|

One thing I didn't realize until I started researching folklore in depth is how much drama there is behind the scenes. For instance, take the story of "The Soul Cages."

The whole thing started when Thomas Crofton Croker began his collection Fairy Legends and Traditions of the South of Ireland. However, as the story goes, he lost his manuscript right before publication. A number of his Irish friends generously lent their help, writing out material and adding the folktales they knew. The result was a collaborative effort between many authors. Croker chose to publish the book anonymously, as the work of many, and it hit shelves in 1825. It was instantly popular. Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm translated it into German as Irische Elfenmarchen in 1826. Croker claimed all credit. Then he got right to work on producing more material. Around 1827, he published Volume 2, but this one was under his name alone. One of the tales in Volume 2 was "The Soul Cages." Here, a fisherman befriends a merrow (merman) named Coomara (sea-hound). Coomara lends him a hat that will let him breathe underwater and invites him to visit his home on the seafloor. They have a nice meal and chat, but as the merrow shows him around, the fisherman notices a strange collection of lobster traps. Coomara explains that they are "soul-cages," containing the spirits of drowned sailors which he traps. The merrow makes out that he's doing the souls a favor by keeping them safe with him, but the Catholic fisherman is horrified. He contrives to get the merrow drunk, and then opens each of the cages to release the souls inside. From then on, the fisherman regularly pulls this trick to release souls as the merrow catches them. Croker noted the story's striking resemblance to the German "Der Wassermann und der Bauer," or "The Waterman and the Peasant," which had appeared in the Brothers Grimm's Deutsche Sagen (1816-1818). In fact, when placed side by side, the stories shared identical plots. "The Soul Cages" is simply a more elaborate retelling of the Grimms' tale with Irish names and stereotypes stapled on. There arose another issue. It seems there was controversy over Croker's manner of attributing sources - or rather, not attributing them. As one example, contemporary poet A. A. Watts wrote in Literary souvenir (1832): ...See Crofton Croker, That dull, inveterate, would-be joker, I wish he'd take a friendly hint, And when he next appears in print, Would tell us how he came to claim, And to book prefix his name – Those Fairy legends terse and smart, Of which he penned so small a part, Wherefore he owned them all himself, And gave his friends nor fame, nor pelf. One of Croker's helpers was the Irish writer Thomas Keightley. He went on to publish his own work, including the highly ambitious collection The Fairy Mythology in 1828. And he was steamed about not being credited properly in Fairy Legends. He said several times that credit wasn't important to him, but he still displayed a strong feeling that he had been used and cheated. In his 1834 work Tales and Popular Fictions, Keightley declared that he was the uncredited source for a large number of tales in the first and second volumes of Fairy Legends. He laid claim to "The Young Piper," "Seeing is Believing," "Field of Boliauns," "Harvest Dinner," "Scath-a-Legaune," "Barry of Cairn Thierna," various pieces of other tales, and - most pertinently at the moment - "The Soul Cages." But it was a collaborative effort, as "another hand" - i. e., Croker - added details to these stories. Keightley adds that he had nothing to do with Volume 3, "which was apparently intended to rival my Fairy Mythology". Although hinting that he has experienced "hostility" over it, he also says he has "been amused at seeing [himself] quoted by those who intended to praise another person." He dismisses Fairy Legends as a bad depiction of Irish culture and dismissively says that he doesn't really care about getting the credit for such a "trifling" book. There are layers of cattiness here. Croker never explicitly denied that Keightley had authored those stories. His combined volume of Fairy Legends in 1834 left out a number of stories, including "The Soul Cages." The new foreword suggested that the removal of these tales would "sufficiently answer doubts idly raised as to the question of authorship." This contributed to public perception that Keightley really had written the stories he claimed. In an 1849 interview, Croker included Keightley in a list of people who helped him with the book, but indicated that they were essentially secretaries "writing, in most instances, from dictation." However, they were all skilled authors and scholars in their own right, and considering his apparent bow to pressure in 1834, this seems suspicious. Collaboration on folktale collections was not uncommon, but in this case there were clearly both confusion and hard feelings. Keightley did not include "The Soul Cages" or any of his Croker-collaboration material in The Fairy Mythology in 1828. But by 1850, a new edition had appeared. This time, Keightley included an English translation of "The Waterman and the Peasant" - and tucked away in the appendix was "The Soul Cages." Here, as a footnote, Keightley made a stunning announcement: We must here make an honest confession. This story had no foundation but the German legend in p. 259 [The Peasant and the Waterman]. All that is not to be found there is our own pure invention. Yet we afterwards found that it was well-known on the coast of Cork and Wicklow. "But," said one of our informants, "It was things like flower-pots he kept them in." So faithful is popular tradition is these matters! In this and the following tale there are some traits by another hand which we are now unable to discriminate. So here we are. "The Soul Cages" was an original creation by Keightley. More than that, it was plagiarized. It was stolen from the Brothers Grimm and not Irish at all. Keightley has drawn harsh criticism from those who noticed the tiny note. Anne Markey called The Soul Cages "an elaborate confidence trick on Croker, Grimm, and subsequent commentators." (However, she also dated Keightley's confession to an 1878 edition, much later.) But was it a confidence trick? Was it revenge against Croker for not citing his sources - an attempt to discredit him? Was it a test to see if Croker would even notice? Honestly, I'm glad that Keightley confessed, even in the sneaky side way he did it. His confession, hidden in a footnote of an appendix of a later edition, was too little, too late. The story had already spread into the public consciousness, and is still circulated by people who never got that easily missed memo. But at least he told the truth at some late point. He even personally wrote to the Grimms to explain. Or so I'd heard. Then I found out that there are reproductions of Keightley's letters to the Grimms in Volume 7 of the series Brüder Grimm Gedenken. Keightley wrote to the Grimms to ask advice and feedback on The Fairy Mythology. When he mentioned Croker, the level of venom was astounding. He called Croker “a shallow void pretender” and “a parasitical plant.” According to him, Croker couldn't even speak German, and when he had corresponded with the Grimms, it had really been Keightley translating everything. In his version of the story, Croker was working on “a mere childs book” when Keightley suggested something grander; Keightley and friends then generously contributed material for two volumes of Fairy Legends. But Croker (a writer of “feebleness and puerility”) hogged the spotlight and insulted Keightley's writing abilities to boot, calling him simply a "drudge" good for nothing but writing down what he was told. Keightley insisted that he had been "defrauded" of the tales he collected for Legends, and that Croker was still trying to one-up him and compete with him. Keightley quickly realized that his colorful account might be taken as unprofessional. In a letter dated April 13, 1829, he backtracked, demurring that he was just an Irishman with "hot blood" - but reiterating that his version contained the hard facts. He explained further, I know not whether you have translated the 2nd vol. of the Fairy Legends or not. If you have not I cannot blame you for Mr. C. intoxicated with the success of the first volume thought the public would swallow any nonsense & he therefore in spite of me put in some pieces of disgraceful absurdity. The history of the legend called the Soul-cages is curious. I had read, in English, to Mr. C. several of your Deutsche Sagen. One morning he called on me & said that he thought the “Waterman" would make an excellent subject for a tale & that he wished I would write it. I objected that we did not know it to be an Irish legend. “Oh what matter! said he, who will know it? I accordingly wrote the tale which is therefore entirely my invention except the groundwork. You will however except the nonsense-verses & some other puerilities which you will give me credit for not being capable of. But the most curious circumstance is that after the Soul-cage was written I met with two persons from different parts of Ireland who were well acquainted with the legend from their childhood. According to Keightley's version, this was no prank or confidence trick - at least not on his part. Croker had the idea to plagiarize the Grimms. If there are any scenes you think are dumb, it's because Croker added them. But it's actually okay, Keightley says, because people really were telling similar stories in Ireland. If this reproduction of the letter is accurate, then I now feel less sympathetic to Keightley. In his casting of blame, he comes off as immature and two-faced. Keightley may not have published his thoughts on Croker in Fairy Mythology, but he made very sure to always include that he had heard the Soul Cages story in Ireland afterwards. He needed that excuse. Admitting he'd fabricated a story torpedoed his credibility as a folklorist. At least this way he could cling to some plausible deniability. He was practically forced to write the story, he claimed, and afterwards he found out it was genuine anyway. No one can really say whether or not he really heard the story in this later context. Anne Markey suggests the story slipped into folklore after its origins in Croker's book, but this depends on timing. Keightley's public confession was later, but he confessed to the Grimms only two years after "The Soul Cages" was published. That was hardly enough time for the story to have seeped into public consciousness, especially when Keightley's new informants had supposedly known the story since childhood. I do not know of any other stories of this type in Ireland. Thomas Westropp, in his "Folklore Survey of County Clare" (1910-1913), noted that he'd found no other examples of this story in Ireland. He expressed "great doubt" on its authenticity. However, we do have the German tale of "The Waterman and the Peasant," and similar tales from Czech areas. "Yanechek and the Water Demon" ends with the main characters drowning and being collected by the demonic vodník. "Lidushka and the Water Demon's Wife" has a happier ending, in which a girl successfully releases the souls in the form of white doves. These tales were identified as Bohemian in origin in Slavonic Fairy Tales (1874) by John Theophilus Naaké. Elfenreigen deutsche und nordische Märchen, by Marie Timme, an 1877 collection of Germanic-based fairytales, features the melancholy story of "The Fallen Bell." A nix, furious that he no longer receives human sacrifices, drowns a small girl and keeps her soul beneath a sunken bell. These examples point to an origin around Germany and the Czech Republic. They retain a creepy tone which "The Soul-Cages" lost. The villains are explicitly demonic, the trapped souls truly suffering. Meanwhile in "The Soul-Cages," the fisherman remains drinking buddies with the easily duped merman while freeing any souls he catches. Coomara isn’t even an evil being. By his own account, he is just trying to help the drowned souls, and this is supported by the fact that he never does the fisherman or his family any harm. The story is goofy rather than eerie, and the main takeaway is the Irish stereotypes. The tormented history of "The Soul-Cages" betrays the ease with which any folklorist could sneak in a story and claim it was traditional. Everyone was aware of this. Markey points out that Keightley himself highlighted at least two tales of suspicious origin in other collections. Even the Grimms, whom both Croker and Keightley idolized, hadn't really gotten their stories from the German peasant folk, but from middle-class readers of French fairytale collections. The Grimms also made major edits to polish the collection for a public audience. So, in summary:

If you believe Keightley's letter, "The Soul Cages" was not intended as a prank on Croker, or anything of that nature. He said Croker was fully aware of its nature and was the person who came up with the idea. At this point we will never know for sure whether that's true. However, Croker himself pointed out the similarities to the Grimms' story and printed the two tales in the same volume. Publishing your plagiarized work with the original for comparison seems phenomenally stupid. Keightley would probably love to inform us that Croker was exactly that stupid. I still don't know if Croker ever responded to the reveal of The Soul Cages' true origin. Whatever else occurred, I find it interesting that this story gave us the song "The Soul Cages" by Sting. Sources

2 Comments

In 1697, Charles Perrault published the story of "Cendrillon: ou la Petite Pantoufle de verre" (Cinderella, or the Little Glass Slipper). This is probably the most widespread version of Cinderella, thanks in large part to its adaptation by Walt Disney. I often see people on the Internet insist that "the original Cinderella wore gold slippers and had the stepsisters cut off their toes and get their eyes pecked out by birds!" But that was "Aschenputtel," the version from the Brothers Grimm. Perrault published his work 115 years before the Grimms did. It's impossible to identify an "original" version of Cinderella, but at least in terms of publication, the glass slipper came first.

But was it really a glass slipper? There is a persistent theory that the shoes were originally made of fur - which is about as far from glass as you can get! This theory may have originated with Honore de Balzac, in La Comédie humaine: Sur Catherine de Médicis, published between 1830 and 1842 and finalized in 1846. The word for glass, "verre," sounds the same as "vair" or squirrel fur. This fur was a luxury item which only the upper class was allowed to wear. Therefore, claimed Balzac, Cinderella's slipper was "no doubt" made of fur. Since then, quite a few authors have relied on this alternate origin for Cinderella's origins, usually in order to fit the story into a more "realistic" mold. It has also produced a persistent legend in the English-speaking world that Perrault used fur slippers and was mistranslated. Yes, glass shoes raise questions. How did she dance in them? How did she run in them? Wouldn't they have shattered? Wouldn't they have been super noisy? Fur slippers erase those questions entirely. But Cinderella stories regularly include things like dresses made of sunlight, moonlight and starlight. Forests grow of silver, gold and diamonds. Prisoners are confined atop glass mountains. In Perrault's version alone, mice are transformed into horses and pumpkins into carriages. Glass slippers should not be an issue. In fact, they fit perfectly well with the internal logic of the fairytale. As has been pointed out by others, the whole point of the slippers is that only Cinderella can wear them. Fur slippers are soft and yielding. Glass slippers are rigid and you can see clearly whether they fit a certain foot. Moving into symbolism: they are expensive, delicate, unique, magical. Cinderella must be light and delicate, too, in order to dance in them. They are a contradiction in terms (of course it would be impossible for a woman to dance in glass shoes! That's the whole point!) and that's why they have captured so many imaginations. The fact is that Perrault wrote about "pantoufles de verre," glass slippers. He used those words multiple times. There is no question that he was talking about glass. No one mistranslated Perrault. However, did he misunderstand an oral tale which mentioned slippers of vair? It's important to note that "vair" was popular in the Middle Ages. By Perrault's time, this medieval word was long out of use! It is still possible that Perrault could have heard a version with vair slippers - but is it probable? What stories might Perrault have heard? In her extensive work on Cinderella, Marian Roalfe Cox found only six versions with glass shoes. She found many that were not described, many that were small or tiny, and many that were silver, silk, covered in jewels or pearls, or embroidered with gold. A Venetian story had diamond shoes, and an Irish tale had blue glass shoes. Cox believed that other versions with glass slippers were based on Perrault's Cendrillon. Paul Delarue, on the other hand, thought these versions were too far away in origin, which would make them independent sources - which means Perrault could have drawn on an older tradition of Cinderella in glass shoes. Gold shoes are perhaps significant. Ye Xian or Yeh-hsien, a Chinese tale, was first published about 850, and its heroine's shoes are gold. Centuries later, the Grimms' Aschenputtel takes off her heavy wooden clogs to wear slippers “embroidered with silk and silver,” but her final slippers - the ones which identify her - are simply “pure gold.” It’s not clear whether this means gold fabric or solid metal. As for other early Cinderellas: Madame D'Aulnoy published her story "Finette Cendron" (Cunning Cinders) in 1697, the same year as Perrault's Cendrillon. Her heroine wears red velvet slippers braided with pearls. Realistic enough. The Pentamerone (1634) has "La Gatta Cenerenterola" (Cat Cinderella). It's not said what the heroine's shoes are made of, but she does ride in a golden coach. Note that shoes are not always the object that identifies the heroine. In many tales, it's a ring - something likely to be made of gold or studded with gems. What if, at some pivotal point, far back in history, a storyteller combined the tiny shoe and the golden ring into a single object? On the other hand, I have never found a Cinderella who wears fur slippers to a ball. Fur clothing appears in Cinderella stories such as "All-Kinds-of-Fur," but it's used as a hideous disguise. Rebecca-Anne do Rozario points out that "Finette Cendron" (which, again, came out the same year as Perrault's "Cendrillon") has Finette instruct an ogress to cast off her unfashionable bear-pelts. Fur clothing was not a symbol of wealth or status, but of wildness and ugliness. Glass slippers were most likely Perrault's own invention dating from when he retold his folktales in literary format. No translation error, no misheard "vair" - just a really good idea and his own storytelling touch. If anything, he probably heard stories where the slippers were made of gold, or where their material was not mentioned. It was only later writers like Honore de Balzac who added the confusion of the squirrel-fur slippers, and folklorists and linguists have been arguing against it ever since. James Planché wrote in 1858, "I thank the stars that I have not been able to discover any foundation for this alarming report." That was twelve years after Balzac's book was officially completed. Heidi Anne Heiner at SurLaLune points out that the vair slipper theory dismisses Perrault's "adept literacy," and "negates [his] interest in the fantastic and magical, discounting his brilliant creativity." Unfortunately, as shown by Alan Dundes, the vair/verre theory made it into influential sources such as the Encyclopaedia Britannica, and thus has been fed as fact to successive generations of readers. Who's going to question the Encyclopaedia Britannica? And so this rumor remains persistent. As a final bit of trivia: there is one mention of glass shoes in the Brothers Grimm's tales. “Okerlo” appeared only in their 1812 manuscript and was quickly removed. (This is perhaps because it is clearly a retelling of a French literary tale, “The Bee and the Orange Tree.” Not unusual for the Grimms, but in this case it may have been just too blatant.) In the final lines, the narrator is asked what they wore to a wedding. They describe ridiculous clothes, with hair made of butter that melts, a dress of cobwebs that tears, and finally: “My slippers were made of glass, and as I stepped on a stone, they broke in two.” Here, the destruction of the fairytale clothing points out how impossible the magical tale is, and signals the end of the story and a return to reality. Sources

Have you ever wondered how you say "Prince Charming" in other languages? In several Romance languages, the term translates to "The Blue Prince" and is a common term for the perfect man. There's the "príncipe azul" (Spanish), "príncep blau" (Catalan), "principe azzurro" (Italian), and "prince bleu" (French). In all cases, the idea translates to what an English-speaker would call a Prince Charming or a knight in shining armor. Variants of this term go back at least to the 18th century.

Zadig ou la Destinée by Voltaire (1747) features a joust in which the hero Zadig wears white armor and defeats a man in blue armor, who is referred to briefly as "le prince bleu." This is only a passing line, but one wonders if it was a reference to a well-known phrase. Sur la scène et dans la salle. Miroir des théâtres de Paris (1854) describes a play featuring the role of "prince Azur" (p. 46). The Revue de France in 1879 mentions "le prince bleu des contes de fées." Victor Hugo's Les quatre vents de l'esprit (1881) has "le prince Azur" (p. 252). "Le prince Bleu" and "roi Charmant" (King Charming) both get a mention in Jules Claretie's Noris: mœurs du jour (1883, p. 37). In Contes populaires de Basse-Bretagne by Francois-Marie Luzel (1887), a character in the tale of "Le Prix des Belles Pommes" is called Le Prince-Bleu. He is the hero's strongest rival for the princess's hand, but receives a dismal fate while the despised hero triumphs. By 1893, La Union literaria defines "Príncipe Azul" as a character "de una mitologia fastidiosa ser inverosimil y aereo" (of an annoying mythology, improbable and airy). This isn't even close to an exhaustive list. Oddly enough, in quite a few of these examples, the blue prince gets set up as the classic knight in shining armor, but is either disparaged as a foolish idea by the narrator or given a comeuppance by the story. So why "blue"? Apparently there has been some speculation that King Vittorio Emanuele III of Italy was the original for the Blue Prince. Blue was the traditional color of his family, the House of Savoy. An article by Paolo Zollo was titled "Che il Principe Azzurro sia stato Vittorio Emanuele?" (Was the Blue Prince Vittorio Emanuele?) in Messaggero veneto (1982). A connection had been drawn previously by Giovanni Artieri, who described Vittorio's wife Elena as "Cenerentola" (Cinderella) and Vittorio as "un Principe Azzurro, azzurro Savoja" - "a Blue Prince, Savoyan blue." (Il tempo della Regina, 1950, p.52). Unfortunately for this theory, Vittorio and his wedding (which seems to have inspired the comparison) are a bit late. One possibility is that "the blue prince" comes from the idea of blue-blooded royals. Blue-blooded has long been a way to refer to the nobility. The nickname is derived from the Spanish "sangre azul" dating at least to 1778. It was theoretically inspired by the nobility, with their fair skin that showed off blue veins. Or the prince might literally be wearing blue. Blue pigment was expensive in the past and often marked the clothing of the nobility. The Oxford English Dictionary lists a number of uses of the term "royal blue," including an advertisement in the 1782 Morning Herald & Daily Advertiser: "Among other colours are the royal blue, the green, pink, the Emperor's eye, straw, &c." Similarly, there is a 1787 reference to a sky "of the deepest royal blue." There are a multitude of possible explanations for the "blue prince" term. According to this forum thread, one Hungarian term for a Prince Charming is "kék szemű herceg," or the blue-eyed prince. So depending on how you look at it, the term could be a reference to blue blood, blue clothing, blue eyes, or something else entirely. Whichever the case, those three things all accentuate the relevant traits of the archetypal fairytale prince. He's royal, rich, and good-looking. All the same, it seems writers had tired of this ideal even in the 19th century, disparaging the character as unrealistic or showing a less promising hero who defeats him. The Scottish tale of Childe Rowland was first published by Robert Jamieson in 1814. This tale follows the children of King Arthur - specifically, a son called Child Roland and a daughter called Burd Ellen. (Child and Burd are noble titles for a knight and lady.) The King of Elfland steals Burd Ellen, and one by one her brothers seek her. The two oldest never return from Elfland. Roland, the youngest, goes to Merlin for advice, then fights his way into the otherworld with his trusty claymore. There he finds his sister, who offers him food, but he remembers Merlin's wisdom and refuses to eat. The elf king arrives, chanting, "With a fi, fi, fo, and fum! I smell the blood of a Christian man!" Roland fights him to a standstill and forces him to resurrect his two brothers, killed trying to save Ellen. The elf king anoints them with red liquid from a crystal phial and brings them back to life. With that, the four siblings proceed home.

Jamieson heard the story from a tailor at age seven or eight, and reconstructed it years later. He mentions that he left out some details because he wasn't sure of his memory. He added in the names of Arthur, Guinevere, Excalibur, and the location of Carlisle, based on the fact that Merlin appeared in the story. Although the story as Jamieson tells it can only be dated to the early 1800s, there is evidence of the story being older. For one thing, Rowland's name appears in Shakespeare's King Lear (1606). The line is spoken by Edgar, posing as a mad fool who rambles only nonsense. Child Rowland to the dark tower came, His word was still,--Fie, foh, and fum, I smell the blood of a British man. This is echoed in Jamieson's version with the "fi, fi, fo, fum" chant; Jamieson said that it was one of his most enduring memories from hearing the tale for the first time. Later, the folktale collector Joseph Jacobs published a retelling which called the King of Elfland's dwelling the "Dark Tower," drawing on the King Lear verse. Previously, other readers believed that the nonsense verse might be a mix of references - for instance, "Childe Roland" might be from the eleventh-century French poem Song of Roland, and the "fie, foh and fum" from "Jack the Giant-killer." Jamieson presented an alternative: the Scottish story of Childe Roland. This all began in his 1806 collection Popular Ballads and Songs. In the first volume, he described three Danish ballads about a character named Child Roland. He gave the first of these ballads in the second volume of Popular Ballads, and the second two in Illustrations of Northern Antiquities, along with his retelling of the English version. From the very beginning, Jamieson was focused on that one line in Shakespeare - more on that later. The Danish ballads came from the 1695 work Kaempe Viser or Kæmpevise. It's not clear whether any of them appeared in the original, shorter edition of 1591, and I have not been able to locate a copy of either, so I have to base my knowledge on Jamieson's translation. In the first, the main characters are an unnamed youth and Svané, the children of Lady Hillers of Denmark. The second has Child Roland and Proud Eline (no parentage given), and the third has Child Aller and Proud Eline (children of the king of Iceland). The second version is the longest and most dramatic, and uses nearly the same names as Jamieson's Scottish tale. In all three ballads, the villain is a monstrous giant or merman known as Rosmer Hafmand, who dwells in a castle beneath the sea. Roland (or Aller) sets sail in search of his sister and reaches Rosmer's castle after his ship sinks. He enters the castle as a spy and lives there for some time. In the second version, Roland and Eline begin an incestuous relationship and Eline becomes pregnant. In these ballads, there is no daring battle between Roland and his sister's abductor; instead, he pretends he's leaving, packs his sister in a chest, and asks Rosmer to carry it for him. He rescues the captured maiden through trickery instead of combat. Jamieson and others argued that Childe Rowland was an ancient English tale which spread to Denmark. This was Jamieson's pet theory which he was pushing very hard. Besides King Lear, there are a couple of older works with plots similar to "Childe Rowland." In The Old Wives' Tale, a 1595 play by George Peele, there are multiple plot threads and fairytale references. The most relevant plot thread deals with two princes searching for their sister, stolen away to the sorcerer Sacrapant's castle. (All of the names are from the Orlando Furioso). They are aided by an old man (similar to Merlin) but eventually all three siblings are rescued by another party. Similarly, in the masque Comus, first presented in 1634, the necromancer Comus steals away an unnamed lady to his palace, where he tries to entice her to eat the food he offers. She holds out until her brothers arrive to rescue her. Even then, the lady can only be freed by touching her lips and fingers with a magic liquid, similar to the ointment which resurrects Roland's brothers. The similarities are clear and have been pointed out by various writers. So we know that:

Some writers have tried to strengthen the tale's ties to King Arthur, but I think this is a mistake. Roger Sherman Loomis, in Celtic Myth and Arthurian Romance, suggests that Child Rowland "seems to go back through an English ballad to an Arthurian romance" and is ultimately derived from the 8th- or 9th-century Irish tale of Blathnat. Blathnat, the lover of Cuchulainn, is abducted by a giant named Curoi. At least two Arthurian romances include this sequence of events: De Ortu Waluuanii (The Rise of Gawain), with the villain as the dwarf king Milocrates, and The Vulgate Lancelot with the villain being the giant Carado. Although the characters vary, the story remains the same: a maiden is abducted by a being who can only be slain by one weapon. Her lover sneaks into the being's fortress to rescue her. The damsel steals the weapon and gives it to her lover, who beheads the villain. This is the family of tales to which Loomis tried to tie Childe Rowland. However, the only thing they really share is the motif of the abducted maiden's rescue. That motif is incredibly widespread through many different tale types. I would say Childe Rowland bears more resemblance to "Sir Orfeo" (a middle English retelling of the myth of Orpheus) than it does to Blathnat's story. In addition, Loomis' theory ignores that "Childe Rowland" is a reconstruction and that Arthur and Guinevere were added in based on a single mention of Merlin. BIBLIOGRAPHY

Santa Claus isn't the only Christmas character who brings gifts. There's a wide number of different gift-bringers in cultures across the world, and a significant portion of them are ladies.

As far as I can find out, the first mentions of a Mrs. Claus go back to the mid-18th century. In the 1849 short story The Christmas Legend by James Rees a couple disguises themselves as "old Santa Claus and his wife." Then in 1851, in The Yale Literary Magazine, one author remarked that Santa "we should think, had Mrs. Santa Claus to help him." From there, the floodgates opened. Mrs. Claus appeared all over the place in short stories and poems, helping Santa Claus with his work. Some of her other names are Mother Christmas (English), Weihnachtsfrau, Nicolaaswijf (German), Joulumuori, Kerstwrouvtje, Kerstomaatje (Finnish), Bayan Noel (Turkish), or La Mère Noël (French). She never really got a name beyond "Santa's wife" in any of these languages - although in a March 1881 issue of Harper's New Monthly Magazine, we learn that among Dutch immigrants, St. NIcholas was "sometimes accompanied by his good natured vrouw, Molly Grietje." I have yet to find other textual support for this tradition, and this may not be a factual account of Dutch settlers. In other countries, St. Nicholas was occasionally accompanied by a female counterpart, like the Niglofrau (Nicholas wife) in Upper Austria and the Nikoloweibl in Bavaria. (The Krampus and the Old, Dark Christmas). In Tirol, there was the Klasa (a feminine variant of Klaus), a well-dressed woman who went in St. Nicholas's processions and distributed gifts from her basket. This was recorded in 1875 in Tagespost Graz. A Friesian nursery rhyme, published in Dutch in 1892, implied the existence of a whole Santa family, with Sintele Zij as the wife. But female gift-bringers of Christmas go back further. In some cases, a female saint appeared in place of Saint Nicholas. One of the most famous was Saint Lucy, whose feast day falls on December 13. In Sweden, there were Lucia processions where she led a troop of children dressed in white, including the stjärngossar or star boys. In the Czechlands, on December 4 - the eve of St. Barbara's Day - women would dress as the Barborky, or Barbaras, in white dresses with veiled faces. They carried baskets of fruit and sweets for the good children, and brooms to threaten bad children. (Czech Traditions and Folklore) (Prague City Line) In some Czech families that immigrated to America, Matíčka or the Blessed Mother would leave treats in children's shoes on the Feast of the Immaculate Conception (December 8). (Christmas in Texas) In a lot of Christian countries, people cut out the middleman and had Baby Jesus bring gifts. However, somehow this got turned around. The German Christkind became America's Kris Kringle, alias of Santa Claus - and in Germany, became a beautiful young girl like Lucia, dressed in gold with a crown on her head. The same thing happened to the Wienechts-Chindli in Switzerland and the Kinken Jes in Sweden. There was also the Wends' veiled Dźěćetko (Little Child) or Bože dźěćo (God’s Child). In other countries, the gift-bringer was an elderly crone like the Befana (Italy), Babushka (Russia), or la Vieja Belén (Dominican Republic). Searching for the Child Jesus, she gives gifts to the children she meets along the way. These Christian characters replaced older figures from older winter festivals. For instance, the Christian martyr Lucy stepped into the shoes of an older figure, the terrifying Lussi. These gift-bringers varied from beautiful, shining young women to monstrous hags. They often made their visits between Christmas and the feast of Epiphany. Perchta, Frau Holle, Hulda, Frau Gode, Frau Lutz, Bertha, Butzenbercht, or Eisenberta (Iron Berta) were some of the many names used for a Germanic goddess figure. Traveling with her assistants, she would bless the people who welcomed her into their homes in the twelve days between Christmas and the feast of Epiphany. She passed judgement on those whose work didn't measure up. According to the Thesaurus pauperum (1486), between Christmas and Epiphany, people left out food and drink at night for a woman named Lady Abundia, Domine Habundie, or Satia. Dame Abonde was apparently still around in the 19th century as a French gift-bringer of New Year, according to Brewer's Dictionary of Phrase and Fable (1898). Names like Frau Faste and Quatemberca referred to the Ember Days. In some cases, the Perchta character was a hideous monster well-known for her one goose foot and her long beak-like nose - earning her the Austrian name Schnabelpercht or Beak Perchta. Martin Luther referenced "Dame Hulda with the snout." She was also known as the Spinnsteubenfrau, or Spinning Room Lady. In Franche-Comte, Tante Arie was a gift-bringer but also a frightening figure with iron teeth and goose feet. The chauchevielle (also a name for a bogey or a nightmare) and the trotte-vielle were terrifying figures active around the holly-jolliest of seasons. In Iceland, Gryla was a troll who ate bad children and in modern times gained an association with Christmas. In the 19th century, Jacob Brown wrote of his childhood in Maryland and the Christmas visitor known as Kriskinkle, Beltznickle or the Xmas woman. They were disguised and "generally wore a female garb - hence the name Christmas woman." (Brown's Miscellaneous Writings) On the softer side, there were beautiful White Lady types. La Dame de Noel showed up in Alsace. Anjanas, in Cantabria, were fairies of the mountain who would bring gifts on January 6 every four years (Manuel Llano, Mitos y leyendas de Cantabria). So before the beautiful Marys and Lucias, and before the old crones like La Befana, there were already lovely ladies and hideous hags going back to much older myths. These myths surrounded goddesses and demons who were celebrated around the winter solstice. Some of these names, like Bertha and Lucy, have names which intriguingly mean bright or light. St. Lucy, as already mentioned, has "star boys" for companions. In some areas of Poland, the gift bringer was not St. Nicholas, but the Gwiazdor (star man) and sometimes along with him, the Gwiazdka (star woman) or Piękna Pani (beautiful lady). (Star symbolism and Christmas gift-bringers from Polish folklore) Was this related to a celebration of the sun's return and the days growing longer after the winter solstice? More characters have been created during modern times. Mother Goody, Aunt Nancy or Mother New Year brings gifts for New Year’s in Canada. Snegurochka (Snow Girl) is the young female helper of Ded Moroz (Father Frost) in Russia. (Babica Zima, or Old Woman Winter, may also have been proposed as a gift-bringing figure.) In a funny twist, during World War II, women sometimes took up the whiskers and played Santa Claus. "Kristine Kringle! Sarah St. Nicholas! Susie Santa Claus!" one scandalized columnist called them. (Smithsonian) One wonders what that writer would have thought of the older tradition of otherworldly women who came at midwinter with gifts and punishments. Leaving out cookie and milk for Santa probably has its origins in the same tradition where people left out offerings for Lady Abundia. There's an interesting motif in folktales surrounding fairies' reaction to Christianity, and their hope for an afterlife. Norwegian folklorist Reidar Thoralf Christiansen categorized these as Type 5050, Fairies' Hope for Christian Salvation. You can find some of these tales at D. L. Ashliman's site. The story can vary widely, but generally - in tales collected from Sweden, Norway, and Ireland - a preacher tells the fairy that they will not receive God's salvation. The inconsolable fairy begins to weep and wail. However, in some versions, the preacher has a change of heart and gives them some hope.

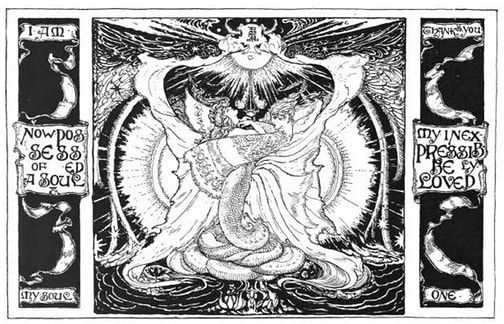

Some fairies try to enter the church via subterfuge, by switching out a human baby for a changeling. In a Swedish tale, the human mother learns the truth on the way to her son's baptism, when the infant boasts to the other fairies, "I am off to the church to become a Christian." The Asturian xanas were known to try the same trick, according to Mitología y brujería en Asturias by Ramón Baragaño (1983). This ties in with ideas of fairies' origins. In some stories, they are the spirits of the dead, particularly unbaptized children. The rusalka in Russian lore are the ghosts of drowned women. In another school of thought, fairies are fallen angels. In the Irish tale "The Blood of Adam," the fairies cannot be redeemed because they are not of the human race for whom Christ died. But in Norway, the story of "The Huldre Minister" goes in the exact opposite direction. A minister seeking to convert the fairies is surprised when one knows the Bible as well as he does. This one claims that the fairies are the descendants of Adam - by his first wife Lilith instead of Eve. Lilith was not involved in humanity's original sin, so they don't need to be redeemed at all. It seems like there's a particular theme of water spirits seeking redemption. The xanas live in rivers, and the fairy-salvation story is told of the Swedish Nack or Nickar, a water spirit. Even when they're not explicitly water fairies, they may appear by a river, as in one Irish story. The idea of water spirits' salvation really takes form in stories of mermaids who lack souls. This theme appeared in the work of Paracelsus, a Swiss alchemist. In his 16th-century work Liber de Nymphis, sylphis, pygmaeis et salamandris et de caeteris spiritibus, he described four types of elemental beings: undines (water), sylphs (air), gnomes (earth) and salamanders (fire). Despite their powers, they lack the eternal soul that humans possess. The only way for them to acquire a soul is to marry a human being. Any children of this union would be born with souls. According to Paracelsus, the most common marriages were of humans to undines - as with Melusine or the nymph bride of Peter von Stauffenberg. There are echoes of folklore here, but he's definitely creating his own mythology. In German, there's a word for marriage between a human and a supernatural being: Mahrtenehe. As pointed out by Claude Lecouteux, Paracelsus turns the Mahrtenehe motif on its head. In traditional lore, the supernatural being often leads the human to a new, eternal existence in another realm. In Roman myth, Cupid makes Psyche a goddess on Olympus, and in medieval legend, Sir Launfal's bride takes him away to Fairyland. Paracelsus, however, has the human guiding the elemental away from its heathen origins, to eternal life in Heaven. Paracelsus' influence continued in works like The Comte de Gabalis (1670). This widely read French novel revolved around a secret society of mystics. They abstained from marriage, hoping to offer their service as husbands to nymphs. It is currently considered a satire of occult philosophy, but was taken seriously through most of its history and inspired the use of Paracelsian elementals in other literature, like the poem The Rape of the Lock. This led to many works where humans fell in love with elemental beings. One example is the ballet "The Sylphide." Another is Friedrich de La Motte's famous 1811 novella, Undine, which concerns a water nymph marrying a human in order to gain a soul. If her husband is ever unfaithful, she will lose her soul again and he will die. It's basically an adaptation of "Peter von Stauffenberg" by way of Paracelsus. These stories about soul-marriage are literary tales. I can't think of any stories from oral folklore that include this theme, except that in the Orkney Islands, the Fin-Folk could retain their youthful beauty only if they married humans. Much like the fairies mentioned earlier, the Fin-Folk had an uneasy relationship with Christianity. They couldn't live where the Gospel was preached, hated the sight of crosses, and a man could escape them by repeating the name of God three times. (Scottish Antiquary, 1891) (Folklore mermaids can vary wildly from cross-fearing murderesses to the churchgoing Mermaid of Zennor.) There are stories like "The Peasant and the Waterman" from Germany and "Lidushka and the Water Demon's Wife" from Bohemia. In these tales, merfolk trap the souls of drowned victims underwater, but a visiting human opens the cages and frees them. Thomas Keightley suggested that this was inspired by older mythology of sea deities who took drowned souls to themselves. Undine's successor was Hans Christian Andersen's Little Mermaid (1836). Andersen didn't like Undine's ending, where the nymph depended on a human being for salvation, and had the Mermaid work her way to Heaven on her own merits. "The Little Mermaid" inspired countless variations of its own, such as Oscar Wilde's "The Fisherman and His Soul" (1891). Robert Buchanan also used the soul theme for the asrai in "The Changeling: A Legend of the Moonlight" (1875). Those last two toy with the inherent themes of the old folktale. "The Changeling" takes a dark, cynical view of humanity; the soulless nature spirits are far more virtuous than humans. "The Fisherman and his Soul," which deals with a human giving up his soul to be with his mermaid lover, celebrates love while raising questions about religion. In these stories, to be soulless is to be in a state of innocence rather than evil. So, to recap: there have always been legends of marriage of humans to gods or other powerful supernatural beings. As Christianity became established, authorities demonized the old pagan gods and spirits. They were recreated as evil beings that feared the church even if they wanted to enter it. Paracelsus put his own spin on the story: these creatures had a shot at redemption by marrying humans, in which case they could earn their own soul. This inspired the tale of Undine, which inspired The Little Mermaid. More recent reactions, if they address this, tend to question established Christian ideas about salvation and the soul. Sources

In Welsh legend, corgis were once the steeds of the fairy folk. You can still see the faint markings of the fairy saddles across the Pembroke Welsh Corgi's shoulders and back... or so I've heard. I found many books and websites which mentioned the "ancient legend," but none provided a source. Conversely, I could not find any books of Welsh legend that mentioned the corgi's enchanted origins. It's an orphaned fun fact.

Welsh Corgis have been around for a long time. They were bred as cattle dogs, whose small stature helped them avoid the cows' kicking hooves, but they worked with all sorts of livestock. In the 1920s, their name came into more widespread use and they were officially acknowledged as a breed. The English Kennel Club formally recognized the two Corgi breeds, Pembroke and Cardigan, as separate in 1934. There are many theories on where their name came from. One is that it is a compound meaning "dwarf dog": cor (dwarf) + ci (dog). Some modern sources connect this to the Little Folk. This debate is not new. The Dictionary of the Welsh Language by William Spurrell (1853) defined corgi as a "cur dog." The "cur dog" definition might have more historical support, going back as far as 1574 in William Salesbury’s Dictionary in Englyshe and Welshe. Here, cur would just be used in the sense of a dog of low breeding: a working dog as opposed to a lapdog. In A Dictionary of the Welsh Language (1893), Daniel Silvan Evans defended the "dwarf dog" definition, which is more widespread today. However, he was not using "dwarf" in the sense of fairy. He just meant it was a small dog. So when did the fairy saddle legend originate? The earliest source I can find is the poem "Corgi Fantasy" by Anne G. Biddlecombe of Dorset, England. She was one of the top Pembroke breeders of the 1940s and 1950s, and a founding member of the Welsh Corgi League in London, serving as their secretary for some time. She used the pedigree prefix Teekay, under which many of her dogs became show champions. The poem was first published in 1946 (in the first edition of the Welsh Corgi League Handbook?). Two children find some foxlike puppies out in the woods and take them home. Their father tells them that the dogs are a gift from the fairies, who ride them or use them to pull coaches and herd cows. He points out the image of the fairy saddles on the dogs' coats. This poem soon became popular and was reprinted in numerous magazines and books, crossing over from England to America. It featured at least twice in the American Kennel Gazette, in 1950 and 1956. The artist Tasha Tudor drew illustrations when it appeared in the Illustrated Study of the Pembroke Welsh Corgi Standard (1975). (Tudor was a well-known fan of Corgis. In the introduction to her 1971 picture book Corgiville Fair, she said, "They are enchanted. You need only to see them by moonlight to realize this.") Other modern corgi enthusiasts added their own twists with books, poems and stories like "The Fairy Saddle Legend" and "How the Corgi Lost his Tail." Many artists have turned their talents to drawing corgis with fairies. The stories mention the corgis serving as the fairies' battle steeds - a fantastic mental image. As an interesting sidenote, the Pembroke Welsh Corgi Club of America uses the acronym PWCCA. The pwca or pooka is a mischievous spirit in Welsh folklore. Pembrokes weren't the only ones with otherworldly connections. "Rhodd Glas: The Blue Gift," by Pam Brand, appeared in the 1996 handbook of the Cardigan Welsh Corgi Club of America. Brand described how the fairies created the first blue merle Cardigan corgi from a wildflower. Some even say that corgis were used in a war between the Tylwyth Teg and the Gwyllion, but this is hard to verify. In fact, these two fairy types may be the same thing, not separate tribes at all. The farthest I could trace that particular variation was the book Gods, ghosts and black dogs: The fascinating folklore and mythology of dogs, published in 2016. Later that same year, a Mental Floss article "The Ancient Connection Between Corgis and Fairies" used the story. You may notice that none of these sources are from fairytales or folklore collections. Instead, they're from articles on dog breeds. At this point, I have found no ancient tales of fairies riding any kind of dog. However, I have found a few Welsh legends of fairy steeds. In "The Tale of Elidorus," from Giraldus Cambrensis' account in 1191, the little people rode miniature horses perfectly adapted to their size. They had similarly tiny greyhounds. In Thomas Crofton Croker's Fairy Legends (1828), a woman from the Vale of Neath saw an army of fairies "mounted upon little white horses, not bigger than dogs." That's at least a small step closer to the corgi legend. Based on all this, I would guess that the legend of the corgi's fairy origins is new, not ancient. It's a modern folktale which grew naturally out of the subculture of corgi breeders and fans. The idea of the "saddle marks" took shape around the time the dog's characteristics were being formally defined. The "Corgi Fantasy" poem was published twelve years after the Pembroke breed was recognized. Other people came up with their own spins on the story, and it developed from there. I'm currently working on a timeline of the corgi legend's evolution. Many of these poems and stories were first printed in dog magazines and handbooks, which makes them difficult to track down. If you have any clues, please send them in! Sources

The asrai is a type of English water fairy. This species appears in a few fairytale collections and fantasy novels, but they were first popularized by Ruth Tongue's 1970 book, Forgotten Folk Tales of the English Counties.

Tongue has been described as problematic. Although she's obscure today, her work inspired later authors and has found its way into all sorts of media. She was an amazing storyteller, and she was writing down traditions that had never been recorded before. Here's the problematic part: she made them up. She often built upon scraps of genuine folklore, but the greater part of her work is original. So where does this leave the asrai? In the tale that Tongue recalled from Shropshire and Cheshire, Asrai are peaceful fairy folk. Living deep beneath lakes, they emerge to see the moonlight once every hundred years. They will die if they ever come near sunlight. One night, a fisherman out in his boat happens to catch an Asrai in his net. He is entranced by her beauty and decides to take her home, even though she weeps and protests in a strange language. He covers her with some wet rushes. In the process, she touches his hand, leaving it icy cold for the rest of his life. He rows back as quickly as he can and reaches the shore just as the sun rises. When he picks up the rushes, he finds that the Asrai has melted away to nothing. Okay, so first off, for this book, Tongue had lost most of her notes in fires or moves and had to recreate the stories from memory. Whoops. Still, she manages to give two versions of this story. The first comes from "the Whitchurch Collection (Shropshire)." I found one Whitchurch Collection at the Whitchurch Heritage Center, but it dates from 2008. There's no way to tell what collection Tongue meant or where it might be now - let alone what was in the collection. For the second version, which is exactly the same with some different wording, Tongue says "From the author’s recollections of an account in local papers published between 1875 and 1912.” That is thirty-seven years' worth of newspapers. THIRTY-SEVEN YEARS. To accompany the tale, she provides quite a few anecdotes - a Welsh maid who calls full moons "Asrai nights," and various people who avoid deep water because of asrais. Again, her attributions are fragmentary and vague. One says simply "Correspondence, 13 September 1965 (destroyed by fire)." Going through English and Welsh tales, I found several stories of captured mermaids, but nothing about water fairies that melt. One water creature in Shropshire lore is the monstrous Jenny Greenteeth, but she couldn't be more different from the asrai. (Edit to add: Tongue's tale feels closer to the widespread English and Welsh tales where men take lake-dwelling fairies as brides, only to break some taboo and cause their wives to return to the water forever. Still, it remains unsettlingly unique.) There are plenty of spelling variants: asrey, ashray, azurai, and more. I searched the English Dialect Dictionary, the Oxford English Dictionary, and several books of dialects. The only word I found that was even somewhat close is askal, a water animal or newt, also spelled asker or asgill. Incidentally, Tongue's notes mention a person who thought "asrai" was a term for a newt. As of writing this, I am stumped. Every modern mention of the asrai goes back to Tongue. I have found one person's account of asrai that predates her book - in the works of Robert Buchanan. Buchanan published his poem "The Asrai" in The Saint Pauls Magazine, April, 1872. The brief verses described an ethereal race called the Asrai, "pale, yet fair" immortal beings living in darkness before the creation of sunlight. They are innocent and gentle, lacking human passions and pleasures, but also human vices. In 1875, the author R. E. Francillon wrote to Buchanan and asked him to submit a poem for Francillon's novel Streaked with Gold. The novel was to be published anonymously in the special 1875 Christmas issue of The Gentleman's Magazine, although the authors' identities were an open secret. Buchanan responded with "The Changeling: A Legend of the Moonlight." This poem, included as Chapter VI, has nothing to do with the rest of the book. It begins with a few verses very similar to its predecessor, explaining the Asrai, who are "cold . . . as the pale moonbeam." After the arrival of the sun, "the pallid Asrai faded away," going almost extinct, with only a few surviving in mountains and lakes. In their place, humanity begins to thrive. One Asrai mother envies the humans and wishes that her baby could live as one of them and gain his own soul. She leaves her home beneath the lake that night and enters a human house, where a woman and her newborn have just died in childbirth. The Asrai's spell causes her baby to inhabit the dead child's body, making him the titular Changeling. He grows up as a mortal man, while his mother invisibly watches over him. However, the human world corrupts him and he becomes cruel, lustful and violent. He eventually repents. Now an old man, he is known as the Abbot Paul and lives in a monastery by the lake where he was born. One night, his mother rises from the water and calls him. He dies and leaves his mortal form behind, freeing his Asrai self, but he has earned a soul and must move on to the afterlife. Mother and son are separated forever. I have no resources on what inspired Buchanan, except for a later mention of the poem by R. E. Francillon. In their correspondence, Buchanan provided the only clue to his inspirations by mentioning "the Bala Lake Tradition." There are a few stories about Lake Bala or Llyn Tegid in Wales, although I'm not sure which Buchanan meant. There is supposed to be a sunken city beneath its waters, and you can sometimes hear sounds or see its lights deep within. "The Changeling" also includes familiar motifs like the water fairy who lacks a soul. Tongue's asrai have webbed hands and feet and green hair. They are the size of twelve-year-old children. Buchanan's Asrai are pale, dressed in snowy white. They are invisible to humans, and seem more like spirits than mermaids. They don't melt. However, both are associated with moonlight and cold, live underwater, and avoid sunlight. They're also both associated with Wales and the Welsh border. Tongue's friend, the famous folklorist K. M. Briggs, took Buchanan's poems as evidence of an older tradition. However, although some elements of his poetry were inspired by fairytales, I have found no evidence that Buchanan ever said the asrai themselves were from folklore. It even seems like he developed the asrai between the first and second poems, since they have more ties to folklore in "The Changeling." Some of Tongue's stories do have a basis in tradition, but here, it's unclear. Her sources are impossible to track down. She throws out a few names, a few hints at newspaper articles and collections, but on closer inspection, they melt away just like the asrai. It's very easy to imagine her reading a book of poems and later remembering a few romantic details: delicate water sprites, greedy humans, a tragic ending. The asrai's haunting story catches the imagination. Almost fifty years after the publication of Forgotten Folk Tales, it's continually told and retold by different authors. A 2009 family event in Shropshire had a storytime segment featuring "north Shropshire’s very own mermaids, the Azrai." The asrai may not have been part of folklore before Ruth Tongue. Still, they're definitely part of folklore now. Update 6/7/2020: A fun little note - although Buchanan remains the oldest and only source for asrai, I have discovered an older story with a plot similar to Tongue's asrai tale. This tale comes from France. La Dame de la Font-Chancela was an otherworldly woman who would appear on moonlit nights by a fountain called Chancela. A local lord, seeing her beauty, snatched her up and tried to ride away with her on his horse. Instantly, she vanished from his arms, leaving him with a frozen feeling that put a stop to any lovemaking for more than a year. (Laisnel de la Salle, Croyances et Legendes du Centre de la France, 1875, p. 118) Update 1/1/24: Hey! Since this blog post, my essay "Melting in the Daylight: The Asrai’s emergence in modern myth" has appeared in Shima Journal. Read that essay for additional research and better context on the asrai mythos, including some must-read quotes from Robert Williams Buchanan's co-writer. Sources

The yumboes are fairies from the folklore of the Wolof people in Senegal, West Africa, on the coast near Goree Island. Yumboes are two feet tall and colored silvery white from head to toe. They are believed to be the spirits of the dead, and attach themselves closely to human families.

They live underground, beneath hills called the Paps. There are many hills named Paps across the world, so-called because they resemble the shape of a woman's breast. I found mentions of some in Senegal, including the Deux Mamelles. Though the Yumboes have luxurious dwellings where they invisibly host amazing feasts, they eat by stealing human food and carrying it off in calabashes. At least they catch their own fish. Yumboes appear occasionally in fiction, including the extended Harry Potter universe. In many ways, they're very similar to European fairies. The oldest mention I can find of them is Thomas Keightley's Fairy Mythology in 1828. All other descriptions of yumboes seem to be taken directly from Keightley's. It bears mentioning that Keightley, a pioneer in the folklore field, was Irish. At least to my knowledge, he never studied African cultures in-depth. Most of the fairies in The Fairy Mythology are European, with Africa, Asia and the Middle East stuffed in at the end. His source for yumboes is "a young lady, who spent several years of her childhood at Goree" and who herself heard the story from her Wolof maid. This means that yumboes as we know them are from a third-hand account. So I went looking for supporting evidence or any stories that might conceivably be about yumboe-like creatures. Unfortunately, much like my venture with pillywiggins (here and here), when I tried to find mentions of yumboes in Wolof folklore, I came up empty-handed. I couldn't even find mentions of the word in dictionaries. Quite a few sites claim that yumboe is a word from Lebou, a language closely related to Wolof, but provide no sources. A Tumblr post said that the Wolof word "Yomba" means pumpkin, which checks out. The writer draws a connection between "yomba" and the yumboes' love for stealing humans' food. But that still leaves us with no dictionary mention of yumboes. I also found the word yomba defined as "cheap." Incidentally, this post also pointed me towards a book of African-American tales, specifically "Mom Bett and the Little Ones A-Glowing" in Her Stories by Virginia Hamilton. The tale deals with tiny, glowing fairies who dance around a woman's garden. However, Hamilton comments, "Tales of fairies are few and mostly fragmentary in black folklore. This tale by the author is based on sparse evidence. The African American spirit world is one usually to be feared, and it deals mainly with witches, devils, boo hags, and ghosts." That's not particularly encouraging. What about the yumboes' other name, "bakhna rakhna" or the good people? Keightley seizes on this as a parallel to the Good Folk of European lore. I did find "baax" or "baah na" as Wolof words meaning good, which is close enough to "bakhna." However, I have not yet had luck with rakhna. Taking another tactic, there are plenty of stories of spirit lore in Senegal. There are the jinné, derived from the Arabic jinn. People of Wolof and Lebou ancestry have a tradition of protective ancestor spirits, the "rab," or evil beings, "doma." Closer to the "little people" archetype is the konderong or kondorong. Like most elves and dwarves of Africa, the konderong are no more than two feet tall, with feet turned backwards. Their beards are incredibly long, and they often wrap them around their bodies to serve as clothes. According to David Ames, they can be rascally or dangerous, and serve as guardians of the wild animals. According to other authors, the kondorong might be known to cut off cows' tails or to be great wrestlers. One oral tale is called "Hyena Wrestles a Konderong." According to Emil Anthony Magel, the konderongs' beards are white. A two-foot-tall creature wrapped in white hair sounds somewhat like the little white yumboes. But as I kept researching, I thought that maybe yumboes could be related to the jumbee or jumbie. The jumbie is a terrifying figure, a kind of demon in Caribbean countries among people of African descent. It may be linguistically related to Bantu "zombie," Kongo "zumbi" (fetish), or Kimbundu "nzambi" (god). That put me on a trail I could follow. The Kongo word "vumbi", according to King Leopold's Ghost by Adam Hochschild (1998), refers to "ancestral ghosts" who were white in color, for their "skin changed to the color of chalk when [they] passed into the land of the dead." And in Jamaica, "duppies" appear as ghosts, malevolent monsters, or - sometimes - fairylike little people, "white, with big heads and big eyes." They live in the branches of silk cotton trees, love singing, and have their own society with a king and queen. People leave out water or small pumpkins as offerings for them (Leach 1961). Yumboes come from West Africa. Zombi/zumbi-type terms are spread over West and Central Africa and the Caribbean. Which raises the question... could yumboes be related to zombies? PART 2: Yumboes and African Ghost Lore Resources

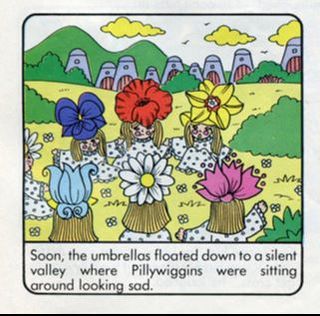

A while back, I set out to investigate pillywiggins - an obscure type of fairy that was oddly lacking in source material. After months of searching through bibliographies and ordering books through Interlibrary Loan, I gave up. I was at a dead end. I published my blog post and let it be.

Now I'm coming back to pillywiggins again. Bunny wrote in to say: “My late grandmother, originally from Wimborne, Dorset, would bemoan those pesky Pillywiggins whenever something went missing or awry.” (Thanks, Bunny!) Another thing I found, but that I didn't fully break down in the original post, was a My Little Pony comic. Evidently, the UK comic took "story requests;" the story "Pinwheel and the Pillywiggins," published May 1986, was requested for Wayne and Claire Cookson of Hanham, Bristol. The pillywiggins are never explained. They appear as small women with flowers on their heads (and no wings). That lack of explanation indicates that the author expected people to already understand what these creatures were. At the very least, Wayne and Claire knew what they were. This is also one of the earliest sources I have for pillywiggins, which makes it a vital piece of evidence. More recently, I bought a copy of Dark Dorset Fairies by Robert J. Newland (2006). Newland describes pillywiggins as small flower fairies with golden hair and blue wings. Despite their pretty appearance, they can be mischievous and untrustworthy. (There's no resemblance here to Dubois' insect fairies or McCoy's Queen Ariel! But it does tie in with pillywiggins being pesky troublemakers...) In one tale, a woman finds a group of tiny pillywiggins dancing upon her newly baked cake. When she tries to speak to them, they disappear into mist. (Compare Keightley, The Fairy Mythology, p.305: "as for the adjoining Somerset, all we have to say is, that a good woman from that county, with whom we were acquainted, used, when making a cake, always to draw a cross upon it. This, she said, was in order to prevent the Vairies [Fairies] from dancing on it. . . . if a new-made cake be not duly crossed, they imprint on it in their capers the marks of their heels.") In another tale, the "vearies in the honeyzuck" (vearies being a Dorset term for fairies) give gold to a pair of children, but the gold disappears as soon as the children tell how they got it. In the third story, we learn that Pillywiggins love hawthorn trees and will protect them by pinching encroachers or tangling their hair into fairy-locks. Two girls who fall asleep under a hawthorn tree wake up to find that the fairies have knotted their hair so badly that it must be cut off. The concept of fairy-locks or elflocks goes back at least to the 1590s with Romeo and Juliet. Hawthorn trees are often liminal places where humans and faeries can interact, as in the tale of Thomas the Rhymer. Newland's story takes place at May Day, a time during which the hawthorn would be blooming. In a final note, pillywiggins like to ring bluebells, and the chime of a bluebell - or fairy's death bells - is an omen of doom. In other recorded folklore, bluebells or harebells (which were often confused) were also known as witch's bells, Devil's bells, dead men's bells, or fairies' thimbles. (See this blog post at Hypnogoria.) As for an analysis of these stories: Many of the elements here, such as the fairy gold, are familiar. The cake story is one I recognize from an older source. However, I've never seen them associated with pillywiggins before. Newland's pillywiggins love honeysuckle, hawthorn, and bluebells. Each of these plants appeared in the Folklore Society's "Survey of Unlucky Plants," and were said to bring ill fortune if taken inside a house. In addition, hawthorn and bluebells have well-known connections in folklore to fairies. The word pillywiggin is mainly used in narration. At one point when it would be natural for a character to say the word "pillywiggin," she instead says "vearies." The impression I got was that the word pillywiggin was being applied to various stories of tiny plant-loving fairies, and may not originally have been associated with these tales. Some of the stories throw in names, locations, or ballpark dates, but there are no sources. There's nothing to indicate who told the story, or where or when it was told. The blue wings are a modern touch. Ancient fairies are not winged. I want to note that pillywiggin does hearken back to other words, such as pigwiggen or pigwidgeon for a tiny being. There is also piggy-whidden, a runt piglet. (Specimens of Cornish Provincial Dialect). Pirlie-winkie and peerie-winkie are words for the little finger, and peerie-weerie-winkie for something excessively small. (Transactions of the Philological Society) I'm still looking for more information, so if you've heard something about pillywiggins that I haven't mentioned, let me know! Part 1: What are Pillywiggins? Part 3: Pillywiggins in Pop Culture Part 4: Pillywiggins, Etymology, and... Knitting? Part 5: Diamonds and Opals: Two Romances Featuring Pillywiggins Part 6: Pillywiggins: An Amended Theory |

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed