the end almost as an afterthought. I can only think of a couple of versions of The Three Little Pigs which feature fairies as protagonists, and they are modern take-offs. In 1996, a book titled Feminist Fairy Tales by Barbara Walker featured a parody of the Three Little Pigs as "The Three Little Pinks." In this fable about girl power, a misogynistic gardener named Wolf comes at odds with three flower fairies who share the task of painting flowers pink. I found this parody less than impressive. But it's still intriguing in how it cycles - perhaps unknowingly - back to one of the earliest published versions of the tale. Oh, and there was an early 20th century version of "The Wolf and the Seven Young Kids" which featured a goblin and seven little breeze spirits. That was "The Gradual Fairy" by Alice Brown, published in 1911. I do wonder about the "Three Blue Pigs" tale mentioned by William Owens, which could potentially date back before the tale of the fox and the pixies. Perhaps it didn't survive. That would be a fascinating find, though. SOURCES

There's a popular conception that fairytales all take place a very long time ago, in ancient times with princesses and castles and knights. That's partly true. But then why are there no "modern" fairytales?

I believe most people who told oral folktales, while they may have featured princesses and castles and so on, pictured the events as happening in towns like their own, with technology like their own. Contemporary settings. Folktale collecting's major boom began around the early 1800s with the Brothers Grimm. We also had a wave of fairytale writers, like Hans Christian Andersen, inspired by folktales. The result of the folklore movement was fairytales frozen in time. Now that they were in print, they existed as the product of that time period. Just for context, the telegraph was invented in 1837. The first telephone was 1876, the light bulb 1878. You had Napoleon, the Louisiana Purchase, the American Civil War (in no particular order). People living in the 1800s would have lived to see the first films and World War II. The image at the top of this post is an illustration of the Grimms' tale "The Four Skillful Brothers." It looks very fantastical and medieval, right? That looks like the kind of dragon you'd slay with a sword. Spoiler alert: someone shoots that dragon with a gun. Guns actually appear a lot of fairytales, from the Grimms and otherwise. You see the same thing in literary fairytales like Hans Christian Andersen's. In Andersen, there's a wide range. The Marsh King's Daughter features Vikings, but The Steadfast Tin Soldier has tin soldiers, muskets, ballet, and plumbing. Today, there's a sort of "fairytale canon" in the popular mind, strongly influenced by Disney. Even Disney fairytales tend to be set in a vague, anachronistic past. For instance, Snow White is a mishmash of elements from different historical periods. Their clothing is medieval fantasy, but there's gas technology and a Bunsen burner in the Evil Queen's lair. The Bunsen burner was invented in the 1850s. Are there any modern fairytales set in modern times? It depends on what you mean. Although oral storytelling isn't as popular, we do have people continuing to retell and adapt fairytales as movies or as books. In many cases, these retellings are set in contemporary times. See Cinder Edna, a picture book by Ellen Jackson, where the main character takes a bus to the ball. There are also plenty of fantasy short stories which have modern flavors. Or even Internet folklore like Slenderman. But I do think that if you set out to collect oral folktales being told today, you will find fairytales set in worlds like those the storytellers inhabit. There are collections created well into the 20th century. Hasan el-Shamy has collected folktales from the Middle East. Another example is Barbara Rieti's Strange Terrain: The Fairy World in Newfoundland, published 1991. At one point in 1985, she attempted to track down the origins of a local tale of a little girl taken away by fairies. You would think of that as happening in a long-ago distant time - which Rieti initially did. But then she actually met the person involved, who was then in her sixties (and who did not seem happy at her experience being turned into a fairytale). She had been lost in the woods for over a week and suffered from hypothermia. This happened in the 1930s. I think there's a Disney-influenced imagining of fairytales as all taking place in the distant past, further influenced by a lack of context for just how recently these tales were set down in print. In 1697, Charles Perrault published the story of "Cendrillon: ou la Petite Pantoufle de verre" (Cinderella, or the Little Glass Slipper). This is probably the most widespread version of Cinderella, thanks in large part to its adaptation by Walt Disney. I often see people on the Internet insist that "the original Cinderella wore gold slippers and had the stepsisters cut off their toes and get their eyes pecked out by birds!" But that was "Aschenputtel," the version from the Brothers Grimm. Perrault published his work 115 years before the Grimms did. It's impossible to identify an "original" version of Cinderella, but at least in terms of publication, the glass slipper came first.

But was it really a glass slipper? There is a persistent theory that the shoes were originally made of fur - which is about as far from glass as you can get! This theory may have originated with Honore de Balzac, in La Comédie humaine: Sur Catherine de Médicis, published between 1830 and 1842 and finalized in 1846. The word for glass, "verre," sounds the same as "vair" or squirrel fur. This fur was a luxury item which only the upper class was allowed to wear. Therefore, claimed Balzac, Cinderella's slipper was "no doubt" made of fur. Since then, quite a few authors have relied on this alternate origin for Cinderella's origins, usually in order to fit the story into a more "realistic" mold. It has also produced a persistent legend in the English-speaking world that Perrault used fur slippers and was mistranslated. Yes, glass shoes raise questions. How did she dance in them? How did she run in them? Wouldn't they have shattered? Wouldn't they have been super noisy? Fur slippers erase those questions entirely. But Cinderella stories regularly include things like dresses made of sunlight, moonlight and starlight. Forests grow of silver, gold and diamonds. Prisoners are confined atop glass mountains. In Perrault's version alone, mice are transformed into horses and pumpkins into carriages. Glass slippers should not be an issue. In fact, they fit perfectly well with the internal logic of the fairytale. As has been pointed out by others, the whole point of the slippers is that only Cinderella can wear them. Fur slippers are soft and yielding. Glass slippers are rigid and you can see clearly whether they fit a certain foot. Moving into symbolism: they are expensive, delicate, unique, magical. Cinderella must be light and delicate, too, in order to dance in them. They are a contradiction in terms (of course it would be impossible for a woman to dance in glass shoes! That's the whole point!) and that's why they have captured so many imaginations. The fact is that Perrault wrote about "pantoufles de verre," glass slippers. He used those words multiple times. There is no question that he was talking about glass. No one mistranslated Perrault. However, did he misunderstand an oral tale which mentioned slippers of vair? It's important to note that "vair" was popular in the Middle Ages. By Perrault's time, this medieval word was long out of use! It is still possible that Perrault could have heard a version with vair slippers - but is it probable? What stories might Perrault have heard? In her extensive work on Cinderella, Marian Roalfe Cox found only six versions with glass shoes. She found many that were not described, many that were small or tiny, and many that were silver, silk, covered in jewels or pearls, or embroidered with gold. A Venetian story had diamond shoes, and an Irish tale had blue glass shoes. Cox believed that other versions with glass slippers were based on Perrault's Cendrillon. Paul Delarue, on the other hand, thought these versions were too far away in origin, which would make them independent sources - which means Perrault could have drawn on an older tradition of Cinderella in glass shoes. Gold shoes are perhaps significant. Ye Xian or Yeh-hsien, a Chinese tale, was first published about 850, and its heroine's shoes are gold. Centuries later, the Grimms' Aschenputtel takes off her heavy wooden clogs to wear slippers “embroidered with silk and silver,” but her final slippers - the ones which identify her - are simply “pure gold.” It’s not clear whether this means gold fabric or solid metal. As for other early Cinderellas: Madame D'Aulnoy published her story "Finette Cendron" (Cunning Cinders) in 1697, the same year as Perrault's Cendrillon. Her heroine wears red velvet slippers braided with pearls. Realistic enough. The Pentamerone (1634) has "La Gatta Cenerenterola" (Cat Cinderella). It's not said what the heroine's shoes are made of, but she does ride in a golden coach. Note that shoes are not always the object that identifies the heroine. In many tales, it's a ring - something likely to be made of gold or studded with gems. What if, at some pivotal point, far back in history, a storyteller combined the tiny shoe and the golden ring into a single object? On the other hand, I have never found a Cinderella who wears fur slippers to a ball. Fur clothing appears in Cinderella stories such as "All-Kinds-of-Fur," but it's used as a hideous disguise. Rebecca-Anne do Rozario points out that "Finette Cendron" (which, again, came out the same year as Perrault's "Cendrillon") has Finette instruct an ogress to cast off her unfashionable bear-pelts. Fur clothing was not a symbol of wealth or status, but of wildness and ugliness. Glass slippers were most likely Perrault's own invention dating from when he retold his folktales in literary format. No translation error, no misheard "vair" - just a really good idea and his own storytelling touch. If anything, he probably heard stories where the slippers were made of gold, or where their material was not mentioned. It was only later writers like Honore de Balzac who added the confusion of the squirrel-fur slippers, and folklorists and linguists have been arguing against it ever since. James Planché wrote in 1858, "I thank the stars that I have not been able to discover any foundation for this alarming report." That was twelve years after Balzac's book was officially completed. Heidi Anne Heiner at SurLaLune points out that the vair slipper theory dismisses Perrault's "adept literacy," and "negates [his] interest in the fantastic and magical, discounting his brilliant creativity." Unfortunately, as shown by Alan Dundes, the vair/verre theory made it into influential sources such as the Encyclopaedia Britannica, and thus has been fed as fact to successive generations of readers. Who's going to question the Encyclopaedia Britannica? And so this rumor remains persistent. As a final bit of trivia: there is one mention of glass shoes in the Brothers Grimm's tales. “Okerlo” appeared only in their 1812 manuscript and was quickly removed. (This is perhaps because it is clearly a retelling of a French literary tale, “The Bee and the Orange Tree.” Not unusual for the Grimms, but in this case it may have been just too blatant.) In the final lines, the narrator is asked what they wore to a wedding. They describe ridiculous clothes, with hair made of butter that melts, a dress of cobwebs that tears, and finally: “My slippers were made of glass, and as I stepped on a stone, they broke in two.” Here, the destruction of the fairytale clothing points out how impossible the magical tale is, and signals the end of the story and a return to reality. Sources

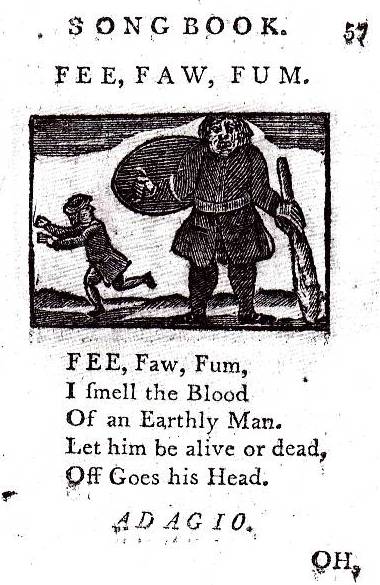

This incomprehensible phrase is most famous for appearing in "Jack the Giant Killer." Most versions adhere to basically the same model:

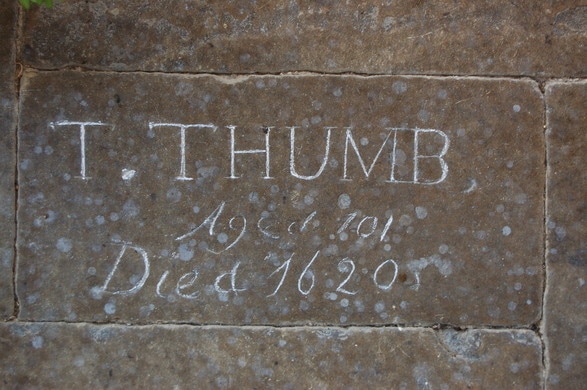

Fee-fi-fo-fum I smell the blood of an Englishman. Be he alive or be he dead I'll grind his bones to make my bread. What does "fee-fi-fo-fum" actually mean? Nobody knows. Although there have been theories. (Does fie mean a cry of disapproval, as in "Fie! Fie!"? Or does it come from the Gaelic word for "tasty"? I'm leaning towards "neither, just a nonsense phrase.") When Thomas Nashe mentioned it in Have with you to Saffron-walden (1596), it was already an old saying of obscure origin. "O, tis a precious apothegmatical Pedant, who will find matter enough to dilate a whole day of the first invention of Fy, fa, fum, I smell the blood of an English-man". (I have to say, I love that paragraph.) It also appears in King Lear (1605): Child Roland to the dark tower came, His word was still, Fie, foh, and fum, I smell the blood of a British man. In 1814, Robert Jamieson's version of Childe Rowland in Illustrations of Northern Antiquities had the Elf-king proclaim, "With fi, fi, fo, and fum! I smell the blood of a Christian man! Be he dead, be he living, wi' my brand I'll clash his harns frae his harn-pan! " [I'll dash his brains from his brain-pan] And in Tom Thumb (1621) - on this blog you know it's always going to come back to Tom Thumb - the hero encounters a giant who says, Now fi, fee, fau, fan, I feele smell of a dangerous man, Be he alive, or be he dead, He grind his bones to make me bread. So, by 1621, the rhyme was already associated with giants, and the colorfully gruesome idea of bone-meal bread was in existence. (Tom Thumb, as well as being the first fairytale printed in English, has lots of common fairy tale tropes, such as the fairy godmother.) So the phrase fee-fi-fo-fum has been around a long time. It first appeared in print in combination with Jack the Giant Killer when that story was printed in 1711. Regarding Childe Rowland, Jamieson recalled hearing a version in his childhood from a tailor: "the tailor curled up his nose, and sniffed all about, to imitate the action which "fi, fi, fo, fum!" is intended to represent." So maybe "fee fi fo fum" is meant to be some kind of onomatopoeia for smelling? I don't know how that would work, but I do find the different variations interesting. It looks like it was once more common to have only three syllables instead of four. Although this phrase is English, there are parallels to monsters detecting people by the smell of their blood in other countries. In Perrault's Popular Tales, Andrew Lang connects this theme to the Furies in Aseschylus' Eumenides. Most editions of the Tom Thumb fairytale end with the king erecting a monument in memory of the pint-sized hero. Here lies Tom Thumb, King Arthur's knight, Who died by a spider's cruel bite. He was well known in Arthur's court, Where he afforded gallant sport; He rode a tilt and tournament, And on a mouse a-hunting went. Alive he filled the court with mirth; His death to sorrow soon gave birth. Wipe, wipe your eyes, and shake your head And cry,--Alas! Tom Thumb is dead! In fact, there is a real tomb for Tom Thumb. There was once a blue flagstone serving as his tombstone at the Lincoln Cathedral. According to a 1819 edition of the Quarterly review, the tradition was that Tom Thumb died at Lincoln, and "the country folks never failed to marvel at [the blue flagstone] when they came to church on the Assize Sunday; but during some of the modern repairs which have been inflicted on that venerable building, the flag-stone was displaced and lost, to the great discomfiture of the holiday visitants." (The Quarterly Review, 1819, p101). Here is more on the renovations, although it has no mention of the flagstone. What we do still have is a tombstone and a house for Tom Thumb, roughly twenty miles away, in Tattershall, Lincolnshire. "T. Thumb, Aged 101, Died 1620." Is there really someone buried under this marker? Could he be connected to the fairytale? The tombstone is located in the Holy Trinity Collegiate Church and can be found in the floor, near the font. The website of an affiliated church group notes that this Tom Thumb was "47 cm tall" or about 18.5 inches. An Atlas Obscura article cites rumors that he frequently visited London and was a favorite of the King. The date of 1620 is intriguing, because it puts this local legend of Tom Thumb right about the same time we have our first surviving textual mentions of the name - the grave is marked 1620, and the earliest known printing of Tom Thumb was in 1621. (See the Tom Thumb Timeline.) The grave is usually seen decorated with flowers and a poem. Here is an excellent shot from the Atlas Obscura article. Elizabeth Ashworth's blog has another photo, with a closer look at the poem, as well as more history on the church. The poem, by Celia Wilson, doesn't have much information besides this is Tom Thumb's grave, he'd probably have a lot of stories to tell. Then there is Tom Thumb's house, not far away. Most articles on the grave mention it as if it is the actual home of the buried T. Thumb. However, further research shows that it's not a house that anyone ever lived in. It's a decoration. It is located on the ridge of Lodge House, in the Marketplace. The Lodge House is itself a building of historical interest. According to Historic England; "On the roof ridge is a ceramic [14th century] louvre in the form of a gabled house, known as 'Tom Thumb's House'." On medieval buildings, a louvre or louver was a kind of turret or domed structure on the roof, which allowed in air and light but not rain. The Tattershall and Tattershall Thorpe Village Site, available through Wayback, informs us that "The tiny house was thought to keep evil spirits out of the main building. Tom Thumbs house changed from one side of the Market Place when Mr Wright sold his shop." Here's the Lodge House on Google Maps. Can you see Tom Thumb's house? Try looking at this photo from the Village Site. So: two traditions that Tom Thumb died somewhere around Lincoln. And one of them is dated around the same time as the first existing mentions of Tom Thumb.

If any of you readers go to Tattershall any time soon... you know what your homework is. There was a study around 2013 by anthropologist Jamie Tehrani, who concluded that "Little Red Riding Hood" and "The Wolf and the Kids" are two descendants of a common ancient ancestor.

This is an example of monogenesis. I've been reading a little about polygenesis and monogenesis, after someone mentioned them on a site I frequent. As it relates to folktales, polygenesis means the tale originated from many sources independently and spontaneously, and monogenesis means it originated from one source and was diffused. I think I can safely say that the German Daumesdick, the Russian Malchik-s-Palchik and the Italian Cecino are all the exact same story. This story appears frequently, under different names, across Europe, Asia, and North Africa. Further south in Africa and on other continents, it doesn't seem to show up at all until colonists brought it there. It's pretty clearly one story that was diffused around a specific landmass. Where it gets more interesting is examples like the English Tom Thumb and the Japanese Issun-Boshi. These tales are from opposite points of the Thumbling tale area, and were first published far before the others. They share a few points: the wish for a son miraculously granted, the tiny boy leaving home, wielding a needle as a sword, serving a nobleman, and being swallowed by a beast. In every other aspect, they differ completely. Issun-Boshi was probably first written down sometime during the Muromachi period (1392-1573), and there were other stories of tiny people, like the god Sukuna-biko, first described in the 8th century, or Princess Kaguya, first written down in the 10th century. There's evidence of a Tom Thumb tradition in England as early as 1579. Portuguese traders reached Japan in 1543, so there's contact between Europe and Asia at that point. Did these stories have the same source, or were they simply examples of a universal interest in tiny people? Did some country somewhere in the middle produce the proto-Thumbling tale? I was interested in the same stories appearing across different cultures long before I got onto this project. For instance, the story of a great flood as punishment from a deity (usually with only a handful of survivors in a boat) is universal. It's in the Middle East. It's in Europe. It's in Asia. It's in Africa. It's in the Americas. It's in Australia. Is this polygenesis or monogenesis? Is it just because all of these cultures had lived near water and seen catastrophic floods, and they wanted to tell stories about them, and the folktales emerged in a kind of convergent evolution? Or could these stories possibly serve as evidence for a singular Great Flood? Some proponents of polygenesis in folktales based it on a theory of psychic unity among humans, and the idea that all cultures went through exactly the same stages of development. The term "universal human psyche" tends to pop up in some of these sources. Proponents of monogenesis have also come up with some weird theories. There was a period of time where quite a few scholars posited that all stories were connected. If there was a similar name, it was the same person. In many cases, this was leaping to conclusions. For instance, not all characters named Thomas are the same person. Tom Thumb is not Tam Lin. I think, as time has passed, this particular theory has fallen out of favor. Overall, monogenesis and diffusion seem far more likely to me, although there are still cases for different groups coming up with the same idea. Like, say, a sky god who controls the thunder. FURTHER READING

Charles Stratton, more famous by his stage name General Tom Thumb, wed Lavinia Warren on on February 10, 1863. Both had a form of dwarfism and were among P. T. Barnum's most renowned performers. They toured the world and people gathered to marvel at their small size - Charles was 3'4" and Lavinia 2'8". They rode in a miniature carriage. They had miniature furniture. All they needed was a miniature baby. It was announced that their child was born on December 5, 1863. Most sources referred to it simply as a baby or child, and at least one periodical appeared to think it was a boy. The overwhelming evidence, however, points towards a baby girl who was named Minnie after her aunt. She went on tour with them and was mentioned by name as early as 1864 in English papers. There was some disagreement as to whether Minnie would take after her parents' "Lilliputian" stature, but she was undoubtedly a hit and always described as a very beautiful child. They sold a fortune's worth of pictures of the happy little family. Tragically, less than three years later, newspapers reported that "Minnie Tom Thumb" (her nickname) had died. She suffered from an inflammation of the brain while in Norwich, where her parents were touring ("Foreign News and Gossip." Brooklyn Eagle. Oct 15, 1866). She was mentioned in Charles' obituary in the New York Times, and in 1882, the Strattons' manager, Sylvester Bleeker, said the child had looked just like her Aunt Minnie. Then, in 1901, eighteen years after Charles' death, Lavinia told newspapers that she had never given birth at all.

Renting babies from orphanages? Abruptly announcing the child's death when the charade had run its course? It was exactly the type of thing people expected from Mr. P. T. "There's a sucker born every minute" Barnum. In fact, skeptics tended to preemptively declare Barnum's acts hoaxes; as soon as 1878, obituaries for Lavinia's sister mentioned "the spurious Thumb baby." And the Strattons had played along with Barnum - or even suggested it to him in the first place. Tom Thumb's baby was all a hoax. OR WAS IT? In the BBC documentary "The Real Tom Thumb," historian John Gannon claims that they really did have a daughter. He produces a death certificate and burial record for "Minnie Warren Stratton, daughter of the celebrated General Tom Thumb," a contemporary news article, and finally a tombstone in Earlham Cemetery in Norwich. The Norfolk News said that the private funeral was invaded by a crowd of about a thousand, and that the General planned to later have the body moved to America and reinterred (Norfolk News 29 September 1866 p.5). The reinternment never happened, and the grave still lies there today. Newspapers stated that the Strattons cancelled performances in order to grieve.

However, it has been accepted for over a hundred years that the child was a hoax. and John Gannon's records are far from conclusive evidence. Although it seems technically possible that Lavinia bore a daughter, the timeline makes it unlikely. She was performing onstage constantly during the year when the child would have to have been born. Pregnancy would also have presented her with the same risks that took the life of her sister, who was even smaller than she was, and who died in 1878 after a painful and difficult childbirth. The baby died with her. It left a deep mark both on her family and on the public. Even years later, in 1892, an article on the wedding of Admiral and Mrs. Dot (another small pair of performers) said, “Every mother in the room thought of Minnie Warren, and felt a throb of fear at the risk this little woman in white was taking.” On the other hand, the same article indicates rumors “that Tom Thumb’s son is nearly six feet high, and that he is very proud of his little mother.” There was no reason for Lavinia to say she'd faked a baby - willingly participating in such a hoax would not have made her look good. And it seems odd that, in her autobiography, she would mention the death of her sister (which affected her deeply) but not her daughter. As a matter of fact, her autobiography, which was probably written somewhere around 1900 or 1901, has no mention of a baby whatsoever. Because it was even more painful than her sister's death? Or because it had become an old shame? Later on, Lavinia's family went out of their way to set the record straight. Her nephew, Benjamin J. Bump mentioned the baby hoax in his 1953 pamphlet, "The Story that Never Grows Old," and in his correspondence with researcher Alice Curtis Desmond. His wife Edna wrote a letter to the editor of the New York Times on April 21, 1946, saying that "The Tom Thumbs never had a child." It seems most likely that the Strattons never had children, but they may have grown attached to their surrogates. Based on the death record and grave, it seems that one of these borrowed children died in their care, and they grieved for her and had her buried under the name Minnie Warren Stratton. That seems to have marked an end to the touring with babies. On the other hand, Bogdan in Picturing Disability dates one of the family photos to 1868, and Desmond reported in her 1954 book that they were exhibited with a baby in 1881 (page 215). On the other other hand, A. H. Saxon suggests that some European newspapers mistook Lavinia’s sister for a child (Autobiography). It was too long ago and there was too much misinformation to be sure. What gives me more pause is the 1901 interview with Lavinia. Although this article is frequently quoted, something seems off with the math, and the mention of the child apparently reaching age four before any problem was seen. Even though this was decades later, and memory can fade, how does the life and death of "Minnie Warren Stratton" mesh with the baby boy described in that article? SOURCES

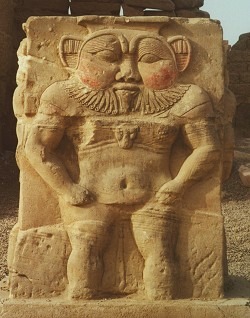

The dwarves of fairy tale and fantasy literature are characterized by their short stature and impressive beards. Tolkien defined the trope, and Disney undoubtedly helped by portraying six of Snow White's seven dwarves with full beards. In some stories, even female dwarfs are frequently supposed to have similar amounts of facial hair. Other little folk are similar, like garden gnomes with their white beards and leprechauns with red beards. Unlike the people of Europe who told stories of gnomes and leprechauns, Native American men rarely wore beards. However, in such countries there are stories of excessively hairy little people, like the Anishinaabe's Memegwesi, the Lakota's Wiwila Men (in some versions) or the Metis tale of the adventurous and womanizing "Little Man with Hair All Over" (a version of The Bear's Son, Type 650A). Tolkien based his dwarves on the dwarfs of Norse myth. However, Norse and Germanic dwarfs may not have originally been the short beings we immediately picture today. Still, the bearded dwarves we know today go back a long way. For instance, the ancient Egyptian god Bes had achrondroplasic proportions and was one of the few Egyptian deities depicted with a full set of facial hair. (James Romano theorizes that Bes is visually descended from a lion, which would explain his sometimes manelike 'do.)  Through export, Bes would become a popular deity with other peoples such as the Phoenicians and the Cypriots. In the 5th century BC, Ctesias described Indian pygmies two cubits tall, who raised livestock that was similarly small, and had a war going on with some cranes. These pygmies had grew their hair out to their knees and their beards past their feet, so long that they did not require any other clothing. There may have been seeds of truth in this story. Dwarfs in Arthurian romances were frequently described with beards, and in folklore throughout Europe, dwarves were described and drawn as little old men with long beards. Other examples:

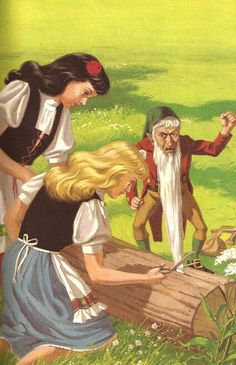

So why do dwarves have beards? Facial hair makes it immediately clear that despite his small size, the dwarf is not a child but a miniature adult. Such illustrations leave no room for confusion. (Fairies, who are not typically shown with beards, are usually more childlike and/or feminine.) From there, the exaggeration takes over. Sometimes the beard's length becomes purely silly and imaginative, as in stories where the tiny man's beard is longer than he is and trails on the ground like a parody of Rapunzel's hair. Some readers - from Jane Yolen on Rumpelstiltskin, to numerous critics of Tolkien's gold-loving dwarves - have suggested that these bearded dwarves are anti-Semitic caricatures. Jews in the Middle Ages were frequently depicted wtih beards. However, the trope of the bearded dwarf is so widespread and so old that it seems unlikely that they were all based on Jews. I think it's more likely that they were based on real people with achondroplasia, or real pygmy tribes. I feel like I should also mention that there was a story published by the Grimms called "The Jew in the Thorns," which featured both a bearded, thieving Jewish man and a supernatural-type dwarf who helped the hero get revenge on him. The beard is a symbol of wisdom and age. According to SurLaLune, a beard can also symbolize magical powers or invulnerability, or a sign of a somehow animal nature. The hairy little people of many Native American lores could have been influenced by Europeans coming over, but hair can still be a mark of physical maturity, as well as, again, a sign that the being is more like an animal than a human. In Snow White and Rose Red, the dwarf's beard is the source of his power. He catches it in a crevice in a tree and in a fishing line, and the girls cut it off to free him, taking his powers away in the process. Along the same lines, in the Pomeranian "Das Wolfskind," an ugly little man with a long black beard is poisoning people's food. The hero, Johann, traps the dwarf's beard in a split block of wood, and later hangs him by the beard from the ceiling and treats him like a tetherball (Jahn). This is type 650A. Here we see the beard as a physical manifestation of power. When someone else gains control of it, he is quickly left emasculated and powerless. There is definitely room for some Freudian reading here. Ultimately, my instinct is that the simplest explanation is the best: dwarves were drawn with beards so that nobody would mistake them for children. Egyptian art of Bes, for instance, sometimes had childlike attributes (such as going naked or wearing a lock of hair on the right side of his head). He could have easily been mistaken for a child had he not been drawn with facial hair (Åkerblom 15). And it just went from there, until beards were a defining characteristic of fairytale dwarves. SOURCES

|

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed