|

The Little Mermaid isn't the only Danish tale about mermaids. I first discovered the tale of "Hans the Mermaid’s Son" in Andrew Lang’s Pink Fairy Book. Published 1897, this book gets sloppy with attributions. Some sources are given in detail, but other stories are simply labeled “From the Danish” or “From the Swedish.” A note in the foreword specifies that the Danish and Swedish tales were translated by MR. W. A. Craigie, but not where he got them.

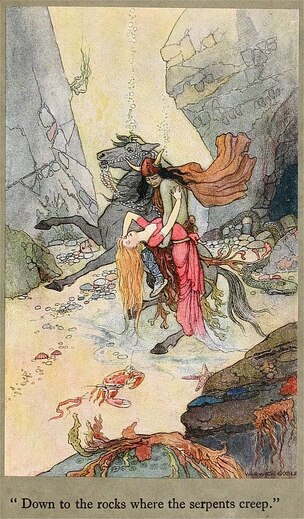

This made tracking down the story a real pain, but I finally worked out that the Danish tales are from Svend Grundtvig’s series Danske Folkeaeventyr (1876-1884). It's possible the editors thought "the Danish" was enough for readers to understand what they meant. This is Aarne-Thompson Type 650A, the Strong Boy. Way back in 2016, I analyzed a different version of this tale – “The Young Giant,” from the Brothers Grimm. The story is a comical tale of a super-strong laborer, who performs Herculean feats and makes fools out of his bosses and coworkers. It still strikes me as a gloomy tale when you think about the internal journey of the main character – from a tiny boy who just wants to help his father on the farm, to a strapping giant whose parents reject him out of fear, to a mean-spirited bully who uses his strength to hurt or humiliate others. So how does Hans the Mermaid’s Son measure up? Hans Havfruesøn was published in Danske Folkeæventyr volume II. Aside from Lang's translation, it appeared in German in 1878 as "Hans Meernixensohn," and in Gustav Hein's 1914 translation, it showed up as "Olaf the Mermaid's Son." The story begins by introducing a man named Rasmus Madsen. Rasmus is a common Scandinavian men’s name, short for Erasmus, and Madsen is a common Danish surname. At least, that's what it was in the version I found online. In the German, it is “Rasmus Matzen.” In Hein’s version, it is “Rasmus Natzen.” And in the Andrew Lang version, it’s simply “Basmus" (sic). Rasmus lives in a town called Furreby, by the strait called the Skagerrak. (Lang cuts this description, but oddly still mentions Furreby at the end of the tale.) Rasmus, a smith, struggles to earn enough to feed his wife and small children. He makes some money on the side by fishing. He goes out alone on a fishing expedition, but vanishes for several days and then turns up again mysteriously. What no one knows is that he was caught by a mermaid and spent several days with her. Seven years later, a boy named Hans shows up and announces that he is the mermaid's son, here to visit his dad, Rasmus. He's six years old, but looks at least eighteen. Like many heroes of Type 650A, Hans comes into being in a mythical way. Other equivalents may be the son of a woman and a bear, or may hatch out of an egg. Hans does not seem visibly half-merman, and his amazing size and strength aren't obviously related to his origin. However, there is one later scene where he doesn't seem to mind doing battle beneath a lake - more on that later. Hans has a massive appetite. After an entire loaf of bread doesn't fill him up, he declares that he must set out, for he won't have enough to eat here, and asks for the smith to make him an iron staff. It takes several tries before the smith crafts an iron rod that Hans cannot break. Hans thanks him and sets out. He winds up at a farm, where he offers to do the work of twelve men if he will also be fed the same amount as twelve men. However, the next day, Hans sleeps late into the morning and the gentleman (his boss) has to wake him. The men are threshing, and Hans has six threshing-floors to complete all by himself. Hans immediately smashes his flails by accident, so he makes his own flail so large that he must take the barn's roof off in order to use it. He threshes all of his work, but mixes up the different types of grain in the process. When told he must clean it up, he blows on the grain to filter all the chaff out. After another meal, Hans then sleeps the rest of the afternoon. The gentleman, meanwhile, is not too pleased with Hans, and makes a plan with his wife and the steward. The next day, they send all the men to the forest for firewood with a bet that the last one back will be hanged--they bet on Hans oversleeping, which he does. When he finally rises, the others have taken all the equipment, so he cobbles together a makeshift cart and gets two old horses to draw it. He accidentally breaks the gate on his way out, so replaces it with a huge boulder seven ells across (fourteen feet or so). When he catches up with the other workers, they laugh at him, since they already have carts loaded and ready with trees. Hans begins cutting down trees, but immediately breaks his axe, so he begins tearing up trees by the roots. The other workers stand staring openmouthed until they realize it's time to get going, and hurry back. Hans, meanwhile, finds that his weak old horses can't move the cart. "He was annoyed with this," so naturally carries the cart and all the trees on his back. The other workers, of course, cannot get past the boulder. "What!" Hans says, "Can twelve men not move that stone?" He throws the boulder out of the way, and arrives at the farm first. The gentleman sees him coming and bars the courtyard door in terror. When Hans knocks and doesn't hear an answer, he decides to throw the trees and the cart into the courtyard instead. The gentleman hurriedly opens the door before Hans can do the same with the horses. When the workers gather for their meal, Hans asks who's going to be hanged, and everyone hastily says it was just a joke. The gentleman, his wife and the farm's steward are now even more alarmed by Hans, and decide to send him to clean the well the next day, then drop stones on top of him. (This will also save them funeral expenses!) The workers are all in on this and drop heavy stones, but Hans calls up to them that gravel is landing on him. Finally they try the big millstone, but it lands on him like a collar instead. At this Hans comes out of the well complaining that the other workers are making fun of him, and shakes off the stone, which falls and crushes the gentleman's toe. The steward comes up with a final plan: sending Hans to fish by night in Djævlemose - which is a real place name. Lang renders it as "Devilmoss Lake"; Hein calls it "the devil's pool." There Hans will surely be captured by Gammel Erik, or Old Erik. This is a Norwegian folk-name for the Devil, equivalent to the English “Old Nick.” The Norwegian folklorists Asbjornsen and Moe collected a tale titled “Skipperen og Gamle-Erik,” or “The Skipper and Old Erik,” in which a sea-captain makes a bargain with the devil and outwits him. This story, like Hans Havfrueson's, is set on the water. Hans agrees to go fishing as long as he has a good meal, and rows out onto the lake. He decides to begin his snack before doing any fishing, but as he's eating, Old Erik drags him out of the boat and to the bottom of the lake. Hans happens to have his iron walking-stick, and beats Old Erik until the devil promises to bring all the lake's fish to the gentleman's courtyard. Hans then finishes his meal and goes home to bed. The next morning, the entire courtyard is filled with a mountain of fish. This time, the gentleman's wife suggests sending Hans to Hell to demand three years tribute, and tells her husband at random to send Hans south. (Lang changes this to Purgatory, presumably to censor it for children, even though it ruins the tale's theological consistency. Hein glosses it as "the infernal regions.") With a good supply of food, Hans sets out (and discovers that he has forgotten his butter-knife, but fortunately finds a plow to use instead). He meets a man riding by who says he's from Hell, and accompanies him. No one will let him in at the gate, so he smashes through it and beats up the demons who try to attack him. They run to Old Erik, who's still recovering in bed and who yells for them to give Hans whatever he wants. Hans returns to his master with a treasure trove of gold and silver coins, but is now "tired of living on shore among mortal men." He gives half of the treasure to the gentleman, takes the other half to his father, and then goes home to his mother. This tale strikes me oddly as softer than "The Young Giant." There is still the conflict between the uncontrollably strong youth and the complacent villagers who are all terrified of him and try to get rid of him by any means. The sequence of events is almost the same. Both heroes have legendary origins and go through parallel challenges. The iron walking stick and the millstone-around-the-neck scenes are near-identical. However, Hans doesn't seem to have the Young Giant's mean streak. Thumbling the Giant's masters fear him because he wants to beat them rather than getting paid in money. Hans' master also wants to get rid of him, but it's because Hans is unpredictable and unwittingly destructive. You can read Hans' dialogue as either clueless or slyly knowing - I'd lean towards clueless - but Thumbling speaks "coarsely and sarcastically." Hans blocks the way home with a boulder because he's accidentally broken the gate, but Thumbling stops and blocks the path purely to spite his coworkers. And though the gentleman and his wife plot multiple times to kill Hans, he leaves them with a massive pile of treasure. Thumbling kicks his boss into the sky, and kicks his wife after him even though she has done nothing that we know of. Overall, Hans feels like a more heroic character. When he gets into fights, it's with people who attack him first. Despite being lazy, gluttonous and oblivious, he seems good-natured (aside from not objecting to the idea that someone will get hanged for returning home last). Even with that, I do think it's relevant that he's really just six years old. Although both stories use the hero's physical strength for comedy, "Hans" leans harder on the parodic aspects (such as casually taking the roof off the barn to work, and Hans' meals getting progressively larger as the story goes on). There is still a sense of loneliness to a story where no one wants the hero around. However, I was better able to enjoy this version as a comedy. And with Hans disappearing into the boundless ocean at the end, it's possible to imagine him eventually finding a home where he fits in better, and maybe maturing a little. Sources

Other Blog Posts

1 Comment

Goldilocks and the Three Bears is one of the most famous fairytales today. It's also one of the most mysterious. Alan C. Elms wrote that Goldilocks "does not resemble any of the standard tale-types, and includes no indexed folktale motifs." For years, Goldilocks was believed to be a literary creation by a single author... until an older version surfaced in a library collection.

1831: Eleanor Mure wrote down "The Story of the Three Bears", (available here from the Toronto Public Library) in rhyme, with watercolor illustrations, as a birthday gift for her young nephew. She called it "the celebrated nursery tale," indicating that it was already famous, and she was just rendering it in verse. The story is different from the version familiar today. There is no Goldilocks. Rather, the story begins with three bears (all apparently male, referred to as the first, second and little bears) who move into a house in town. A snooping old woman, with no name, breaks into their house while they're out. Rather than porridge, she drinks their milk, but she breaks chairs and sleeps in beds just like the modern Goldilocks. Hearing the bears coming home, she hides in a closet. The bears return and discover the damage one by one. They find her, have difficulty burning or drowning her, and finally throw her on top of St. Paul's Church steeple. Mure's homemade manuscript remained unknown for years, until 1951, when it was finally rediscovered in the Toronto Public Library. Before that, the oldest known version had been Robert Southey's. 1837: Robert Southey anonymously published The Doctor, a collection of his essays. Among those was "The Story of the Three Bears." This is, in some ways, more like modern Goldilocks. The bears' meal is porridge. Again the antagonist is a nosy old lady. In a stroke of genius, Southey had the Great, Huge Bear, the Middle Bear, and the Little, Small, Wee Bear speak in appropriately sized type. The story ends with the old woman jumping out the window, never to be seen again. Southey described the story as one he had heard as a child from his uncle. Also, in letters from 1813, Southey mentioned telling the story to his relative's young children. 1849: Joseph Cundall made a significant change when he retold the tale in Treasury of Pleasure Books for Young Children. Namely, instead of an elderly crone, he made the antagonist a little girl named Silver-Hair. The "Story of the Three Bears" is a very old Nursery Tale, but it was never so well told as by the great poet Southey, whose version I have (with permission) given you, only I have made the intruder a little girl instead of an old woman. This I did because I found that the tale is better known with Silver-Hair, and because there are so many other stories of old women. However, Cundall might not have been the first person to do this; he implies that the tale is already "better known" as Silver-Hair. Both the name and the child character caught on very quickly, another possible indicator that he didn't make it up. The bachelor bears got a makeover, too. In 1852, illustrations were showing them as a nuclear family. And in 1859's The Three Bears. A Moral Tale, in Verse, the bears are identified as "a father, a mother, and child." 1865: An interesting aside here. In Our Mutual Friend, Charles Dickens titles a chapter "The Feast of the Three Hobgoblins." The characters eat bread and milk, and Dickens includes this line: It was, as Bella gaily said, like the supper provided for the three nursery hobgoblins at their house in the forest, without their thunderous low growlings of the alarming discovery, ‘Somebody’s been drinking my milk!’ As pointed out by Katharine Briggs, this could indicate another version of the story floating around. I think it should be noted that a synonym for hobgoblin is "bug-bear." Back to the evolving story of The Three Bears! The heroine’s name varied from Silver Hair, to Silver-locks, to Golden Hair, to Golden Locks - or, occasionally, she was nameless. "Golden Hair" appeared around 1868, in Aunt Friendly's Nursery Book. The variant "Goldilocks" soon gained popularity. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, this was a nickname for blonds as early as 1550. Old Nursery Stories and Rhymes (1904) is sometimes credited with the first use of the name Goldilocks for this story. However, Goldilocks was used for the Three Bears' antagonist as early as 1875 (Little Folks' Letters: Young Hearts and Old Heads, pg. 25, where the name is not capitalized). At this point, most people believed that the tale was created by Southey. In 1890, the folklorist Joseph Jacobs stated that the story was "the only example I know of where a tale that can be definitely traced to a specific author has become a folk-tale." However, Jacobs changed his opinion not long afterwards, when he received a story titled "Scrapefoot." This was collected by John Batten from a Mrs. H., who had heard it from her mother forty years previously. It appeared in Jacobs' More English Fairy Tales in 1894. This is close to the tale of Goldilocks that we know today, except that the main character who visits the castle of the three bears is neither a girl nor an old woman; it's a male fox named Scrapefoot. (There are quite a few parallels with Mure's version - the stolen food being milk, and the dilemma of how to kill the intruder.) Jacobs believed that Scrapefoot must be the older, more authentic version of the tale. He publicized the theory that Southey had heard a hypothetical third version with a female fox, or vixen, and had misinterpreted the word "vixen" to mean an unpleasant woman. However, Jacobs was building his theory based on the information he had at the time. He did not know of Mure's "Three Bears," which would not be discovered until 1951. We have two early, literary versions about an old lady, both of which state they heard the story from tradition - and one oral version, recorded later, about a male fox. Cundall's version, with Silver-Hair, is the oldest known to feature a child intruder. But Cundall possibly implies that other people were already telling versions with a young girl. And actually, there's more evidence for this - starting with Snow White and the Seven Dwarves. Goldilocks as a Motif In the Grimms' story of Snow White, first published in 1812, there is a long scene where the heroine - a young child in this version, seven years old - first finds the seven dwarfs' house. Inside the empty cottage she discovers a table set with seven places, and seven beds. Snow White eats a few bites from each plate and drinks a drop of wine from each cup. Then "She tried each of the seven little beds, one after the other, but none felt right until she came to the seventh one, and she lay down in it and fell asleep." When the dwarfs return, this happens: The first one said, "Who has been sitting in my chair?" The second one, "Who has been eating from my plate?" The third one, "Who has been eating my bread?" The fourth one, "Who has been eating my vegetables?" The fifth one, "Who has been sticking with my fork?" The sixth one, "Who has been cutting with my knife?" The seventh one, "Who has been drinking from my mug?" Then the first one said, "Who stepped on my bed?" The second one, "And someone has been lying in my bed." Eventually, they find Snow White lying there. Unlike the story of the Three Bears, however, the dwarves are so stricken with her beauty that they are happy to let her stay. Another fun fact: in the Grimms' original draft from 1810, Snow White is golden-haired. Her mother wishes for a child with black eyes, and in a later scene there's a reference to Snow White's "yellow hairs" being combed. The Grimms also published another story with a similar scene, "The Three Ravens." A girl sets out to rescue her three brothers, who were transformed into ravens. She travels through the harsh wilderness to the castle where they now live. There are three plates and three cups. The girl samples from each and drops her ring into the final cup. Just then, the ravens arrive; the girl might be hiding at this point, because the ravens don't seem to notice her. They each ask, "Who ate from my little plate? Who ate from my little cup?" But when the third raven looks into his cup, he finds the sister's ring, and the curse is broken. The Grimms edited the story significantly and changed it to "The Seven Ravens." However, I find it significant that the earlier published version had three talking animals. The stolen-meal scene also takes place briefly in "The Bewitched Brothers," a similar tale from Romania with two eagle-brothers. In other tales, the girl does not eat, but cleans the house and sets the table, then hides herself before her brothers come in. In a Norwegian variant called The Twelve Wild Ducks, the details are a little different, but the sister hides under the bed when her brothers arrive, and is discovered because she left her spoon on the table. In that version, at least one brother blames her for the curse, which explains why she might need to hide. In Journal of American Folklore, Mary I. Shamburger and Vera R. Lachmann argued that Southey pulled inspiration from Snow White and also from Norwegian lore. They say, "According to the Norwegian tale, the king's daughter comes to a cave inhabited by three bears (really Russian princes who cast off their bearskins at night). The king's daughter finds the interior of the cave very comfortable. Food and drink, especially porridge, are waiting on the table; she sees beds nearby, and after a good meal, she chooses the bed she prefers and lies not on, but underneath it!" They're describing "Riddaren i Bjødnahame" (The Knights in Bear-shapes). I would need someone more well-versed in Norwegian dialect to weigh in, but the details seem a bit different from the previous description. The bear-knights' home is not what I'd picture as a cave; it's a Barhytte, which is apparently a hut made of pine branches. I couldn't verify whether porridge is mentioned (if you know Norwegian landsmål, I would love to hear from you). The princess doesn't just move in and get comfy - she cooks the food and tidies up. The beds are a triple bunkbed (yes). And she doesn't take a nap - she is scared that the inhabitants may turn out to be dangerous, so she hides beneath the lowest bed. In fact, the Russian princes are charmed by her, and she ends up marrying one of them. Shamburger and Lachmann cited one other Norwegian tale in a footnote: "Jomfru Gyltrom." This is a parallel story, which does not feature the meal scene but does have three bear-princes. Incidentally, Jomfru Gyltrom's most notable characteristic is that she has a golden dove on her head. I don't think this is really connected to Goldilocks' name, but it's still an interesting parallel. The Three Bears today features a nuclear family with Mama, Papa and Baby Bear. However, in some of the earliest versions, all the bears are male. This is closer to the Snow White-eque tales, where the home is an all-male space. Sometimes it’s a cottage, sometimes a castle (as in Scrapefoot). The intruder is the only female. The male inhabitants may be animals, humans in animal form, or otherworldly creatures (such as dwarves, or… hmmm… Dickens’ hobgoblins?). The biggest difference is in the intruder's behavior. "Snow White" heroines are domestic goddesses who cook and clean wherever they go, but girls in "Three Bears" stories are forces of destruction. Conclusion: I talk about tale types, but honestly, a lot of tales don’t stick to identified types. They’re more a collection of motifs. The Norwegian stories mentioned are Snow White tales, but not exactly. Both contain the essential elements of Snow White, but also other stories – “The Knights in Bear-shapes” turns into an East o’ the Sun, West o’ the Moon-type tale after the heroine wakes up, and “Jomfru Gyltrom” has an extended ending where the heroine’s stepsister impersonates her. “The Three Ravens” ends with the heroine locating her brothers, but other stories of that tale type typically continue after that point, with the heroine sewing shirts to break the curse. In a different case: one obscure English folktale, Dathera Dad, is parallel to a single scene from Tom Thumb. The essential elements of Goldilocks are contained as a single scene in the stories of "Snow White" and "The Three Ravens," published in Germany in 1812, 19 years before Mure wrote down her version. In the 1810 version especially, Snow White was a seven-year-old blonde girl. Both Mure and Southey make reference to the story of the Three Bears being well-known. I wonder which came first. Was there a short story of a woman entering the animals' house and eating their food, which got absorbed into longer stories of a woman seeking shelter? Or did the Goldilocks scene break off from longer stories and take on a life of its own? I believe that Goldilocks is an older story than it's been given credit for; it seems as if people are constantly finding that certain details - like the name Goldilocks - are older than previously realized. And I think the similarities to Snow White are too notable to be ignored. It's just that Southey's literary version gained notoriety and became the most influential version very quickly, while stories such as Dickens' "Three Hobgoblins" may not have been recorded. And who knows - if Mure's version showed up more than a century after it was written, we might unearth other old versions. Mure's "Three Bears" up-ended all previous theories about Goldilocks. Joseph Jacobs thought Southey had misheard a story about a fox. Shamburger and Lachmann suggested that Southey had pulled his ideas from Norwegian folklore. But the discovery of this earlier version proved that Southey wasn't just making things up when he talked about hearing the story from his uncle; other people were already telling the story to their children. Sometimes, if a tale doesn't contain any indexed motifs, it's time to update the index. Sources

“Elphin Irving, the Fairies' Cupbearer” is a Scottish tale very similar to Tam Lin. There are some key differences. First, it's about siblings rather than lovers. More importantly, it's a tragedy. The story was first published by Allan Cunningham in the London Magazine, and again in 1822, in Cunningham's Traditional Tales of the English and Scottish Peasantry.

The story begins with a quote from Tam Lin (spelled Tamlane here). It’s a triumphant stanza, in which the heroine rescues Tamlane, and the fairy queen declares, "She that has won him, young Tamlane, has gotten a gallant groom.” Although the wording is slightly unique, it is very close to many of the versions in the Child Ballads, which would be published in the 1860s. (The oldest confirmed written version of Tam Lin is dated 1769, but the ballad probably goes back further.) After this quote, the story introduces the valley of Corriewater, where many of the countryfolk believe fairies still dwell. The fairies often woo human youths and maidens away to be their lovers, and people who see their nighttime processions often spot dead relatives among them. The narrator then introduces “the traditional story of the Cupbearer to the Queen of the fairies.” There is a framing device with a group of countryfolk telling the story, different people chiming in to add their own perspectives. The countryfolk introduce the tale of the twins Elphin and Phemie Irving. When the twins are sixteen, their father drowns trying to save his sheep from the river known as the Corriewater. Their mother dies of grief seven days after his funeral. The twins are very close, and both remarkably beautiful. (At this point, one of the storytellers bursts into a song, “Fair Phemie Irving.”) When the twins are nineteen, there’s a drought. Elphin begins driving their flock over the dried-up Corriewater to reach better pastures. One evening, Phemie is waiting for her brother and sees a vision of him entering the house. However, when she goes to check on him, he’s vanished. She screams and goes comatose. Her neighbors, who come to check on her, can’t rouse her until the following morning, when a girl mentions that the Corrie has flooded and some of the Irvings’ sheep have been found drowned. Phemie immediately wakes up, wailing that “they have ta’en him away." She believes she saw the fairies charm Elphin away, for his horse wasn't shod with iron. She denies that he was drowned, and swears she’ll win him back. The superstitious townsfolk begin to gossip, many of them believing Phemie’s account. The storming and flooding worsen. When the storms finally clear, the local laird discovers Phemie seated at the foot of an oak tree within a fairy ring. She sings "The Fairy Oak of Corriewater." In her song, the fairies dance around the haunted oak, and the Elf-queen brags that, "I have won me a youth...the fairest that earth may see; This night I have won young Elph Irving My cup-bearer to be. His service lasts but for seven sweet years, And his wage is a kiss of me." Phemie (though she isn't named in the song) bursts into their dance. The Elf-queen and Elphin climb onto their horses, but Phemie grabs Elphin and calls on God for help. Elphin transforms into a bull, a river, and a raging fire. At this last transformation, Phemie lets go. In the final verse, the elves sing tauntingly that if she had held on through the fire and kissed her brother, she would have won him back. Phemie finishes her song, raving with grief, and the laird carries her home. At the same time two shepherds return bearing Elphin’s body, finally recovered from the river. He drowned trying to save their sheep. When Phemie sees the body, she laughs and says it’s nothing but a lifeless image fashioned by the fairies to fool them all. On Hallowmass-eve, when the spirits wander, she will wait at the graveyard and try again to capture Elphin from the fairy cavalcade. Most of the superstitious countryfolk believe her. But the morning after Hallow-eve, Phemie is found frozen to death in the graveyard, still waiting for her brother. Background Allan Cunningham was a Scottish author and songwriter. This book, Traditional Tales, is clearly literary; anything collected has been polished and framed in his style. In the foreword, Cunningham wrote, “I am more the collector and embellisher, than the creator of these tales; and such as are not immediately copied from recitation are founded upon traditions or stories prevalent in the north." He doesn't provide further information, so we don't know what class "Elphin Irving" might have fallen into. Was it a story he heard directly and wrote down? Or was it “founded upon traditions”? Did it draw inspiration from Tam Lin? A sidenote: in 1809, Cunningham was supposed to collect old ballads for Robert Hartley Cromek’s Remains of Nithsdale and Galloway Song. However, Cunningham instead submitted his original poems, written in the style of ballads. Cunningham's biographer pointed out that other poets around the same time sometimes committed similar deceptions, presenting their own work as ancient stuff. Analysis "Elphin Irving" is a story within a story within a story. In level one, the narrator listens to a story being told by a group of countryfolk. Level two is the tragic but mundane tale of the death of the Irving family. Level three is Phemie's account of her supernatural experience. It’s left ambiguous whether the supernatural elements are real. The only one that really seems squarely stated is that Phemie saw her brother's apparition at the moment of his death. Also, lines blur between the different levels. Rumors and superstitions are threaded through the narrative, and it’s sometimes hard to recall whether we’re reading the words of the peasant characters in the story, or the people sitting about listening in the frame narrative. As pointed out by Carole G. Silver, the fascination of the story comes from both the familiar trope of the fairy kidnapping, and "the author's reasoned hesitation between natural and supernatural explanations of events" (Strange and Secret Peoples, 14). Cunningham loved fairy-stories, but here, he would not commit one way or the other. We are never fully sure whether the fairies are "real." The fairy plotline parallels the story of Tam Lin or Tamlane. This is explicit in the text, and the narrator draws attention to it with the opening excerpt. (Tamlane is also mentioned in "The King of the Peak," another story in the same book.) In “Tam Lin,” the heroine keeps hold through her true love’s transformations and wins him away from the faeries. Cunningham quotes the part of "Tam Lin" where the Fairy Queen accepts defeat. But when Phemie tries to follow that example, she fails, and the elves depart with mockery. Although Tam Lin has a happy ending, in similar folktales, it could sometimes be a toss-up. Tam Lin and Elph Irving are unusual in having a girl as the rescuer; it's typically a man pursuing his supposedly dead (actually kidnapped) wife. In the Irish tale of "The Recovered Bride," he succeeds. But in another story, a Lothian farmer attempts to rescue his wife on Halloween, but loses his nerve and will never have another chance. In "The Girl and the Fairies," two young men fail to rescue a girl from the fairies' procession, and the fairies promptly murder her. A similarly bloody fate awaits an abductee whose husband is held back by neighbors from approaching her (Napier 29). Phemie chooses two classical places to try to recover Elphin - first a fairy ring, and then the local graveyard on Halloween night. On both occasions, she fails. Ultimately, Elphin and Phemie repeat their parents' fate. Like their father, Elphin drowns trying to save their sheep in the very same river. Phemie dies of grief just like their mother. The Irving family is the subject of many rumors, and there are implied ties to the fairies. One possibility is that Elphin was taken by the fairies to be someone’s lover (supported by the Fairy Queen’s talk of kissing him). But it may be more complicated than that. One person claims that the twins’ mother was related to a witch. It is also said that every seven years, the fairies turn over one of their children as a kane (tenant's fee) to the devil. They are allowed to steal a human to offer in their place. This might imply that this is why Elphin was taken, but another rumor claims that Elphin actually is one of those doomed fairy “Kane-bairns,” and was left among humans to avoid this fate. Thus, he isn't really stolen by the fairies, but is returning to his biological relatives. I’ve been skeptical of the idea that changelings are related to the fairy hell-tithe – an idea that is often attributed to “Tam Lin” but doesn’t actually appear there. Tam Lin is in danger of being tithed to Hell, but there are no changelings mentioned in the ballad (Tam may even be a fairy himself in some versions). However, here we do have a story where the two concepts are linked. The fairies' "debt to Hell" was also mentioned in Matthew Gregory Lewis' poem "Oberon's Henchman; Or The Legend of The Three Sisters," written in 1803. So the idea was definitely present in authors' minds in the early 1800s. But I can't help scratching my head at the fact that both Cunningham and Lewis, when writing these stories, directly referenced Tam Lin in the text or in footnotes. Evidence of a tradition, or evidence that Tam Lin was popular? Elphin’s relationship with the fairies is ambiguous, as he seems happy to serve them in exchange for a kiss from the Fairy Queen. He even seems ready to flee from Phemie. His name sounds like Elfin, highlighting his connection to the otherworld. In the song, the fairy queen shortens his name simply to Elph; now he is not just elf-like, but truly one of them. It may be of note that Phemie's name is short for Euphemia (Greek for "well-spoken") and a vital part of the narrative comes from her words, spoken or sung. Also, the family surname of Irving comes from the name of a river - fitting for a character who drowns. The elaborate nature of "Elphin Irving" raises questions about its authenticity. See the flowery writing style, the nested framing devices, and the ambiguity of the fairies' existence. By including the contrasting excerpt from Tam Lin, the narrator is practically screaming for people to compare them. The science of folklore and the focus on verifiable sources were only beginning to develop when Cunningham wrote, but we know that he was willing to fake traditional material. That does not reflect well on him. Reviewing Cunningham's book, Richard Mercer Dorson stated bluntly that "traditional tales they are not, and they might more accurately have been titled 'Literary Tales Faintly Suggested by Oral Traditions of the Scottish Peasantry.'" (History of British Folklore, 122) Carole G. Silver summarized "Elphin Irving" as "really a version of the ballad of Tamlane." Cunningham would not be the only person to write their own version of Tam Lin. Sophie May's Little Prudy's Fairy Book (1866) included a version titled "Wild Robin". Like "Tam Lin," there's a happy ending; however, like "Elphin Irving," it's mainly prose with excerpts from the Tam Lin ballad, and it also makes the main characters siblings rather than lovers. In the case of Wild Robin, it seems like this change was purely to remove the sexual elements and tone it down for children. It is impossible to say why Cunningham might have made this change, though. I lean towards the theory that Elphin Irving was Cunningham's own creation, inspired by folklore and especially by Tam Lin. What do you think? Leave your thoughts in the comments! Sources

A soldier's son sets out to make his fortune, saying goodbye to his widowed mother. On the way, he pulls a thorn from a tigress's paw; the grateful tigress, who happens to be able to talk, gives him a box in thanks and tells him to open it once he has carried it nine miles. However, the further he goes, the heavier the box becomes, until at eight and a quarter miles, it's impossible to carry. Saying that he believes the tigress was a witch, he throws the box down. The box bursts open, and out steps a little old man, one hath high (19 inches), with a beard that trails on the ground. The little man, who is highly cantankerous, is named Sir Buzz.

"Perhaps if you had carried it the full nine miles you might have found something better; but that's neither here nor there. I'm good enough for you, at any rate, and will serve you faithfully according to my mistress's orders." The soldier's son asks for dinner, and Sir Buzz immediately flashes away to the nearest town. There, he shouts at shopkeepers who don't notice him due to his size, and then leaves each shop with a massive bag of supplies, carrying them without any trouble. The soldier's son and Sir Buzz then eat a meal. Eventually the two reach the king's city, where the soldier's son sees the king's daughter, Princess Blossom. This princess is notable in that she weighs no more than the equivalent of five flowers. The soldier's son is smitten, and begs Sir Buzz to carry him to the princess. Although he complains, Sir Buzz - "who had a kind heart" - does so He takes him to the princess's bedchamber in the middle of the night. The princess is frightened at first, but is won over by the soldier's son, and the two talk all night and finally fall asleep at dawn. In order to prevent the soldier's son from being discovered, Sir Buzz carries off the bed with them both in it to a garden, uproots a tree to use as a club, and stands guard. As soon as it's noticed that the princess is missing, a huge search ensues. The one-eyed chief constable tries to search the garden, encounters a tiny screaming man waving a tree around, and returns to the king with this wholly original statement: "I am convinced your majesty's daughter, the Princess Blossom, is in your majesty's garden, just outside the town, as there is a tree there which fights terribly." Sir Buzz fights off anyone who tries to come near, and the soldier's son and Princess Blossom set off happily on their own. The soldier's son feels that he has made his fortune, and tells Sir Buzz that he can return to his mistress. However, Sir Buzz leaves him with a hair from his beard, telling him to burn it in the fire if he's ever in trouble. The princess and the soldier's son promptly get lost in a forest and reach the point of starvation. A Brahman invites them to his home, which is filled with riches. He tells them they may open any cupboard except the one locked with a golden key. Of course the soldier's son does so anyway, and in the forbidden cabinet finds a collection of human skulls. Their rescuer is not a Brahman, but a vampire who plans to eat them. At that very moment, the vampire steps in, but the quick-thinking Princess Blossom puts Sir Buzz's hair into the fire. Sir Buzz and the vampire then have a competition of transformations; the vampire turns into a dove and Sir Buzz into a hawk, and so on. The vampire becomes a rose in the lap of King Indra, and Sir Buzz becomes a musician who plays so wonderfully that Indra gives him the rose. Finally, the vampire turns into a mouse, and Sir Buzz becomes a cat and eats him. Sir Buzz then returns to Princess Blossom and the soldier's son and announces, "You two had better go home, for you are not fit to take care of yourselves." He takes them and all the vampire's riches back to the home of the hero's mother, where they live happily ever after, and Sir Buzz is never heard from again. This story has remained a favorite of mine because it's so colorful and silly. There's also a lot going on and all kinds of random details. Background The story was collected by Flora Annie Steel, a British woman whose husband worked in India in the Indian Civil Service. Steel published this story as "Sir Bumble" in the Indian Antiquary in 1881, and she wrote that the story was well-known in the Panjab and was "Muhammadan" in origin. It also appeared in her 1881 work Wide-Awake Stories: A Collection of Tales Told by Little children, between Sunset and Sunrise in the Panjab and Kashmir (1884). She changed the name to "Sir Buzz" in Tales of the Punjab: Told by the People (1894). The different versions are nearly identical. She wrote in the Indian Antiquary that "It possesses considerable literary merits remarkable from their absence in most Panjabi tales. The treatment is humorous and in places poetical, and the tale as a whole gives the idea of its having been at some period committed to writing." In Wide-Awake Stories, she stated she heard it from a Muslim Panjabi child, name unknown. The Tale Type and Characters The story falls into Aarne-Thompson type 562. Similar tales include "Aladdin" and Hans Christian Andersen's "The Tinderbox." In tales of type 562, a man seeking his fortune (often a former soldier, in this case the son of a soldier) encounters a sorcerer, witch, or someone else who gives them a magical object. This object grants them command of a magical servant - a genie, a giant, a gnome, or a trio of magic dogs. With this servant's help, the man kidnaps and marries a princess. Unfortunately, he gets into trouble and somehow loses access to the magical servant. At the last moment, he gets the servant back and everything works out. "Sir Buzz" has some unique touches. In many versions the sorcerer or witch is at odds with the hero, and the hero may even kill them to gain the magic source. But the tigress seems like a decent sort, and the hero willingly sends Sir Buzz back to her in the end. In most tales, the hero winds up becoming king when he marries the princess (sometimes executing her father in the process), but here the hero and princess return to his poor mother's home, and we never hear anything else about the kingdom. Heroes of Tale Type 562 tend to be jerks, but the hero of Sir Buzz is a hapless but honest type. There are some touches of other tales. The section in the vampire's house with the forbidden key is right out of "Bluebeard," and the finale of Sir Buzz's battle is similar to "Puss in Boots." According to Flora Annie Steel, the tigress was described in the original story as a bhut or evil spirit. Were-tigers feature in many Indian stories and could be dangerous villains. The tigress is unusual here in that she is apparently benevolent. The vampire, in the original, was a ghul, and Steel explains that the one eye of the chief constable (kotwal) indicates that he's evil. Princess Blossom's name is Bâdshâhzâdi Phûlî (Princess Flower) or Phûlâzâdî (Born-of-a-flower). Her unusual weight is a well-known motif in Indian folktales, known as the five-flower princess (Grounds for Play: The Nautanki Theatre of North India, p. 308). Her weight shows how delicate and almost otherworldly she is. We never hear of Princess Blossom's family or kingdom again. She does seem to be fairly capable and quick-thinking, though. Sir Buzz, the incredibly powerful, irritable and violent sprite, is clearly the star of the story. His personality stands out, which can be rare in this tale type. As well as being opinionated and a strong source of the slapstick comedy throughout the tale, he seems to have a genuinely caring relationship with the hero. His name is Mîyân Bhûngâ, which means "Sir Beetle" or "Sir Bumble-bee." The image of a tiny man with a long beard trailing on the ground is a common one, appearing in tales from across the world (a few are listed in my Thumbling Project here). A character with the exact same description is the tiny blacksmith in the story of Der Angule (Three-Inch), a Bengali Thumbling tale. Further reading "The Water-Horse of Barra" is a fairytale that's stayed with me since I read it years ago. It is especially striking because it takes one of the cruelest monsters in Scottish legend and turns him into a redeemable hero. The story has been presented as a folktale, but I began to wonder if it was really traditional or not.

The tale appeared in Folk Tales of Moor and Mountain by Winifred Finlay (1969). On Barra, an island off the coast of Scotland, there lived a water-horse or each-uisge - a shapeshifting water spirit, similar to the kelpie. The water-horse went seeking a bride, and captured a young woman by tricking her into placing her hand on his pelt. However, the quick-thinking girl invited him to rest a while, and he took human form in order to sleep. While he slept, she placed a halter around his neck, trapping him in horse form and forcing him to do her bidding. She then kept him to work on her father's farm for a year and a day. However, during that year and a day, he learned love and compassion. Rather than depart for Tìr nan Òg (the Scottish Gaelic form of Tir na nOg, the Irish otherworld), he underwent a ritual to become truly human, losing even the memory of being a water-horse. He and the girl married, and lived happily ever after. Winifred Finlay was an English author who published numerous folklore-inspired novels and collections of folktales. In Moor and Mountain, she gives no sources, leaving it mysterious how she found these stories. This should be an immediate cue to look at them critically. Some of them are familiar. Midside Maggie and Tam Lin are well-known, and "Jeannie and the fairy spinners" is a retelling of the story of Habetrot. However, others are less familiar to me, such as "The Fair Maid and the Snow-white Unicorn" (which, like "Water-Horse," features a girl marrying a handsome man who used to be a magical horse). I have never found an older equivalent of Finlay's water-horse romance, although it has been retold in other collections. It appeared as "The Kelpie and the Girl" in The Celtic Breeze by Heather McNeil (2001) and "The Kelpie Who Fell in Love" in Mayo Folk Tales by Tony Locke (2014). A running theme in Finlay’s books is that the world of fairies and magic has ended, with the modern human world taking its place. In "The Water-horse of Barra," "Saint Columba and the Giants of Staffa," and "The Fishwife and the Changeling," magical creatures must either leave this world forever, or assimilate and become ordinary humans. "The Water-Horse of Barra" bears an especially strong resemblance to "The Fishwife and the Changeling." Both tales follow a traditionally evil entity who is won over by the love of a human woman, and who opts to become mortal and stay with her rather than depart for the Land of Youth. In the second case, the woman is a devoted mother who adopts a fairy changeling and raises him alongside the child he was meant to replace. Although I adore this take on the changeling mythos, it is strikingly different from most folktales, where any compassion towards changelings would be unusual. In a tale recorded in 1866, a parent who accidentally winds up with both babies still resorts to the threat of torture to get rid of the fairy child (Henderson, Notes on the Folklore of the Northern Counties of England and the Borders, 153). The idea of a changeling and the original child raised as siblings is fairly new, although it seems to be growing popular in recent fiction - see, for instance, The Darkest Part of the Forest by Holly Black (2015) and The Oddmire: Changeling by William Ritter (2019). Back to the Water-Horse of Barra. This tale features many of the usual kelpie tropes. A person who touches the water-horse will find herself trapped as if glued to his skin. However, if the creature is haltered or bridled, he becomes docile and tame - at least as long as the halter is in place. In other ways, however, it is strikingly atypical. Kelpies are usually totally murderous. Although they are often found pursuing women, it is generally to eat them. There is an older tale about a Water-horse of Barra. However, this tale is very short and takes a gruesome turn. A young woman of Barra encountered a handsome man on a hill. They chatted, and eventually he fell asleep with his head in her lap. However, she noticed water-weeds tangled in his hair, and realized to her horror that he was a water-horse. Thinking quickly, she cut off the part of her skirt that his head was resting on, and slipped away to safety. However, some time later when she was out with friends, he reappeared and dragged her into the lake. All that was ever found of her was part of her lung. This story was told by Anne McIntyre, recorded by Reverend Allan Macdonald of Eriskay, and published by George Henderson in 1911. (Henderson, Survivals in Belief Among the Celts) It is rare for the kelpie to be seen with a softer side. J. F. Campbell gives a one-sentence summary of this story type in Popular Tales of the West Highlands, where he states that the kelpie "falls in love with a lady." The summary ends with her finding sand in his hair and presumably reacting with horror. The phrasing is fairly soft, suggesting that a kelpie could really fall in love, but all of the other kelpie stories Campbell gives are bloody and dark. I wonder if "falls in love" was a euphemism on Campbell's part. One other point of interest is a song, titled "Skye Water-Kelpie's Lullaby" (Songs of the Hebrides) or "Lamentation of the Water-Horse" (The Old Songs of Skye). In this song, the singer mournfully begs a woman named Mor or Morag (depending on translation) to return to him and their infant son. This song has been interpreted as the story of a water-horse whose human bride has left him after realizing his identity. Outside the kelpie realm, there is another story with key similarities - the Scottish ballad "Lady Isabel and the Elf Knight." In this song, Isabel hears an elf-knight blowing his horn and wishes for him to be her lover. At that very moment, the elf knight leaps through her window and takes her riding with him to the woods. It’s all fun and games until he gets her into the remote wilderness, where he declares that he has murdered seven princesses and she will be the eighth. When begging for mercy doesn’t work, Isabel persuades him to relax and rest his head on her knee for a little while first. She uses a “small charm” to make him sleep, then ties him up with his own belt and kills him with his own dagger. Finlay’s heroine has strong Isabel vibes. Her suggestion of resting, and then her capture of her would-be kidnapper, is clearly parallel. When she calls on the bees to buzz and lull the water-horse to sleep, it's similar to Isabel's "charm." “Lady Isabel and the Elf Knight” is one member of a wide family of similar tales, although the plots vary and “Isabel” is somewhat atypical. Of course, the Elf Knight is not a kelpie. His native habitat is apparently the forest. However, in other versions, the serial killer’s method of killing is drowning (see "The Water o' Wearie's Well" and "May Colvin"). Francis James Child suggested that in these versions "the Merman or Nix may be easily recognized". A Dutch neighbor, “Heer Halewijn,” has been compared to a Strömkarl or Nikker. Unfortunately, as critics quickly pointed out, the logic fails since the serial killer dies by drowning in these versions, which would not make sense for a merman. The theory has stuck around despite lack of evidence. The rather unique “Lady Isabel” has faced scrutiny; the unclear origins have led to many different theories, and some scholars have even suggested that it was a fake written by its collector Peter Buchan. This will have to be a post for another time. Insofar as our current subject, “Lady Isabel” and the connected water-spirit theory are definitely old and well-known enough that Finlay could have been familiar with them. However, like the old kelpie stories, these ballads are not romances but cautionary tales. The stories in Folk Tales of Moor and Mountain are familiar folk tales, but they are all Finlay's retellings. Her "Water-Horse of Barra" is probably a reimagining of the older Barra water-horse tale. (Perhaps it's influenced by "Lady Isabel," although this might be more of a stretch.) In both Barra stories, a girl finds herself cornered by a kelpie in the form of a handsome man, and must figure out an escape as he lies sleeping. However, Finlay rewrote it with a gentler, family-friendly ending. Finlay's water-horse is tame and toothless even at the beginning: "he was very good-natured and never caused anyone harm." The only shocking thing about his diet is that he eats raw fish. Older tales often had sexual elements; a disguised kelpie shares a victim's bed to prey on her, and sleeping with your head in someone's lap is a euphemism for sex (note especially that the girl cuts her skirt off to escape). Finlay's water-horse never does anything so improper as sleep in the girl's lap; instead he stretches out in the heather to rest. In folktales, kelpies suck girls dry of blood, or devour them and leave only scraps of viscera. But Finlay's heroine is never in fear for her life. See her reaction: “He really is extremely handsome... but I have no intention of marrying a water-horse and spending the rest of my life at the bottom of a loch.” Finlay inverts the usual setup: here, the girl captures the kelpie. The kelpie is the one carried into a new realm and affected by their encounter. Not only is this ending more cheerful, but it ties in with Finlay's running theme. The time of magic ends to make way for a modern era. Supernatural power is exchanged for love, whether that love is romantic, familial, or belonging to a community. Regardless of its origins, Winifred Finlay's romantic tale of a good-hearted water-horse has earned its own place in modern folklore. This shows a shift in how we comprehend and retell these stories. In 19th-century storytelling, kelpies and changelings would have been totally irredeemable, definitely not beings you'd want to invite into your home. Now, however, you can find stories removed from folk belief where kelpies and changelings are the heroes and main characters. There's a growing tendency to give even the most terrifying monsters of legend a chance for redemption. Further Reading

This is a weird and obscure tale, and one of my favorites. It appeared in Andrew Lang's Yellow Fairy Book in 1889, adapted from a tale of the Armenian people living in Transylvania and Bukovina. (Bukovina is a Central European region, which was once part of Moldavia and is now divided between Romania and Ukraine.)

In the story, a childless woman accidentally swallows an icicle, and gives birth to a little girl "as white as snow and as cold as ice," who can't bear any kind of heat. Then the same woman is struck by a flying spark from their fireplace, and gives birth to a boy "as red as fire, and as hot to touch." This is part of the widespread motif of pregnancy beginning with eating. The siblings avoid each other as they grow up, since they can't bear each other's temperatures. But when their parents die, they decide to go out into the world. They wear thick fur coats so that they won't hurt each other, and they're very happy together. Eventually, the Snow-daughter meets a king who falls in love with her and makes her his wife. He builds her a house of ice, and makes her brother a house surrounded by furnaces, so that they can both be comfortable. One day, the king holds a feast. When the Fire-son arrives, he has now grown so hot that no one can bear to be in the same room as him. This is, as you might expect, kind of a mood-killer. The party is totally ruined. The king yells at the Fire-son, who responds by going full-on supervillain and incinerating him. The now-widowed Snow-daughter attacks the Fire-son. The siblings have a battle "the like of which had never been seen on earth," and which is left up to the reader's imagination. However, at its conclusion, the Snow-daughter melts like the icicle she came from, and the Fire-son burns out like a spark, leaving only cinders. And that's it. I think it's interesting that snow is feminine here and fire masculine. This also not the only story about snow-related children. It's similar to the Russian "Snegurochka" (also known as "Snegurka" or "Snowflake"). There, a childless couple makes a snow sculpture which turns into a little girl. When she tries to play a game jumping over a fire, she melts away into mist. This tale type, "The Snow Maiden" or Aarne-Thompson 703, has the moral that you can't escape your nature. The Snow Daughter and the Fire Son varies in that the fire is actually the snow-child's sibling. Resources

In most traditional versions, Cinderella’s ball is a multi-night affair. She visits on three nights and dances with the prince three times. Often she wears more elaborate dresses each night, building more and more on the concept. She loses her shoe on the third night. Both Perrault’s Cendrillon and the Brothers Grimm’s Aschenputtel follow this model.

The rule of three also shows in versions where she has two stepsisters. Cinderella is one of three rivals. Her two stepsisters go to the ball first and try on the shoe first. Cinderella is the triumphant final contestant. The Rule of Three is a common storytelling or rhetorical technique across western literature including folktales. Even in modern times, think how many things come in threes, like the Three Musketeers. The number is also recurrent throughout the Bible (Jonah in the whale for three days) and in Christian teaching (like the Trinity). Three is the smallest possible number that’s still recognizable as a pattern. Patterns of three make the tale feel more satisfying, complete, or amusing, without the repetition becoming boring. In many modern retellings, however, Cinderella goes to one ball only. I think this began with stage adaptations such as pantomimes. Films followed suit, including the 1914 Cinderella film starring Mary Pickford, and the animated Disney film from 1950. In storytelling, it’s easy to skim quickly over the details of the ball. In stage or cinema, three spectacles of a kind might start to drag. These are visual adaptations and the fairytale’s exact repetition is not going to work. You could have three identical ball nights, or try to vary it up and make each occasion different (with all the set or animation costs involved) . . . or you could simply summarize it into one. Does this mean something has been lost? I don’t think so. The formats of the telling are different – a play, movie or a novel is very different from an oral folktale, and the same things won’t necessarily work across different mediums. Movies frequently condense their source material. Also, audiences’ tastes change. In the original, the three-night ball is really the main plot. Cinderella is a heroine completing a series of trials. Can she escape her family’s attention each night? Can she get another dress from her supernatural benefactor? Can she wow the prince each night and then slip away afterwards? In some versions she becomes a trickster, hiding behind a Clark Kent-esque disguise and savoring her own private joke. You can imagine Perrault’s Cinderella winking at the audience as she asks her sisters about the mysterious lady at the ball. The Grimm Cinderella gets up to some hijinks as she evades the lovelorn prince, scaling a tree or hiding in a pigeon coop. But modern retellings typically leave this out. In the fairytale, Cinderella and the prince develop a connection over three nights; initial attraction leads immediately to marriage. He can’t even recognize her through her rags and soot, being only able to identify her by her shoe. Not particularly romantic. Modern versions typically focus on the romance and on giving Cinderella a goal beyond just going to a party and finding a husband. The 1998 film Ever After, Marissa Meyer’s 2012 novel Cinder, and Disney’s 2015 live-action remake all spend the majority of the story building up Cinderella’s relationship with the prince, and her own personality and life goals. Instead of ball attendance being the main plot, the ball is a single dramatic scene. Cinderella gets one shot at wowing her prince, and so the ball is that much more significant. Gail Carson Levine’s Ella Enchanted (my favorite Cinderella retelling of all time) goes for three balls. However, Levine – like the other authors mentioned – builds a more unique plot and has Ella fall in love with her prince long before the festival. (I think the movie adaptation reduced the celebrations to a single coronation ball, though I have not watched it). The Grimm-inspired musical Into the Woods features three balls, but at least in the film adaptation, they take place mostly offscreen. The ball is not the focus. Instead, the focus is on Cinderella fleeing on three consecutive nights, and the slightly different events each time. Again, it’s avoiding too much repetition. Another thing: particularly if it’s a contemporary or high-school retelling, one-night events are often more common than multi-night recurring festivals. The 2004 movie A Cinderella Story made it a Halloween dance. Some of these stories still include the secret identity element by making it a masquerade ball, or having Cinderella not realize her beloved is the prince at first. Contemporary versions have an advantage in that the romantic interests can chat online to begin with, preserving their anonymity until it's time for the big finale. So it makes sense for the story to be updated. But the new emphasis on Cinderella having more personality, or more chemistry with the prince, is separate from the fact that many versions just have one ball. A lot of this may be the effect of film. Cinderella has been retold many times, and today a lot of people get their main exposure to fairytales through movie format. Disney is one of the main heavy-hitters, but even earlier versions (like the Mary Pickford film) had just one ball. You don’t see as many versions of Cinderella’s close cousin All-kinds-of-fur or Donkeyskin (which is probably rare because of the incest theme). I’ve seen three versions, and all featured the three balls. This story is a little different because it is an important plot point that the heroine has three different dresses, and of course she has to show them all off. However, I can’t think of any versions where the three dresses are condensed into one. If Disney had been daring enough to adapt this tale, we might have a standardized simplified version as we do with Cinderella. (While we’re on this subject, I would heartily recommend Jim Henson’s TV episode “Sapsorrow” – a combination of Cinderella and Donkeyskin including a dark spin on the glass slipper, where a king is unhappily bound by law to marry whoever his dead wife’s ring fits.) Other Blog Posts One of my favorite childhood fairytales was the expressively titled "The Two Sisters Who Envied Their Cadette" (or in more modern language, "The Two Sisters Who Envied Their Younger Sister.") This is one of the Arabian Nights, but it's actually part of a group of "orphan tales," which appeared in Antoine Galland's translation from the early 1700s, and not in the original manuscripts. Some, like Aladdin and Ali Baba, are actually more well-known than the original Nights, and I have to say Periezade was my absolute favorite when I read a collection as a kid.

The story begins with a king named Khusraw Shah or Khosrouschah. There were a few real Persian kings named Khosrau. This story’s Khosrau Shah comes off as capricious and murderous, but we'll get to that in a minute. He overhears three sisters talking. One dreams of marrying the king's baker, another of marrying the Sultan's chef, and the youngest and most beautiful says that she would marry the Sultan. While the first two make their wishes out of gluttony, the youngest is said by the narrator to have more sense. Amused, the Sultan has them fetched to the palace and performs all three weddings on the spot. Unfortunately, this sows resentment; the older sisters grow jealous and plot their sister's demise. Over the next few years, she gives birth to two sons and a daughter, and each time her sisters replace them with a puppy, a kitten, and a wooden stick that they pass off as a molar pregnancy. They secretly put the babies in a basket and boat them off down the canal. The king initially wants to execute his wife straight off, but his advisors talk him down and he decides to instead have her imprisoned on the steps of the mosque, where everyone on their way to worship must spit on her. The superintendent of the palace gardens, with fantastic timing, happens to be in the area each time a baby comes floating along the river. He realizes that they must have come from the queen's apartments, but decides it's better not to get involved, and just raises them as his own. He and his wife pass away before they have the chance to explain the children's true origins, so the king's children - Bahman, Perviz and Periezade - are left to live in their isolated house, living a wealthy and comfortable yet solitary life. The boys are named after Persian kings - Perviz's name means "victorious" and I found out that one of the real Khosraus had "Parviz" as a byname. Periezade's name is derived from "peri" or fairy. The narrator takes note that Periezade is formally educated and physically active just as much as her brothers. One day, an old woman tells Periezade of three marvelous treasures: Speaking Bird, the Singing Tree, and the Golden Water. Periezade is overcome with longing for these things (I had forgotten before I reread it how weirdly obsessed she becomes). She pleads so much that her oldest brother Bahman agrees to go and find them, leaving behind a magical dagger that will become covered in blood if he dies. Soon enough the dagger turns bloody, and Perviz does the same, leaving Periezade with a string of pearls that will get stuck if he's in danger. When Perviz also falls into peril, Periezade disguises herself as a boy and sets out after them. Now, both Bahman and Perviz had encountered an old man on their journey, and Periezade soon does the same. In many stories, when a trio of siblings encounters an old beggar in the woods, it's a chance to contrast the nobler and kinder youngest sibling. However, in this case all three siblings are courteous and generous to the old man who warns them of the dangers ahead. The difference is in how they take his warning into account. He tells them that as they climb the mountain to the Speaking Bird, they must not turn back, even though voices will taunt or frighten them. The brothers each climbed the hill, filled with over-confidence, and end up turning around only to be transformed into black stones. Periezade, however, has the practical foresight and self-knowledge to stuff her ears with cotton. Not only does she get the bird, but it tells her how to restore her brothers and all the other travelers to life with the magical Golden Water. They return home with the treasures, and it so happens that the king encounters the brothers while they're hunting in the forest. They invite him to dinner. The Speaking Bird advises Periezade to serve a cucumber stuffed with pearls. Baffled, the king says that it makes no sense, and the Speaking Bird tells him that it makes just as much sense as a woman giving birth to animals. The Bird reveals the whole backstory, and the king embraces his long-lost children, sends the wicked sisters to be executed, and restores his queen to favor. (Even though I feel like a much more satisfying ending would be for her to take the kids and run far, far away.) Background Periezade's story is an example of Aarne-Thompson Type 707, "The Bird of Truth" or "The Golden Sons." Another version does appear in the Arabian Nights, known as "The Tale of the Sultan and his Sons and the Enchanting Birds." European versions are widespread. The persecuted wife accused of giving birth to animals, who is imprisoned but later restored to favor when her grown children return, is a very common motif that appears in all sorts of stories. Sometimes all of the children are boys. Sometimes it's twins, a boy and a girl, or a girl and several boys. Often, they are connected to stars or other celestial bodies, such as having a star on their foreheads. The blame on the queen in these stories hints that she indulged in bestiality to produce animal children, or she is responsible for bearing not a child but a molar pregnancy, disgracing her husband either way. The old woman who tells Periezade about the treasures remains mysterious. In some versions, it’s actually the wicked aunts or one of their servants, trying to get rid of the children now that they know they’ve survived. It seems this element was lost or confused in the Galland version. In some other tales, though, the old woman is a benevolent figure. Not all versions feature the quest for the magical objects, but the typical ending is that the king encounters the grown children - perhaps in the woods, perhaps at his own wedding to a second wife - and their story comes out, causing him to repent of his treatment to his wife. The story has ancient roots. A similar tale appeared around 1190 in Johannes de Alta Silva's Dolopathos sive de Rege et Septem Sapientibus. A lord marries a fairylike maiden who gives birth to septuplets, six boys and a girl, each born wearing a gold chain. The jealous mother-in-law swaps the children for puppies, and the easily fooled husband punishes his wife by having her buried up to the neck in the middle of the woods. The children survive and grow up in the forest; each has the power to transform into a swan, but the mother-in-law discovers them and steals the boys’ golden chains, leaving them trapped in swan form. The sister escapes this fate and continues to take care of her brothers, and when the lord finds out, he has the chains returned to his sons and frees them. (One son, whose chain was damaged, is left as a swan.) This is closer to the tale type of the Swan-Children, but there are still familiar elements. The more modern versions of "The Wild Swans," like Hans Christian Andersen's story, have the sister imprisoned, persecuted and accused of murdering her own children. Perhaps not incidentally, at the end she saves her brothers and regains her children at the same time, and is finally able to speak and tell her husband her whole backstory. The oldest known version of the Periezade variation is "Ancilotto, King of Provino," in The Facetious Nights of Straparola from the 1550s. The heroine is named Serena. This version has the quest as the villainous mother-in-law and aunts’ attempt to get rid of the children. The similarities in general are close enough that Galland might even have been directly influenced. Galland's contemporary, Madame D'Aulnoy, wrote her own version of the story as "Princess Belle-Etoile and the Prince Cheri." Sources

Michael Drayton (1563-1631) was an English poet whose work varied from political to mythical. His poem "Nymphidia" was published in 1627, at the height of a new fad for tiny fairies started by his contemporary William Shakespeare. "Nymphidia" is also known by the title “The Court of Fairy” or in some later editions “The History of Queen Mab”. It has remained a classic of fairy literature ever since.