|

Where did we get the idea of faeries in Summer and Winter Courts - or courts themed around all four seasons? Why does this appear so much in current fantasy novels? And what do they have to do with the Seelie and Unseelie Courts?

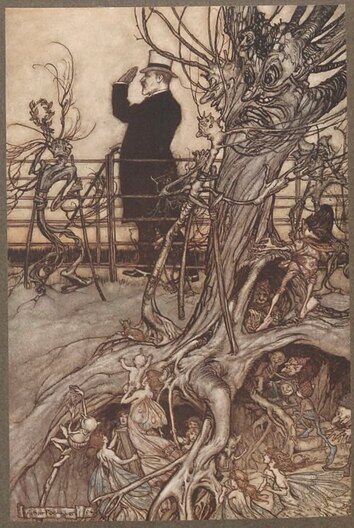

There are many legends of weather or seasonal spirits. Winter in particular has plenty of personifications. But these beings weren't necessarily fairies, and fairies weren't divided by seasons. If you go back to Shakespeare, Titania and Oberon were rulers over all the seasons. When did it get split up? This may have been a product of the Victorian era. Toned down for children, fairies became toothless things made primarily for education and edification. They were closely associated with nature and thus the seasons. There was some blurring of lines; this wasn't actually meant to promote genuine fairy belief, and often the "fairies" were poetic representations of insects, birds or plants. This was, after all, a way to educate kids on nature. In Victorian children's literature, fairies were responsible for painting the flowers, decorating the autumn leaves, or bringing snowflakes - and unlike Shakespeare, there were separate kingdoms. Fairies of spring, summer, autumn and winter worked in exclusive groups. In some books, they had their own monarchs, or there might be rivalries between groups. The Grand Christmas Pantomime Entitled Gosling the Great (1860) featured a fairy queen of spring named Azurina. "The Fairies of the Earth, and Their Hiding Places," by Lizzie Beach (1870) explained all of nature in fairy terms; Jack Frost was the king of the autumn and winter fairies. In the Libretto of the Fairy Operetta of the Naiad Queen (1872), the queens of each season are mentioned alongside queens of the fairies, sprites and flowers. Margaret T. Canby, in Birdie and his Fairie Friends (1873), included a story called "The Frost Fairies" in which Jack Frost is king over the fairies of winter. The trope of the seasonal fairy continued strong into the 20th century and continues to be popular. Julie Kagawa's Iron Fey series (beginning 2010) for one, features courts of Summer and Winter, while Disney's Tinker Bell animated movies (beginning 2008) put major emphasis on the fairies causing the seasons. But there's another factor that I believe is important here: The Oak King and the Holly King As mentioned, there are many myths to explain seasonal changes. Persephone is a classic seasonal myth. In Orcadian legend there is a constant struggle between the benevolent Sea Mither (Mother) and the evil storm spirit Teran who fight every spring and autumn. In Germany, Mother Holle was an legendary figure who created snow by shaking out her pillows. There were also holiday traditions where a person dressed as Summer defeated another dressed as Winter. In other cases, effigies were torn apart or thrown into the stream to celebrate the end of Winter. Robert Graves, in The White Goddess (1948), took influence from these rituals when he defined the Oak and Holly Kings. These were two gods who battled every year over a maiden representing Spring or fertility. The Oak King ruled during summer, but the Holly King defeated him and took over every winter. The yearly cycle goes on forever. Graves held that this was an actual myth that survived in multiple legends, and he had plenty of examples (Sir Gawaine and the Green Knight, for instance). In any story, if there are two men who fight (and particularly if there is a lady involved who can be connected to the Spring season), then there's your Oak and Holly King. It's very convenient. In fact, the Oak and Holly Kings are Graves' original creation, extrapolating from many different myths and the work of James Frazer. However, his work had a huge influence on modern paganism. For instance, Edain McCoy's popular 1994 book A Witch's Guide to Faery Folk is packed full of seasonal fairies as well as Gravesian mythology. Conclusion: Modern Times So in the twentieth century, you have a strong literary tradition of pretty little fairies being responsible for every change in season. And in addition to old myths of seasonal changes, you also have a newly popular neopagan theme of an unending power struggle between kings of Summer and Winter. However, what really tipped the scales was Jim Butcher's bestselling fantasy series: The Dresden Files. The 2002 novel Summer Knight introduced the fairy rulers. Butcher had the idea of conflating the seasons with the idea of the Seelie and Unseelie Courts - a concept from late Scottish folklore, which I examined recently on this blog. Thus, his fairies are split into two factions: the Seelie (or Summer) fae, ruled by Titania, and the Unseelie (or Winter) fae, ruled by Mab. Since the publication of this book, Butcher's system has grown huge in fairy fantasy - Titania and Mab as opposing seasonal queens, the seasons divided into Seelie and Unseelie, etc. Many authors seem to have lifted it wholesale straight from Butcher. And if Summer and Winter are courts, it seems reasonable enough that Spring and Autumn might also be courts, or that there might be other themed groups. Sarah J. Maas' series Court of Thorns and Roses has seven themed fairy courts (all four seasons, plus dawn, day and night). It is true that the Seelie Court is an old idea, as are good and evil fae, and fairies or other beings who influence the seasons. But originally, Seelie and Unseelie had nothing to do with the seasons. Thanks to popular literature, Jim Butcher's worldbuilding has grown popular enough to sometimes be confused for an old tradition. Other Blog Posts

2 Comments

What’s the deal with Kensington Gardens and fairies?

Kensington Gardens in London were originally part of a hunting ground created by Henry VIII. In the early 1700s, Henry Wise (Royal Gardener under Queen Anne and later King George I) made numerous adaptations including turning a gravel pit into a sunken Dutch garden. Queen Caroline ordered additional redesigns in 1728. In the 19th century, the Gardens transitioned from the royal family's private gardens to a popular public park and a place for families with children to walk or play. Over the years, the gardens have gained associations with fairies in literature. This can be traced to the 18th century, when Thomas Tickell (1685-1740) wrote the 1722 poem "Kensington Garden," a mock-epic starring flower fairies and the classical Roman pantheon, which gave the location a mythical origin. The basic plot is that the fairies once lived in that location, until King Oberon's daughter Kenna fell in love with a mortal changeling boy named Albion. This, naturally, led to war. Albion was killed, and while the fairies scattered across the realm in the brutal aftermath of the war, Kenna remained to mourn over his tomb. She eventually instilled royalty and architects with the inspiration for Kensington Palace's garden. Thus, the garden is based directly on the fairy kingdom that once stood there, and the name "Kensington" is derived from the fairy princess Kenna. "Kensington Garden" was evidently influenced by Alexander Pope's Rape of the Lock (also known as the first poem to give fairies wings). Both are mock epics imitating Paradise Lost, but with overwrought adventures of comically tiny fairies. Tickell's fairies are larger than Pope's, though, standing about ten inches tall. (Tickell and Pope were familiar with each other; both produced translations of the Iliad in 1715, and this caused a clash as Pope suspected Tickell of trying to undermine him.) Note that the title of the poem is "Garden," not "Gardens"; the modern Kensington Gardens were yet to begin construction. The poem was specifically focused on Henry Wise's sunken garden, explaining how that exact spot once held the "proud Palace of the Elfin King." Despite the faint note of absurdity in the tiny flower sprites, Tickell was working to create a mythical origin for Britain and its notable sites. Tickell's Albion is the son of a faux-mythical English king, also named Albion, who was the son of Neptune. Albion, senior, appeared in Holinshed's Chronicles in the 16th century, and in the fantasy works of Edmund Spenser and Michael Drayton. Tickell fashioned a story in which "the myths of rural and royal Kensington united" (Feldman, Routledge Revivals, 15). Inspired by the artistic renovations of the palace garden, he created a mythical prince from the dawn of England, whose fairy lover still watched over the modern royal family's home. He wanted to build a mythology showing the British royals' ancient pedigree. It was all part of England's grand heritage, leading back to classical Greece and Rome. Kenna resembles a patron goddess, but you can also see in her an idea of past English monarchs who might not have had children of their own, but whose influence was still felt. Tickell's influence shows in other works in the years following. James Elphinston's Education, in Four Books (1763) created a verse description ostensibly of education in general. When he got to the subject of Kensington House (a boys' school which he ran from 1756 to 1776), he described the location in grandiose terms as "Kenna's town... where elfin tribes were oft... seen". (p. 129) The description of the town echoes Tickell's poetry. Thomas Hull (1728–1808) wrote a masque called "The Fairy Favour" in 1766. It ran in 1767 as the scheduled entertainment for the Prince of Wales' first visit to Covent Garden. This short play is set in a realm called Kenna. As in Tickell's poem, there are fairies named "Milkah" and "Oriel", although in different roles, and changelings are important. (Interestingly, there were multiple plays written for this occasion, and I'm wondering if the playwrights were given a theme. Rev. Samuel Bishop wrote "The Fairy Benison," which also features Oberon, Titania and Puck celebrating the arrival of the Prince of Wales and blessing him. However, the managers preferred Hull's take on the subject, and that was the one that was presented before the royal family.) Since then, Tickell's poem has faded from the scene. It popped up now and then. A mention of the poem made it into Ebenezer Cobham Brewer's 1880 Reader's Handbook of Allusions. An 1881 book on the park was titled Kenna's Kingdom: a Ramble Through Kingly Kensington. Around 1900, there were a couple of resurgences of Kensington Gardens' fairy connections. First was The Little White Bird by J. M. Barrie, published in 1902. The story was Peter Pan's first foray into the public eye. In this early version, he was a week-old infant who escaped from his pram, learned to fly from the birds, and went to live with the fairies in Kensington Gardens. In 1903, as thanks for The Little White Bird's publicity, Barrie received a private key to Kensington Gardens, and in 1907, several chapters of the book were published on their own under the title Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens. As early as 1907, John Oxberry wrote in the magazine "Notes and Queries" that Barrie had "followed the example" of Tickell. There are certainly parallels. Both stories feature miniature fairies who live among the flowers in Kensington Gardens. In both stories, a human infant is parted from his family and comes to live among the fairies, taking on some of their nature in the process. There are some attractively similar lines; Tickell's colorful fairies resemble "a moving Tulip-bed" from afar, while Barrie's fairies "dress exactly like flowers" (although, in a reversal, they dislike tulips). British biographer Roger Lancelyn Green, however, emphasized that "there is no proof" and "there is no need to insist that Barrie had read Tickell's poem" (Green pp. 16-17). Miniature fairies clad in petals were generic ideas, everywhere in children's literature. As Green said, Barrie "could easily have arrived at the same conclusions without knowing of this earlier attempt to people Kensington Gardens with fairies." Barrie's strongest influence in using Kensington Gardens was probably that he lived nearby, and it was where he met the family who inspired him to write Peter Pan. Around the same time as Barrie, Tickell's poem got a second chance at popularity in the form of a sequel: the comic opera "A Princess of Kensington," by Basil Hood and Edward German. It debuted at the Savoy Theatre in London in 1903, and met with mixed success, running for only 115 performances. (Oddly enough, it undermines the original poem, with Kenna beginning the play by stating that she never really had feelings for poor deceased Albion and actually likes some other dude.) Kensington Gardens has embraced its fairy associations. A statue of Peter Pan was added to the gardens in 1912. In the 1920s, the Elfin Oak was installed. This was a centuries-old stump of wood, gradually decorated by the artist Ivor Innes with carvings and paintings of gnomes, elves, and pixies. With his wife Elsie, Innes produced a 1930 children's book titled The Elfin Oak of Kensington Gardens. Like their predecessors, the fairies of this book emerged by moonlight to dance and frolic. Was there a pre-Tickell association with fairies? Was there, as Lewis Spence wrote in 1948, "an old folk-belief" that "this locality was anciently a fairy haunt"? Although Tickell wrote in the poem that he had heard the story as a child from his nurse, Katharine Briggs expressed skepticism. He might well have heard fairy legends, and he certainly included some folklore in the poem, but "since he was born in Cumberland it is perhaps unlikely that his nurse had any traditional lore about Kensington Gardens" (The Fairies in Tradition and Literature, 183). Also note that Tickell was focused on some specific recent renovations to the garden, which wouldn't have had time to collect mythical status. In a book on the garden, Derek Hudson wrote that "Tickell seems to have been the first to establish a fairy mythology for Kensington" (p. 110). Despite all this, according to a writer in 1909, some people "have gravely taken... Kenna... as a real personage instead of a mere poetic myth." Tickell and Barrie both placed fairy kingdoms in Kensington Gardens. However, they did so for different reasons, and with different associations for fairies. For Tickell, the fairies were royalty. This was a long-standing English literary tradition. Spenser's Faerie Queene (1590) treated Queen Elizabeth as a fairy monarch, and Ben Jonson's 1611 masque Oberon, the Faery Prince depicted James I's son as Oberon. In 1767, when celebrating the Prince of Wales' first visit to Covent Garden, playwrights rushed to script plays in which Oberon and Titania welcomed him. The Fairy Favour, the one chosen for performance, actually greets the prince as the son of Oberon and Titania. That prince was King George IV. The same tradition continued with George IV's niece, Queen Victoria. The 1883 book Queen Victoria: Her Girlhood and Womanhood described the young princess in otherworldly terms: "Victoria might almost have been a fairy-princess, emerging from some enchanted dell in Windsor forest, or a water-nymph evoked from the Serpentine in Kensington Gardens" (emphasis added). Note that the Serpentine, a recreational lake, was added under the direction of Victoria's great great grandmother Queen Caroline. The royal family were described as fairies and gods in literature. The royal family lived in Kensington Palace. It was natural for Kensington Palace and its surrounding gardens, structured and developed under the royal family's direction, to be a fairy realm. As the 19th century progressed, this changed. In literature, Fairyland became more and more the domain of children. At the same time, Kensington Gardens became a public park and a place for children. Matthew Arnold's 1852 poem Lines Written in Kensington Gardens imagined the gardens as a forested realm for little ones, "breathed on by the rural Pan." James Douglas's 1916 essays, collected as Magic in Kensington Gardens, depicted the children at play in the gardens as "solemn little fairies weaving enchantments." Barrie's work is, of course, the gold standard, where Kensington is intertwined with fairies and eternal childhood. So far, Barrie's work seems more enduring than Tickell's. Although most people would probably associate Peter Pan's location with Neverland, the actual Kensington Gardens location now has references to Peter Pan such as the statue. Although both writers drew inspiration from the same location, officials embraced Barrie's work and made it part of the park's identity. SOURCES

In modern fantasy, the idea of the Seelie and Unseelie Courts - two opposing groups of the fae - has become popular. But where did this idea come from? What was the original inspiration? What do Seelie and Unseelie even mean?

Fae Divided into Sections First of all, there are various old references to different classes of fae which may oppose each other. The Dökkálfar ("Dark Elves") and Ljósálfar ("Light Elves") are contrasting beings in Norse mythology, with the first surviving mention from the thirteenth century. The Light Elves are fair and the Dark Elves are “blacker than pitch,” and the two groups are totally different in temperament. There are also the svartalfar (apparently the dwarves) but there’s disagreement over whether they are the same as the dokkalfar or not. 16th-century alchemist Paracelsus divided mythical creatures like Melusine, sirens, giants and pygmies into classes by the four elements (water, air, fire and earth). There was certainly a sense that there could be good or evil fairies. Reverend Thomas Jackson wrote in 1625, in A treatise concerning the original of unbelief, “Thus are Fayries, from difference of events ascribed to them, divided into good and bad, when as it is but one and the same malignant fiend that meddles in both; seeking sometimes to be feared, otherwhiles to be loued as God." Jackson took the stance that all fairies were equally evil tricks of Satan, but his argument still gives us a few crumbs of contemporary fairy beliefs. Hulden and unhulden were Germanic spirits and, beginning in the 15th century, also referred to the witches who consorted with them. The preacher Bertold of Regensburg (c. 1210-1272) exhorted the Bavarian people against belief in such things. There is also a Germanic goddess named Holda, although scholars have disagreed on which is older. The word may come from a German root meaning "gracious” or “kind.” There are also the huldra or huldrefolk from Scandinavian folklore, coming from a word meaning "hidden,” but for holden and unholden I lean towards the “kind” definition. So holden would be “the Kind Ones”, unholden “the Unkind Ones.” As far back as the 4th century, a Gothic translation of the Bible used the feminine word "unhulþons” for demons. This could possibly mean that "Unkind Ones" and hulþons as good counterparts were also around at the same time. I am not sure whether these “Kind Ones” were really kind, or whether this was a euphemism - but the presence of the very non-euphemistic "unholden" is telling. Both types were certainly demonized during Christianization. Bertold concluded that "totum sunt demones" (all are demons). In the 15th century, the singular character Holda began to appear among other denounced goddesses in the Diana/Herodias crowd. Centuries later, Jacob Grimm noted that witches' familiars might be "called gute holden [good holden] even when harmful magic is wrought with them”. Now let's look at the most famous example of contrasting fairy groups: the Seelie and Unseelie. The Seelie and Unseelie Courts The Seelie and Unseelie Courts are Scottish names for good and bad fairies. Seelie means blessed or lucky and ultimately comes from the Germanic "salig"; the same root gives us the German nature fairies called “Seligen Fräuleins.” "Seely wight" or "seely folk" was an old term for fairy beings, roughly equivalent to Good Neighbors or Fair Folk. Note that in this case, these names were not meant to be taken literally; they were names meant to appease the temperamental and dangerous fae. In one poem, a spirit warns a human against calling it an imp, elf or a fairy. "Good Neighbor" is an acceptable term, and "Seely Wight" is ideal: "But if you call me Seely Wight, I'll be your friend both day and night." In Lowland Scotland in the 16th century, some witchcraft and folk magic centered around the seely wights. Researcher Carlo Ginzburg argued that there were worldwide parallel traditions of folk healers who believed that they left their bodies to travel at night with friends and/or spirits. In these night journeys, they ensured a good harvest for their village by battling witches or even traveling to Hell. Usually these meetings took place on specific nights of the year. The most well-known are the Italian Benandanti (Good Walkers). Some of these cults were connected to fairies. The Sicilian "donas de fuera," or "ladies from outside," derived their name from the spirit beings they were believed to travel with. 13th-century bishop Bernard Gui instructed inquisitors to investigate mentions of night-traveling "fairy women, whom they call the good things [bonas res]." Not all groups had stories of protecting the harvest. Some, like the donas de fuera, were simply supposed to meet up and hang out on certain nights. Ginzburg's theory has met with some criticism, but it is true that going back into medieval times, Christian bishops spoke out against women supposedly meeting at night with a goddess named Herodias or Diana or a whole host of ladies. Christian authorities denounced this as superstition or hallucination. William Hay, around 1535, gave a specific Scottish example: "There are others who say that the fairies are demons, and deny having any dealings with them, and say that they hold meetings with a countless multitude of simple women whom they call in our tongue celly vichtys." Based on the few surviving pieces of evidence, history professor Julian Goodare constructed a theoretical cult: in the 16th century, a group of Scottish women (and possibly some men) believed that they rode on swallows at night to join the seely wights, a group of female nature spirits akin to fairies. Despite their name, these beings weren't necessarily good. In 1572, accused witch Janet Boyman blamed the "sillye wychtis" for "blasting" and killing a child. The main problem with the theory, Goodare admitted, is fragmentary evidence. Seely wights apparently disappeared from belief before the real furor of witch trials ever started. However, in the 17th century, “wight” continued to be a common generic Scottish term for mysterious and powerful spirits that were perhaps not exactly fairies, but something harder to define. One accused witch spoke of “guid wichtis,” another of “evill wichts.” (Despite the descriptors, in both cases these creatures were blamed for striking young children with illness.) Another accused witch, Stein Maltman, spoke of "wneardlie" (unearthly) wights. But although “wight” remained popular, “seelie” faded from view. The seelie wights were apparently gone. Or did they just get a name change? "Seelie" survived in fairy names like Sili go Dwt, Sili Ffrit, and the Seelie or Seely Court. One of the Seely Court's earliest known appearances is the Scottish ballad of "Allison Gross," collected in the Child Ballads. They ride on Halloween, and their queen releases a man from a witch's curse. The presence of a queen is what makes it a seely court, a structured government under a ruler. They are no longer just random wights. The queen's actions imply a benevolent nature. The Child Ballads also include "Tam Lin," which features a less friendly fairy queen. In some fragments and scraps, which weren't complete enough to put as full versions, the fairies are called the "seely court." "The night, the night is Halloween, Our seely court maun ride, Thro England and thro Ireland both, And a' the warld wide." Note that in this version, there isn't a tithe to Hell. Although the tithe is in the most popular variant, a few feature all the fairies visiting Hell, or (as seen here) riding all over the world. The idea of the fairies roaming on a specific feast night (Halloween or an equivalent) does hearken to the idea of Diana's procession, the donas de fuera, and other such groups. The fairy queen would be equivalent to the other patron goddesses. Another connection - in the 1580s, a poet named Robert Sempill wrote the satirical “Legend of the Bischop of St Androis Lyfe.” One section described the witch Alison Pearson as riding on certain nights to meet the sillie wychtis. In real life, Alison Pearson's testimony included a tale similar to "Tam Lin." Although the term "seelie wight" doesn't appear in the trial records, she said she had been taken away by the fairies and taught the healing arts, but had to escape, for a tenth of them went to Hell every year. So Pearson talked about fairies making a journey to Hell, and a contemporary writer identified her fairies as seely wights. So we have print mentions of "seelie" fairies going back to the 16th century. On the other hand, I don't know of any appearances by the "unseelie" until 1819, when the Edinburgh Magazine featured an article titled "On Good and Bad Fairies." It described the Gude Fairies/Seelie Court and the Wicked Wichts/Unseelie Court; the Unseelie, it specified, were the only ones who pay tithes to Hell. (However, it was still foolish to anger even the Seelie.) I am not sure what the writer's sources were, though they may have drawn on traditions familiar to them. Other early mentions of the Unseelie Court were quotes of this article. Overall, Seelie and Unseelie Courts as opposed groups of fairies – and the word “unseely” applied to fairies at all – did not appear in print until comparatively recent times. [Edit 7/5/21: The "unseelie" word does go back to the 1500s! Scottish poet William Dunbar (c.1460-1530) described Satan's "unsall menyie" or "unhallowed number," and "The flytting betwixt Montgomerie and Polwart" (1629) mentions an elf and and an ape begetting an "unsell" or "vnsell".] For a while, I've believed "unseelie" is a neologism. Calling the fairies Seelie was originally meant to avoid their wrath; why would you call a fairy Unseelie? That's death wish territory. But although this theory seemed clear-cut to me at first, it may not have been that simple. Evidence shows that people did refer to "evil" or "wicked" wights as well as seelie wights. But I do have one wild speculative theory. The idea of good and bad spirits goes back a long way. Holden and unholden from Germanic myth (potentially as far back as the 4th century) might be a similar word formation indicating good and evil spirits who somehow mirrored each other. Some of Ginzburg's ecstatic cults were supposed to fight opposing groups. The Benandanti, for instance, fought the Malandanti (Evil Walkers). Let's extrapolate on the theory; say the seelie wights or Seelie Court were once a witchcraft tradition similar to those cults. What if they sometimes didn't just "travel" across the world or to Hell, but actually battled an opponent at some point in their journey - or had some kind of encounter, perhaps involving a tithe? What if those opponents were Unseely Wights? William Hay spoke of the seely wights' followers distancing themselves from fairies and calling them demons. What if the unseely wights were the forces of Hell? There is way more to the spectrum of witchcraft beliefs throughout medieval times - much more than can be tackled in one blog post. Anyhow, Seelie and Unseelie have since become common descriptors in both folklore guides and popular fantasy works. The names are a way to delineate between good and evil fairies, and do have at least some background in Scottish folklore. Even in the oldest sources, though, the lines blur between whether any of these beings are "good" or "evil." Both seelie and evil wights were perilous. Sources

Other Blog Posts

In 1835, Hans Christian Andersen published his fairytale “Tommelise,” or Thumbelina. A childless woman seeks help from a witch and receives a barleycorn. When planted, it grows into "a big, beautiful flower that looked just like a tulip" with "beautiful red and yellow petals." When it opens: "It was a tulip, sure enough, but in the middle of it, on a little green cushion, sat a tiny girl."

In "Thumbelina," Andersen took loose inspiration from older thumbling tales, but the heroine's birth from a flower is unusual. Some thumblings are created from a bean or other small object, but most often he or she is apparently born in the normal way, through pregnancy. Why did Andersen choose to write Thumbelina born from a flower - and what is the tulip's significance? Flower Fairies There's a widespread motif of fairies living in flowers. Andersen would have been well-aware of this trope. Thumbelina later encounters flower-angels (blomstens engels). They are evidently not quite the same species (winged and clear like glass, and dwelling in white flowers), but Thumbelina is happy enough to settle down with them. Another Andersen story, "The Rose Elf" (1839) also deals with tiny flower-dwelling spirits. The tiny flower fairy became popular around 1600. Shakespeare was an important influence; A Midsummer Night's Dream elves creep into acorn-cups to hide, and The Tempest's Ariel sings of lying inside a cowslip bell. In the anonymous play The Maid's Metamorphosis, a fairy sings of "leaping upon flowers' toppes". In the 1621 prose version of Tom Thumb, Tom falls asleep "upon the toppe of a Red Rose new blowne." In the 1627 poem Nymphidia, Queen Mab finds a "fair cowslip-flower" is a "fitting bower." What about older versions of the flower fairy? Greek mythology included dryads and other nature spirits, including the anthousai, or flower nymphs. Before Shakespeare, fairies in legends were generally child-sized at smallest - there are exceptions, such as the portunes of Gervase of Tilbury. Fairies, witches and other spirits were often said to ride in eggshells or crawl through keyholes. Fairies were held to live in nature and dance in "fairy circles" made of mushrooms or grass, or were encountered beneath trees. I'm also reminded of a 6th-century story recorded by Pope Gregory the Great, where a woman eats a lettuce which turns out to contain a demon. The demon complains, "I was sitting there upon the lettice, and she came and did eat me." Superstitions held that demons might take up residence inside food if it wasn't properly blessed or protected with charms. Cowslips and foxgloves, already mentioned, were old fairy flowers. Cowslips are also known as fairy cups (Friend, Flower Lore), and foxgloves are fairy caps or as menyg ellyllon (goblin gloves). But these suggest very different scales. Flowers are hats and cups in language, but houses in literature. Katharine Briggs argued that Shakespeare did not originate the tiny flower fairy, but was inspired by contemporary tradition - however, there's not much evidence for this. Diane Purkiss took the exact opposite point of view, deeming it "questionable whether Shakespeare knew anything about fairies from oral sources at all," but I think this is an unnecessary leap. In more of a middle ground, Farah Karim-Cooper suggested that Shakespeare actually rescued fairies. In contemporary culture, they were being demonized, grouped with devils and witches and sorcery. Shakespeare made them benevolent but also tiny, therefore harmless and acceptable. In 1827, Blackwood's Magazine talked about Shakespeare's fairies and how they would "lodge in flower-cups, a hare-bell being a palace, a primrose a hall, an anemone a hut." I do not recall seeing these specific examples in Shakespeare, but this was now the popular perception. In the first 1828 edition of The Fairy Mythology, Thomas Keightley also talked about "the bells of flowers" as fairy habitations. "Oberon's Henchman; or the Legend of the Three Sisters," by M. G. Lewis (1803) describes fairies "Close hid in heather bells". In the poem “Song of the Fairies,” by Thomas Miller (1832), the fairies "sleep . . . in bright heath bells blue, From whence the bees their treasure drew," and then just in case we missed it, their "homes are hid in bells of flowers." Later in the same volume, a fairy named Violet "in a blue bell slept." Hartley Coleridge wrote of "Fays That sweetly nestle in the foxglove bells” (Poems, 1833) and Henry Gardner Adams had "The Elves that sleep in the Cowslip’s bell" (Flowers, 1844). The wood anemone was another fairy flower; at night the blossoms curled over like a tent, and "This was supposed to be the work of the fairies, who nestled inside the tent, and carefully pulled the curtains around them." (The Everyday Book of Natural History, 1866) This implies the existence of another explanatory legend. In a paper presented at a meeting of the New Jersey State Horticultural Society - yes - and published in 1881, the writer reminisced "I remember how I enjoyed the imaginary exploits of the little fairies that had their homes in these flowers. I had always thought it a pretty conceit to make the fairies live in flowers, but never thought how near the truth it is" . . . And then comes a leap to microorganisms. "A flower is a little universe with millions of inhabitants." Children's literature at the time was focused on edifying, providing morals, and providing scientific education. Fairy stories were considered a natural interest for children, and so they were often used to dress up school lessons, particularly on the natural world. They were a perfect way to launch into a lesson on insects or the world that could be found through a microscope. What about tulips specifically? David Lester Richardson's Flowers and Flower-Gardens (1855) mentions that "The Tulip is not endeared to us by many poetical associations." On the other hand, writing a century later, Katharine Briggs believed that the tulip was "a fairy flower according to folk tradition" and that it was a bad omen to cut or sell them. Taking a step back: in European thought, after the crash of the Dutch "tulip mania" in the 1630s, tulips generally became symbols of gaudiness and tastelessness, particularly in superficial female beauty - for instance, Abraham Cowley in 1656 writing "Thou Tulip, who thy stock in paint dost waste, Neither for Physick good, nor Smell, nor Taste." (Rees). As time passed, this faded into the background, but was not forgotten. David Lester Richardson wrote that tulips had remained extravagantly expensive, even in England, as late as 1836. There are a couple of 18th-century examples of tulip fairies. Thomas Tickell's poem "Kensington Garden" (1722) speaks of the fairies resembling a "moving Tulip-bed" and taking shelter in "a lofty Tulip's ample shade." In 1794, Thomas Blake's poem "Europe: A Prophecy" described a fairy seated "on a streak'd Tulip," singing of the pleasures of life. Intriguingly, in the same decade as Thumbelina, an early English folklorist named Anna Eliza Bray collected a story which also featured fairies within tulips. She recorded it in 1832 and published it in 1836, in A Description of the Part of Devonshire Bordering on the Tamar and the Tavy. The story follows an elderly gardener who discovers that the pixies have begun using her tulilps as cradles for her babies. She eventually dies. Her heirs rip up the flowerbed to plant parsley, but find that none of their vegetables will grow there. Meanwhile, the gardener's grave always mysteriously blooms with flowers. Bray does not give a specific source, other than to speak briefly of gathering the tales from village gossips and storytellers, with the assistance of her servant Mary Colling. Bray's pixie story was retold in fairytale collections and books of plant folklore. When she published a children's book, A Peep at the Pixies (1854), most of her focus in the introduction was on pixies’ small size relative to children; they could "creep through key-holes, and get into the bells of flowers." By the 20th century, the tulip as fairy flower was set. James Barrie wrote in The Little White Bird (1920) that white tulips are "fairy-cradles" (158), and Fifty Fairy Flower Legends by Caroline Silver June (1924), reveals that “Fairy cradles, fairy cradles, Are the Tulips red and white." Folklore In fact, fairies were not the only denizens of plants in legend. Birth from plants is very common in fairytales. English children were told that babies might be found in parsley beds, while in Germany, infants were more likely to be found among the cabbages or inside a hollow tree. (Curiosities of Indo-European Tradition and Folklore) In a French version, baby boys were found inside cabbages, baby girls inside roses. (e.g. Revue de Belgique, 1892, p. 227) Gooseberry bushes were also a likely spot. In Hindu culture and mythology, saying someone was born from a lotus was a way to indicate their purity. In Japanese stories, baby Momotaro is found inside a peach, and Princess Kaguya inside a bamboo. The Indian tale "Princess Aubergine" has a girl born from an eggplant. In the Kathāsaritsāgara (Ocean of the Streams of Stories), an 11th-century collection of Indian legends, Vinayavati is a heavenly maiden (divyā-kanyakā) who is born from the fruit of a jambu flower after a goddess in bee-form sheds a tear on it. In the Italian tale of "The Myrtle", from the Pentamerone (1634-1636), a woman gives birth to a sprig of myrtle. A fairy (fata) emerges from the plant each night, and a prince falls in love with her. However, the heroine is apparently of human scale, although she inhabits a plant not unlike a genie in a lamp. Later folklorist Italo Calvino collected more variants: "Rosemary" and "Apple Girl." The woman or fairy hidden within a luscious fruit appears in tale types such as "The Three Citrons." With the first known example of this story in The Pentamerone, there are probably as many variants of this story as there are types of fruit. In a close fairytale neighbor, a mother eats a flower to become pregnant - see the Norwegian "Tatterhood," the Danish "King Lindworm," and "Svend Tomling." "Tom Thumb" is usually cited as an influence on Thumbelina; in this story, a childless woman consults Merlin for help. Merlin prophesies her child's fate, she undergoes a very brief pregnancy, and then gives birth to a child one thumb tall. However, the two stories have little in common; the Thumbling tale type is widespread, and Andersen may have been inspired by other examples. The most likely candidate is "Svend Tomling," a chapbook written by Hans Holck and published in 1776. My translation is very choppy, but I think the gist is that a childless woman consults a witch. The witch causes two flowers to grow and instructs the woman to eat them. The woman then gives birth to Svend, one thumb high and already fully dressed and carrying a sword (beating out Tom Thumb, who has to wait several seconds for his wardrobe). I don't know for sure if Andersen knew this story, which hasn't achieved quite the same ubiquity as Tom Thumb. However, the fact that it was from his own country, and the similarities in Svend Tomling's and Tommelise's births, make a relationship seem likely. E. T. A. Hoffmann Fairytales weren't Andersen's only inspiration. One of his major influences was the fantasy/horror author E. T. A. Hoffmann (creator of The Nutcracker and the Mouse King, among other things). In Hoffmann’s “Princess Brambilla” (1820), a fairytale-esque subplot has the magician Hermod tasked with finding a new ruler for the kingdom. He causes a lotus to grow, and within its petals sleeps the baby Princess Mystilis. The person-inside-flower motif recurs throughout the story. Mystilis is later placed in the lotus to break a curse that has fallen on her, and emerges the second time as a giantess. Hermod himself is frequently seen seated inside a golden tulip. “Master Flea” (1822) has similar imagery. A scholar, studying a "beautiful lilac and yellow tulip," notices a speck inside the calyx. Under a magnifying glass, this speck turns out to be Princess Gamaheh, missing daughter of the Flower Queen, now microscopic and fast asleep in the pollen. Conclusion Andersen created his own thumbling tale inspired by folktales like that of Svend Tomling. However, he wove in plenty of elements in his own way - such as talking animals, or a girl born from a tulip. His work, including both "Thumbelina" and "The Rose-elf," shows the contemporary interest in fairies who lived inside flowers. Andersen's fairies in particular are most like personifications of plants. In the past, tulips had gained a bad reputation, becoming symbols of shallow frippery. However, by the time Andersen wrote, the disastrous tulip fad had had time to fade into history a little more. Instead, tulips started to be mentioned occasionally with fairies. In the 1800s, one author might have noted tales of tulip fairies as rare. However, a century later, Katharine Briggs could categorize it as a fairy flower. What changed? The most important thing may have been new associations for the tulip's shape; it was grouped in with other flowers that resembled bells or cups. I was startled when I went looking for examples of flower fairies - I occasionally found descriptions of them resting on top of the flowers, like Tom Thumb. However, more often than anything, I found the word "bell." Heather-bells, foxglove-bells, cowslip-bells, bluebells, bell-shaped flowers. In 1832, Thomas Miller's flower-fairy poem used the word bell three separate times. With fairies increasingly shrunken around Shakespeare's time, flowers that would have once been cups or hats were instead envisioned as houses or hiding places for fairies. The shape does suggest that something could be tucked inside, and lends itself to an air of mystery. Storytellers, including Andersen, focused on the idea of the hidden observer. Mary Botham Howitt wrote in 1852 "We could ourselves almost adopt the legend, and turning the leaves aside expect to meet the glance of tiny eyes." (George MacDonald used similar images, although with a more sinister slant, in his 1858 book Phantastes.) However, although Thumbelina's birth is still tied to the idea of flower fairies, it has more in common with tales of heroes born from plants. It is also strikingly reminiscent of E. T. A. Hoffmann's short stories; Hoffmann wrote twice of tiny princesses discovered inside flowers. In his work, tulips were not just gaudy or overly expensive, but had esoteric and mystical associations. His characters may be Thumbelina's clearest literary ancestors. Further Reading

"Don't thank the fairies"

Yet another thing that I see frequently in fantasy books and online discussion is that people should never thank fairies. It breaks fairy etiquette, or it places you in their power. But . . . where did this idea come from? Really, why shouldn't you thank a fairy? Two words: Yallery Brown. In her Dictionary of Fairies, Katharine Briggs made much of the idea of not thanking fairies as part of their etiquette. For instance, under good manners she wrote, "A polite tongue as well as an incurious eye is an important asset in any adventure among FAIRIES. There is one caution, however: certain fairies do not like to be thanked. It is against etiquette. No fault can be found with a bow or a curtsy, and all questions should be politely answered." I have previously mentioned how influential Briggs' work has been to modern fantasy. Briggs' evidence is the tale of Yallery Brown, originally published by M. C. Balfour in an 1891 article "Legends Of The Cars," in Folk-Lore vol. II. Joseph Jacobs wrote a version in plainer English. As the tale goes, a boy named Tom rescues a tiny old man the size of a baby, with brown skin and silky golden hair and beard. The grateful sprite tells Tom that he may call him "Yallery Brown," and promises him a reward - but warns Tom with a strange spark of anger never to thank him. From then on, Tom's chores do themselves, but the reward soon turns sour, as his fellow workmen find their own work ruined and turn against him, believing he's some kind of witch. Fired from his job, Tom tells the sprite "I'll thank thee to leave me alone." At those words, a cackling Yallery Brown curses him forever after to a life of bad luck and failure. Yallery Brown remains mysterious. He is clearly malevolent, with even his "blessing" truly a disguised curse, but it is never explained why thanking him is significant, or why it angers him enough that he will warn a human against doing so. Briggs drew the conclusion that explicit thanks were just not okay in fairy etiquette. Gratitude and appreciation are fine and dandy. Take, for instance, a man who mended a fairy's baking peel. The grateful fairies left him a cake. Eating it, he announced that it was "proper good" and bid "Goodnight" to the unseen fairies. He then "prospered ever after." Explicit thanks, though, is bad. For some reason. I’ve occasionally come across the theory that thanks is acknowledgement of debt, and it’s never a good idea to be indebted to the fae. Morgan Daimler's Fairies: A Guide to the Celtic Fair Folk is one example of a work that mentions this theory. This is a handy explanation, but does not explain Yallery Brown’s fierce opposition to being thanked. It’s true he is quick to repay a favor, supporting the idea he doesn’t want to be indebted to Tom. But still, why would he be angry about someone else owing him a debt? He seems pleased to have Tom within his power. Looking for analogues, we run into problems. The story of Yallery Brown is strangely unique. Usually, other fairies do not show the same repulsion to the words "thank you." For isntance, in the Swedish tale of "The Troll Labor," a troll paid a woman in silver, and "thanked her," although his specific words aren't given. Back to Yallery Brown and Balfour. Some doubt has been cast on the traditionality of Balfour's work. Balfour didn't just transcribe her tales, but gave them a literary flair. That, and the striking uniqueness of her stories, have drawn suspicion by later scholars. The English folktale collector Joseph Jacobs remarked that “One might almost suspect Mrs. Balfour of being the victim of a piece of invention on the part of her . . . informant. But the scrap of verse, especially in its original dialect, has such a folkish ring that it is probable he was only adapting a local legend to his own circumstances.” In the Dictionary, Briggs mentioned Balfour's stories multiple times, while also making reference to the controversy that by then had begun to swirl around Balfour's work. But this is aside from the point. Whatever the origin, Balfour's story is part of fairy mythology now. And I want to know why thanks are important in Balfour's story. Why is the term "thank you" offensive to Yallery Brown? Is there a missing piece here, a forgotten meaning? As I started looking for explanations, I realized that there's one line in the story that is usually missed, but which changes the entire outlook of the tale. Tom thanks Yallery Brown, with no ill consequences, at the beginning of the story! I only caught this on a second read. When Yallery Brown introduces himself and says that they will be friends, Tom responds "Thankee, master." Later, Tom tries to thank Yallery Brown again, this time for helping him with his work on the farm. This is when the sprite grows angry and commands that he never say those words. This changes the picture. Thanking Yallery Brown innocently for his friendship is fine. It is only thanks for work that angers him. Perhaps it is the low nature of farmwork. Perhaps it is the reversal of roles that upsets him; rather than a meek Tom who says "Thank you, Master," now Tom's message imply "Thank you, Servant." From here, there are connections to three other tale types. Closest is the famous tale of the household brownie. "Don't pay the fairies" Some classes of fairy work in human homes and help with chores. But their human hosts must be careful, for they will leave if given clothes or even the wrong sort of food. The safest bet is plain milk or porridge with butter. In the story of the Cauld Lad of Hylton, the servants behave as if clothes are a well-known way to banish unwanted spirits. Although leaving clothes is not a verbal thanks, it is an expression of gratitude that backfires. In The Elves and the Shoemaker, collected by the Brothers Grimm, the shoemaker's wife declares, "The little men have made us rich, and we really must show that we are grateful for it." (Emphasis mine.) She notices that the elves are naked and sews beautiful clothes for them. Unfortunately for her, the newly clad elves announce that they now look too fine and handsome to do manual labor, and the shoemaker loses their aid. In other cases, rather than the fae becoming too vain to serve, some find the gift infuriating. In a Lincolnshire version, a brownie gets angry that the offered shirt is made of rough hemp rather than fine linen. Alternately, the payment implied by the gift may insult the fae who have deigned to clean human homes. Or perhaps it's not an insult at all, just a signal that their term of service is over. The Highland spirit Brownie-Clod actually draws up a deal with some humans "to do their whole winter's threshing for them, on condition of getting in return an old coat and a Kilmarnock hood to which he had taken a fancy." However, his hosts put out his payment a little early, whether out of carelessness or because they're trying to be nice and forget that this is solely a business arrangement to him. Brownie-Clod takes the clothes and books it, leaving the rest of the work unfinished. (Keightley, Fairy Mythology, 396) The tale type is so widespread, with so many variations and rationalizations, that it's impossible to say what the true meaning is. Although some brownies seem gleeful, in other cases, like that of the phynnodderee, the spirit actually seems distraught that they must now leave. Lewis Spence theorized that the gift of clothes was insulting because the brownie was expecting a human sacrifice, and the clothes turned out to be only a decoy. I feel like that's a stretch. However, Gillian Edwards points out that these spirits are very frequently not just naked, but resemble hairy wild men or animals. (Hobgoblin and Sweet Puck, p. 111). The phynnodderee is a kind of satyr. Even Yallery Brown is covered in blond hair. The act of offering clothes might be read as an act of domestication. There's a patronizing feel to the actions of the shoemaker's wife, or farmer, or any human. They decide that the naked or hair-covered fae would be better off if they fit human social mores by wearing human-style clothes. Could there even be a connection to people turning their coats inside out to avoid being led astray by will o' the wisps, or protecting a baby from fairies by laying the father's clothes over the cradle? Whatever the roots of the story, the end result is always that a clumsy expression of human gratitude drives away fairy aid. "Don't interrupt the fairies" I have found one other tale type where the words "thank you" cause fairies to flee. In this story, a farmer discovers some tiny elves in his barn, threshing his wheat for him. "[T]he farmer, looking through the key-hole, saw two elves threshing lustily, now and then interrupting their work to say to each other, in the smallest falsetto voice: 'I tweat [sweat], you tweat?' The poor man, unable to contain his gratitude, incautiously thanked them through the key-hole; when the spirits, who love to work or play, 'unheard and unespied,' instantly vanished, and have never since visited that barn." (Choice Notes from Notes and Queries, 1859, p. 76) Similarly in Brand's Popular Antiquities, the farmer accidentally drives them off with the line that they've done "Quite enough! and thank ye!" Great! The fairies run away when someone thanks them. But wait - the act of thanks is not what they're running from. The storyteller in the first version explicitly states that they leave because they do not like to be watched. In addition, this is a very widespread story, and other versions are illuminating. A similar spying farmer does not thank the laboring fairies, but laughs at them with the condescending words "Well done, my little men." Again, the specific words that he uses are not the problem. The fairies leave because "fairies are offended if a mortal speaks to them." (The Folk-Lore Record, 1878) In most of the versions that I have read, there is no thanks. The farmer actually threatens the fairies, in a much more tense exchange. In “The Ungrateful Farmer" (Tales of the Dartmoor Pixies), the farmer is pleased that the pixies are doing his farmwork. He witnesses them throwing down their tools saying in exhaustion "I twit, you twit." He mistakenly believes that they have spotted him. Knowing that "once the pixies learn that they are overlooked they cease to return to that spot," he assumes they will leave, and leaps out at them bellowing angrily, "I'll twit 'ee!" Poof, no more pixies. In Thomas Keightley's Fairy Mythology, the farmer's anger is explained in a more straightforward way. The story is titled "The Fairy-Thieves" and the fairies are not helping with the harvest, but stealing it. When they make the declaration "I weat, you weat?", the farmer lunges at them with the words "The devil sweat ye. Let me get among ye!" In the more sinister story of "Master Meppom's Fatal Adventure," the "Pharisees" don't just vanish; they strike the farmer with their flails before disappearing, and he dies within the year. (Lower 1854) "Don't brag or boast of fairy gifts" Any misuse of fairy gifts could cost the receiver greatly, as in the story of the Fuwch Gyfeiliorn or stray cow. A man receives a fairy cow and his herds prosper, but as she grows older, he feels it's not worth keeping an elderly cow that will no longer give milk or calves. But when he tries to slaughter her for meat, she runs back to the fairy realm, taking all the herd with her. However, there was something in particular about revealing the fairy gift's origins. John Rhys, in Celtic Folklore: Welsh and Manx (1901), listed many versions of a tale where people are not to inform others where they got their fairy gold. For instance, a boy who was left money by the Tylwyth Teg every day, but only on the condition that he tell no one (pages 38, 83, 116, 203, 241). Generally, the tale concludes with the person telling their secret and losing the fairies' favor. The money never appears again. Occasionally, even the money they already had vanishes. In the 17th century, in Ben Johnson's Entertainment at Althorpe (1605), Queen Mab - bestowing a gift - announces, "Utter not, we you implore, Who did give it, nor wherefore: And whenever you restore Your self to us, you shall have more." The trope was around as early as the 12th-century lai of Sir Lanval, by Marie de France. In various versions from across the centuries, Lanval meets a fairy lady who becomes his lover and bestows him with wealth, gold and silver. She informs him that the more he spends, the more he shall have. However, if he ever reveals her existence, he will lose both her love and his fortune. This is more a taboo of secrecy: not to reveal the source to others. All the same, there is an overlap. It's a taboo against (public) thanks or acknowledgement. Conclusion The main theme of these tale families is that fairies like their gifts to be anonymous. They do appreciate gratitude, but they also want discretion, and they can be mysteriously picky.

If these taboos are crossed, fairy servants flee, fairy gifts melt away to nothing, and fairy sweethearts bid farewell. Not because someone used the words "thank you." That, on its own, doesn't insult the fairies' generosity. Instead, it's because a human barged in yelling at them, gave a hamhanded and offensive gift, terminated their contract, or betrayed their trust. The idea that the actual term "thank you" is offensive to fairies comes from "Yallery Brown," and nowhere else, so far as I know. The folkloric basis of Yallery Brown has been called into question, with later scholars wondering if the collector had the wool pulled over her eyes by her sources, or even if she went beyond polishing collected stories and into creating her own material. Maureen James wrote a thesis defending Balfour. At the same time, she acknowledged that many of the tales are found nowhere else. She suggested that rather than Balfour being wrong, there has been a lack of research into stories from the area of north Lincolnshire that Balfour examined. All the same, a close reading reveals that Yallery Brown does not find the words "thank you" offensive on their own. The words only become dangerous when the thanks is for his labor with farm work. Still mysterious, but it makes sense in the wider context of brownies, elves and fairies who hate to be loudly acknowledged, and who prefer subtler thanks. In fact, Yallery Brown might be a brownie. His name is Brown, after all. Edit 7/22/20: Important update! There may be more to the picture; Jacob Grimm, in Volume 4 of Teutonic Mythology, mentioned a German superstition that thanking a witch would place you in her power (p. 1800). SOURCES

Fairy dust: maybe it’s the stuff that sparkles from a fairy godmother’s magic wand. Or maybe fairies just naturally exude it. (Or, if you delve into Disney’s expanded Tinker Bell universe, fairies need it to fly and it is a vital resource for which the characters must occasionally go on perilous quests.) Alternately, in craft stores I’ve come across little bottles of glitter labeled “fairy dust” to be used in a fairy garden. But where did the idea of fairy dust come from? I went looking for older sources which mentioned fairies in connection with dust. Some are fairly mundane. The fairies in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, like helpful household brownies, “sweep the dust behind the door.” Okay, so that’s not really their dust. In reverse, according to Thomas Keightley, the German kobold “brings chips and saw-dust into the house, and throws dirt into the milk vessels.” Closer is John Rhys' Celtic Folklore: Welsh and Manx, where he tells of a fisherman named William Ellis who - out on a dark misty day - saw a large crowd of little people about a foot tall, all dancing and making music. Entranced, he watched for hours, but when he approached too close, "they threw a kind of dust into his eyes, and, while he was wiping it away, the little family took the opportunity of betaking themselves somewhere out of his sight, so that he neither saw nor heard anything more of them." Similar, though it doesn't feature dust per se, is the tale of Yallery Brown. There, the titular elf blows a dandelion puff into a boy's eyes and ears. "Soon as Tom could see again the tiddy [tiny] creature was gone." George Sand's short story "La fee poussiere" was translated as "The Fairy Dust" in 1891. "Fairy Dust" in this case is the name of a character, a fairylike being who oversees everything from the earth itself to tiny particles of dust. The main character encounters her in a dream. In Félicité de Choiseul-Meuse's 1820 fairytale "The Marble Princess," a fairy godmother gives a prince "gold dust of the purest quality" to blind serpents so that he can fight them. "What Mr. Maguire Saw in the Kitchen," an 1862 story, a character waking from a disorienting dream refers to "dust . . . fairy dust that took away my five senses to the other world, and put me beyond myself." (Dialect removed.) Mary Augusta Ward's Milly and Olly: or, A Holiday Among the Mountains (1881) features a mention of a fairy throwing golden "fairy-dust" into a girl's eyes so that she sees the beauty in a certain place. There are no literal fairies in the book, but the description is significant. So far, two tales feature dreams, two have dust used to physically blind others, and the last has dust which alters someone's perception of the world. Why this connection between fairies and dust in the first place? An interesting link might lie with mushrooms. Many varieties are named for the fairies, and they have traditionally been associated with fairies in a number of ways, possibly in part because of some toadstools' hallucinogenic properties. One particular fungi tied to fairies is the puffball, a mushroom full of brown dust-like spores that are released when it bursts. Other names include "puckball," “puckfist,” “pixie-puff” or “devil’s snuffbox." (In this case, "fist" does not mean a closed hand, but a fart or foul odor. So these mushrooms were the Devil’s/Puck’s/Fairy’s farts.) In Scotland they were known as Blind Man’s Ball or Blind Man’s Een (eyes). John Jamieson suggested in 1808 that this was due to a belief that the spores caused blindness. However, it’s also possible that they were named for their resemblance to eyeballs. The mushroom connection is fun, but European puffball mushrooms are evidently not hallucinogenic. Another possible plant association: pollen, which can look like golden (yellow) dust, and which would have become a stronger link as the modern flower fairy gained popularity. The Victorian educational children's book, Fairy Know-a-Bit, or, A Nutshell of Knowledge (1866) declares that fairies refer to pollen as "gold-dust" and love "to sprinkle [it] over each other in sport."

There is another very old tie between fairies and dust. Traditionally, fairies were believed to be present in the dust clouds stirred up by the wind on the road. Any humans on the road should beware, and show respect to the otherworldly travelers. The cloud of dust might even contain kidnapped humans who were carried along with the fairies. It's been suggested that the Rumpelstiltskin-like character Whuppity Stoorie has a name meaning whipped-up dust, or stoor. For a similar concept, think of the term "dust devil" for a whirlwind. This idea may be tracked back to the 17th century at least. In 1662, accused witch Isobel Gowdie pulled from fairy lore for her confession. She described how witches, like fairies, would use tiny grass stalks as horses to "fly away, where we would, even as straws fly upon a highway" – in a whirlwind of bits of straw above the road. She added that "If anyone sees these straws in a whirlwind, and do not bless themselves, we may shoot them dead at our pleasure. Any that are shot by us... will fly as our horses, as small as straws." There's also a touch of the idea of perception here. Humans perceive only a cloud of dust, but those "in the know" realize that fairies are traveling unseen. In Teutonic Mythology vol. 3, Jacob Grimm makes a reference to witches' or devil's ashes being strewn to raise storms, and Richilde (enemy of Robert the Frisian) throwing dust in the air with "formulas of imprecation" to destroy her enemies. One more traditional connection between fairies and dust is quite sinister. In many stories, when a human returns from Fairyland, they do so without realizing that they’ve unwittingly spent centuries away from our world. King Herla, for instance, gets a nasty shock when some of his friends dismount from their horses only to crumble into dust the second their feet touch the ground. However, the key to modern fairy dust is the story of the Sandman. In European folklore, every night a mythical being sprinkles sand or dust into children’s eyes to send them to sleep and give them dreams. The sand/dust may be a way to explain the “sleep” or gritty discharge left in someone’s eyes when they wake up in the morning. E. T. A. Hoffmann’s 1816 short story Der Sandmann features a sinister Sandman who steals children’s eyes after throwing sand at them. Hans Christian Andersen’s 1841 tale "Ole Lukøje" ("Mr. Shut-eye") has a gentle sleep-bringer who sprinkles “sweet milk” into children’s eyes. However, subsequent translations changed this to “powder” or “dust" as the character was gradually merged with the Sandman. There was overlap with the fairy world, and this would only increase. A 1915 dictionary defined the Sandman as "a household elf.” The children's play “Bluebell in Fairyland,” first produced in 1901, was one of the inspirations for Peter Pan. The main character's travel to Fairyland is framed as a dream. Per John Kruse's site British Fairies, the play mentions the "dustman" (Sandman) and features golden dust being strewn as the characters fall asleep and enter Fairyland. Unfortunately, the play's script and lyrics are not currently available where I can access them. Algernon Blackwood's 1913 book A Prisoner of Fairyland may also have been influenced by Bluebell. It features a “Dustman” who sprinkles golden dust “fine as star-dust” into people’s eyes to cause them to sleep. Again: sleep, dreams and fairyland are interconnected. But it was J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan (play published 1904, novel published 1911) which really popularized the modern view of fairy dust. From the moment Peter Pan first physically appears in the novel, he is accompanied by fairy dust: “the window was blown open by the breathing of the little stars, and Peter dropped in. He had carried Tinker Bell part of the way, and his hand was still messy with the fairy dust.” The dust which Tinker Bell exudes bestows children with the ability to fly, and to travel to Neverland, which is made up of their own imaginative stories and daydreams. The island is first described in a sequence where the Darlings' mother examines her sleeping children's minds. When the children reach the island, they find all the locations and characters they've dreamed up. At one point Peter Pan speaks to "all who might be dreaming of the Neverland, and who were therefore nearer to him than you think." Disney’s animated adaptation came out in 1953. They altered it a little, calling the stuff “pixie dust.” Tinker Bell became an instant mascot, and her pixie dust was a callword for Disney. (They use "pixie" and "fairy" interchangeably to refer to the character, which is a post for another time.) Neverland's status as both fairyland and dreamworld is toned down in the film version, but still hinted at. The Darling children meet Peter Pan when he wakes them in the middle of the night, and - unlike the book - after they return, their parents enter the room only to find them fast asleep, as if they never left. Disney's ubiquitous Peter Pan helped popularize the modern idea of fairy dust as glittering stuff given off by fairies or pixies. It was also an important step in leaving behind the associations with dreams and, thus, the Sandman. Associations between fairies and dust are very old, seen in the whirlwind transportation and in puffball mushrooms. By the 1800s, we have mentions in literature tying fairy dust to vision, eyesight, dreams, and perception of reality. Ultimately fairies and the Sandman were equated, as were Fairyland and Dreamland. At this point, they've diverged. However, I am reminded of the 2012 animated film Rise of the Guardians, where the Sandman works with glowing golden sand that looks a lot like Disney Tinker Bell's pixie dust. Also, "fairy dust" and similarly "angel dust" are slang terms for drugs, keeping that idea of a change in perception. References and Further Reading

Recently, when reading fantasy, I keep running into the idea that fairies cannot lie, only tell the truth. For this reason, they must use tricky language – literal truths disguising real meanings. For example, in Holly Black's novel Ironside, a fairy says that when she tries to lie, "I feel panicked and my mind starts racing, looking for a safe way to say it. I feel like I'm suffocating. My jaw just locks. I can't make any sound come out" (p. 56).