|

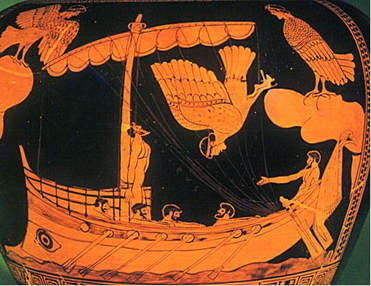

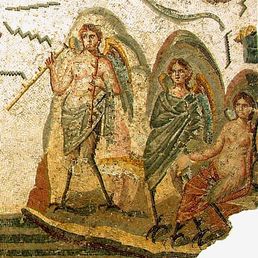

Sirens are not the same as mermaids. Mermaids are half-fish women, but sirens (the ones with the hypnotic singing voices) are half-bird women from Greek mythology. On the other hand, sirens and mermaids have been conflated for a long time. When did it begin? Sirens first appear in Homer's Odyssey in the 8th century B.C. Homer doesn’t really describe them at all. All we know is that their song will ensnare anyone who hears it. Later writers specify that sirens possess wings, or that they have the heads of beautiful women and bodies of birds. They may have drawn on Near Eastern myth-creatures like the ba of Egyptian cosmology. Human-faced birds were closely associated with the otherworld. Sirens mourned the dead in funerary art, and they were connected to Persephone, queen of the Underworld. Homer may have felt no need to describe sirens, since his audience would have known the context. Despoina Tsiafakis, however, suggests that the sirens could have gained avian attributes after Homer, when others sought to illustrate his work. (Tsiafakis p. 74) Meanwhile, fish-tailed people were a subject of art for a long time. They showed up in Mesopotamian art at least from the Old Babylonian Period (c. 1830 BC – c. 1531 BC). These were usually men, like the god Ea, but fish-tailed women sometimes appeared. Then in medieval times, sirens stopped being bird-ladies and became fish-ladies. But birds and fish aren't typically interchangeable. What happened? Even in Ancient Greece, sirens were already evolving. Male sirens used to appear in art, but disappeared as artists' attitudes shifted (Tsiafakis). Now all female and anthropomorphized, sirens changed from monstrous birds with human heads to instrument-playing women who happened to have wings and bird feet. The emphasis moved to their beauty and allure. In some late Greek art they appeared as women with no avian attributes at all (Harrison 1882). As the legend traveled abroad, things got even more complicated. In his Commentary on Isaiah (c. 404-410 AD), Jerome uses siren as a translation for a couple of words. Regarding thennim (tannim, or jackals) he adds, "Moreover, sirens are called thennim (תנים), which we interpret as either demons, or some kind of monsters, or indeed great dragons, who are crested and fly." So now, apparently, sirens are dragons. This sets the stage for the next stage of sirens, where they are symbols of evil and temptation. In his Etymologies, compiled between c. 615 and the 630s, Isidore of Seville seems split on the issue. He tells us of "three Sirens who were part maidens, part birds, having wings and talons.” But he goes on to explain that “in Arabia there are snakes with wings, called sirens (sirena).” In the Liber monstrorum (Book of Monsters), from the late 7th-early 8th century, the anonymous author proposes "a little picture of a sea-girl or siren, which if it has a head of reason is followed by all kinds of shaggy and scaly tales.” Then there’s the Physiologus, a bestiary which originated as a 2nd-century Greek text. As pointed out by Wilfred P. Mustard, the original Physiologus doesn't mention sirens. However, translations varied widely and contradictions were rampant. In a 9th-century copy from Bern, even though the text described sirens as avian beings, a confused illustrator added an illustration of a half-serpent woman. (Dorofeeva 2014) A early 12th-century German edition gives Sirene as "meremanniu," and a Middle English translation "mereman." (Pakis 2010) Despite the discrepancies between editions, the Physiologus was a universally popular source for creators of medieval bestiaries. People later in this list, like Bartholomaeus and Geoffrey Chaucer, mentioned it by name when describing their siren-mermaids. Some authors seesawed on the subject. Guillame le Clerc, in his Bestiaire (c. 1210) said that the beautiful, murderous siren has the lower body of "a fish or a bird." Bartholomaeus Anglicus, in De proprietatibus rerum, “On the Properties of Things” (1240), was careful to cover all his bases. "The Mermayden, hyghte Sirena, is a see beaste wonderly shape," he said, and proceeded to describe fish-women, fowl-women, crested serpents, and pretty much everything in between. In quite a few illustrations, "transitional" sirens held sway. In the Northumberland Bestiary (c.1250-60), sirens are a kind of human-bird-fish hybrid with amphibious webbed feet. Or take this illustration, where the siren is a winged merperson. By the 14th century, the siren's identity had become standardized as a fish-tailed temptress with a hypnotic voice. The words siren and mermaid were interchangeable.

When Geoffrey Chaucer translated Boethius' Consolation of Philosophy, (1378-1381) he translated sirenae as meremaydenes. Then, in Nonne Preestes Tale (1387-1400), he described a "Song merier than the mermayde in the see." Male Regle (The Male Regimen) by Thomas Hoccleve (1406) "...spekth of meermaides in the see, How þat so inly mirie syngith shee that the shipman therwith fallith asleepe, And by hir aftir deuoured is he. From al swich song is good men hem to keepe." In Edmund Spenser's Faerie Queene book II (1590s), "mermayds . . . making false melodies" tempt the heroes. These mermaids, Spenser explained, were once "fair ladies" but arrogantly challenged the "Heliconian maides" (the Greek Muses) and were turned to fish below the waist as punishment. (This sort of ties in with Pausanias’ Description of Greece from around the 2nd century A. D., where the Sirens and Muses had a singing competition. The Sirens lost and the Muses plucked out their feathers to make into crowns.) The original version of Sirens never fully went away. William Browne, in the Inner Temple Masque (1615) described Syrens "with their upper parts like women to the navell, and the rest like a hen." Still, sirens and mermaids remained generally synonymous, with few exceptions. English has the word mermaid for the fish-woman and siren for the mythological bird-woman. In Russian, too, the sirin has survived as a bird-woman. But in many other languages, “siren” is The Word for mermaid. According to Wilfred Mustard, "In French, Italian and Spanish literature, the Siren seems to have been always part fish." Languages that only use sirena or some variant for "mermaid" include Albanian, Basque, Bosnian, Croatian, French, Galician, Italian, Latvian, Polish, Portuguese, Romanian, Serbian, Slovenian, and Spanish. Aquatic mammals like manatees and dugongs belong to the order Sirenia. A congenital disorder that causes children to be born with fused legs is called Sirenomelia. Sirens have always been associated with the ocean and with sailors. They are the children of a river god. It makes sense that people would portray them as part-fish. But could the change have been intentional, at least on some parts? Jane Harrison suggests that “the tail of an evil sea monster” was meant to emphasize the siren’s corruption and darkness (p. 169). The book Sea Enchantress: The Tale of the Mermaid and her Kin proposes that the intention was to give the beautiful sea-maiden “a graceful fish-tail, since a bird-body is hardly seductive in appearance” (p. 48). Different lines of thought there, but the same effect. Whatever caused this evolution, it's clear that the modern mermaid is truly the direct descendant of the ancient Greek siren. SOURCES

Text copyright © Writing in Margins, All Rights Reserved

4 Comments

Becky

11/8/2021 11:32:20 pm

Who is the author? trying to cite this for an essay

Reply

Frank Gelli

4/6/2022 04:02:27 pm

The Italian writer Curzio Malaparte in his book 'The Skin' has a scene in which posh diners are served a siren on a dish. Everybody is shocked, takes it to be a little girl. Malaparte uses the word 'siren' throughout. The assumption is that a siren would have looked human enough to cause the shock. The creature in question is supposed to have come from the Naples Aquarium. Of course, no fish-like creature could be mistaken for a girl. Unless mythology had become reality!.

Reply

??

1/25/2023 10:12:38 pm

What?

Reply

Korben

3/6/2023 10:15:30 pm

this is amazing thank you

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed